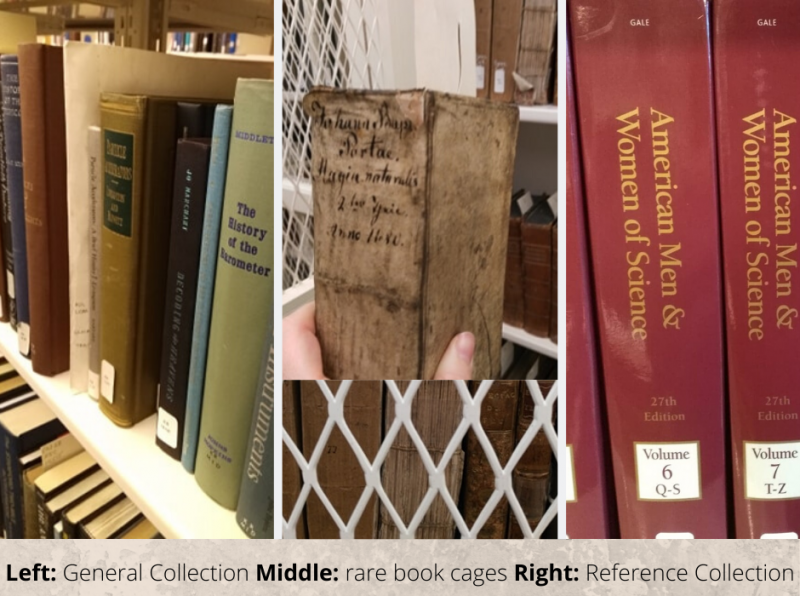

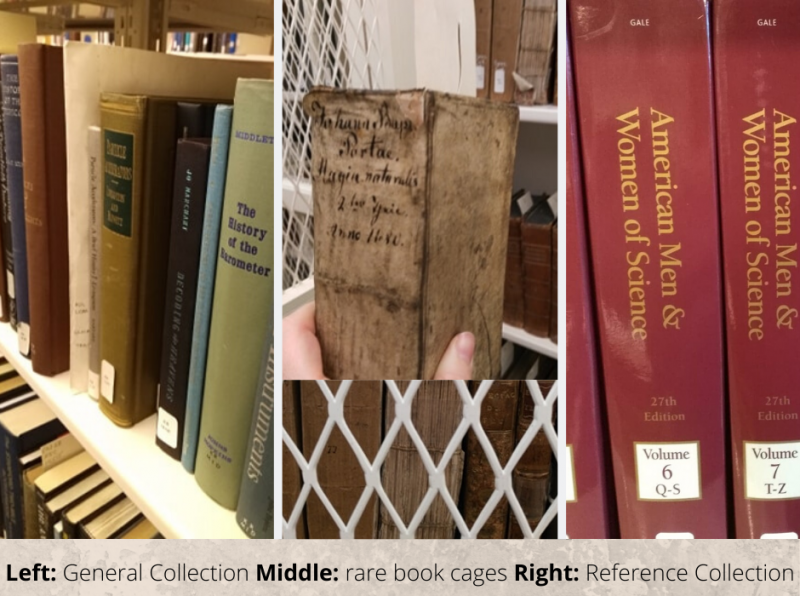

Left: General Collection, Middle: rare book cages, Right: Reference Collection

Quote from John Carter’s ABC for Book Collectors.

Aaron Auyeung.

Here at the Niels Bohr Library & Archives (NBLA), as in many institutions, we have our own definition of what makes a book “rare” or designated for our special collections. When we add a book to our collection, we have three book collection types to choose from:

Left: General Collection, Middle: rare book cages, Right: Reference Collection

It’s worth noting that the general collection and reference collection are open stacks, which means they are on bookshelves that are fully browsable by the public, while the special collections are closed stacks that are secured and not browsable by the public. However, anyone can read a special collections book: simply request for a member of the staff to retrieve the book.

But! What makes a book special enough to be a rare book? While this might seem like a straight-forward question, I turned to the pages of our trusty volume of ABC for Book Collectors (find ABC’s full definition of rarity here

ABC: In an unusually succinct section of the somewhat flowery prose of ABC, there are only three lines in Carter’s long definition of rarity specifically devoted to monetary value. The gist of the section is that there is folly in “assuming that all rare books must be expensive and vice versa.”

NBLA: We don’t have an official stance on monetary value, but generally, we put valuable books into special collections. However, if a book is inexpensive, but is both scarce and prominent, we would consider putting it into special collections. Although we cannot legally supply monetary appraisals to book donors, we do perform internal appraisals of our books for insurance purposes. In general, we are more focused on the research and historic value of our collections rather than their monetary value.

Caitlin Shaffer joined the NBLA team in fall 2019 and is helping us prepare to move our pre-1920s books from our general collection into special collections. Here she is holding a rather marvelous book that was in our open stacks and is now destined for special collections: Wonders of Electricity by Jean Baptiste Baille.

ABC: Age - particularly old age - is something I would consider to be one of the common stereotypes of a defining factor in what makes a book rare. However, Carter does not discuss age in his definition of rarity. Some of the examples ABC uses as books that are generally accepted to be “rare books” - the Gutenberg Bible (15th century) and the First Folio of Shakespeare (17th century) are certainly old.

NBLA: Until recently, age was not a defined factor for our library in the decision to put an item into Special Collections. Though grown haphazardly, factors like scarcity and prominence informed the inclusion of most books currently in our Special Collections at the time of writing (May 2020), and the majority of these happen to be published before 1900, but it was not an official policy to put a book into Special Collections solely because of its age. However, in late 2019, we began a long-term project to have a more thoughtful and comprehensive plan about what books belong in Special Collections, and created a cut-off date of 1919. With this designation, all books that are 100 years old or older will be in Special Collections, but more significantly, according to the American Institute of Physics’s resident historian Greg Good, “1919 is the end of the long 19th century and the beginning of the modern era that follows. Classical physics wanes and modern physics begins in this period.” As NBLA is a history of physics library, this is an important consideration. We are not alone in having a year cutoff point: the National Library of Medicine in Washington, D.C. catalogs its books published before 1914 in its rare books collection

ABC: Carter gives definitions of four kinds of rarity that have to do with the scarcity of the item:

“(1) Absolute Rarity. A property possessed by any book printed in a very small edition; of which therefore the total number of copies which could possibly survive is definitely known to be very small. For instance, of Horace Walpole’s Hieroglyphic Tales [1785] seven copies were printed, six of Tennyson’s The Lover’s Tale [1833], and of Robert Frost’s Twilight [1894] only two.

(2) Relative Rarity. A property only indirectly connected with the number of copies printed. It is based on the number which survive, its practical index is the frequency of occurrence in the market, and its interest is the relation of this frequency to public demand.

(3) Temporary Rarity. This is due either to an inadequate supply of copies in the market of a book only recently begun to be collected, or to a temporary shortage of copies of an established favourite.

(4) Localised Rarity. This applies to books sought for outside the area of their original circulation or later popularity with collectors.”

Front cover of Why Einstein Was an Ignorant Fool by John Carter, 2018, from NBLA’s general collection.

NBLA:

Of the four definitions of rarity above, NBLA is most concerned with relative rarity. One place we look to determine the relative rarity of an item is worldcat.org, a union catalog that shows holdings of all of its 17,900 participating libraries, of which NBLA is one.

In this example,

We do have some books that are relatively rare, but are in our general collection rather than rare books. These tend to be self-published books from the past decade and some of these are the work of fringe theorists, such as James Carter’s Why Einstein Was an Ignorant Fool. While there might not be many copies of these out there and we want such books in our collection for research purposes, categorizing a book into rare books gives it a certain import that we want to assign judiciously. However, we re-evaluate our collections periodically, and there is always the possibility that a librarian next decade or next century will decide to categorize such volumes as rare books.

ABC: “The definition of ‘a rare book’ is a favourite parlour game among bibliophiles. Paul Angle’s ‘important, desirable and hard to get’ has been often and deservedly quoted: Robert H. Taylor’s impromptu, ‘a book I want badly and can’t find’, is here quoted for the first time.”

Pierre-Simon LaPlace’s Exposition du systême du monde with beautifully marbled endpapers, second edition, 1799, from NBLA’s rare book collection. For more information about this book, check out Sally Newcomb’s article on it here.

Aaron Auyeung

ABC also quotes Encyclopedia Britannica’s definition of rarity by A. W. Pollard, who remarks, “This qualification of rarity [in the sense of being difficult to procure], which figures much too largely in the popular view of book-collecting, is entirely subordinate to that of interest, for the rarity of a book devoid of interest is a matter of no concern.”

NBLA: This begs the question: what is our definition of a desirable and interesting book? For us, it will have to have some relevance to the history of physics and to our existing collections. On occasion, we might find a book that we would collect because we have obligations to our parent institution, the American Institute of Physics, since we are also an institutional repository. We have a collection development policy, written by colleague Allison Rein, with more details that helps to guide these acquisition decisions. From the policy:

“The Niels Bohr Library collects, catalogs, preserves, and makes accessible publications in the history of physics, astronomy, geophysics and allied fields. The Library supports the efforts of the scholarly community to document, investigate, and understand the nature and origin of developments in the physical sciences and their impact on society.”

So, as much as we might like to purchase rare first editions of fantasy novels published in the 20th century on a personal level, this would not fit our collection. The good news is that those books probably fit into a different library’s collection development policy. Happily, some science fiction does fit with our collection, much to the delight of certain NBLA librarians, including works of Isaac Newton, who famously wrote both science fiction (androids! space travel!) and physics texts.

Zeitschrift für wissenschaftliche Photographie und Photochemie, vol. 5, 1907, from NBLA’s rare books collection. As this was printed in the early 20th century, we will expect the paper to degrade more quickly than our 1799 copy of Laplace’s Exposition du système du monde, pictured above.

Nathan Cromer

Condition

ABC: Since ABC is geared toward booksellers, the condition or “fine-ness” of the book is considered important. “The degrees of rarity attributed to books are expressed in a wide range of terms, mostly self-explanatory…. They may be related to the book’s condition; eg. ‘very rare in boards’, or ‘uncommonly found in fine state’, or ‘almost all known copies are badly browned’.”

NBLA: When it comes to our special collections, we have and will keep books in less than fine condition - pages falling out, discoloration, spine falling off, you name it. Especially when it comes to rare books, we never know when another copy of the book will be available for purchase, so we do everything we can to hold onto the one that we have. Rare book sales work differently from your typical modern book sales: there is usually one copy of a book advertised in a catalog or at an auction, and when it’s gone, there might be nothing like it on the market for years. Generally, if a book is in a state of badly needing intricate repairs and an institution has the budget for and need for it, libraries and book dealers will often either send books to professional conservators for treatment or have conservators on staff.

Preservation is important to us, as to most special collections libraries. All of our collections are housed in temperature and humidity controlled environments. We stabilize our special collections books with the appropriate housing, such as acid-free four-flap enclosures, and make a note of the condition in the book’s catalog record so that anyone looking to handle the book will be prepared to be extra careful. We also have pest management programs to keep away any rodents or insects looking for a paper-flavored snack, and we have disaster response plans in place to deal with building events like leaks or fires that might be destructive to our collections.

All of this being said, generally, older books tend to keep better and longer than newer books because of the quality of materials used in books published before circa 1850: paper was more durable because it was made from cloth rags rather than wood pulp, and bindings were always sewn rather than glued, and a sewn binding is far more stable over time than a glued binding.

Other sources

As this National Park Service publication

For another perspective, I asked Colleen Barrett, rare books librarian at the University of Kentucky Libraries, what makes a book rare to her. This is her answer:

“I think it changes from institution to institution depending on what their specialties are, but for me the rare books are the ones that I would run for first in a fire because their loss would be of a greater significance to the cultural record at large. There are of course also the somewhat agreed upon ‘high spots’ in any collecting field that have been determined by other collectors, lists of important works, and the market (that are hopefully also useful teaching tools for students or research), but they don’t necessarily correlate to dates or scarcity in any predictable pattern that makes sense.

For example, there are something like 50 copies of the Gutenberg Bible still in existence, so even though it is quite valuable it’s not actually all that rare. If I could only grab our leaf of that or an early Kentucky imprint in one copy from our stacks I would definitely go for the imprint, even if no one had ever heard of it because that loss would be of longer lasting significance to the Commonwealth. Of course I also have both of them housed in the rare books area as I would like both of them to be priority for remediation if a water leak happens or another disaster.

Also just because something is the only copy left in existence it doesn’t automatically make it valuable. There are plenty of monetarily worthless computer manuals that are now rare because everyone threw them away, but they are still not valuable on the market because people are unwilling to buy them.** I don’t have a rubric for this because I haven’t sat down long enough to generate one, but in our stacks a book gets classified as a rare book if replacing it would be next to impossible from a monetary, scarcity, or provenance standpoint. There are no official cut offs, but that’s where we’re currently at since the collection is small enough that I can physically handle each one as part of the inventory process to evaluate them.”

Finally, some wise, if strongly phrased, parting words from ABC:

Quote from ABC for Book Collectors. Book in background is Saggi di Naturali, by Accademia del Cimento, published 1610. From NBLA’s rare books collection.

Nathan Cromer

* Book in background of the image at the top of this post is Robert Boyle’s New Experiments and Observations on Touching Cold, 1665, from the Niels Bohr Library & Archive’s rare books collection. For more on bibliomania, check out our post “The ABCs of Ex Libris Universum.”

** The right library might find old computer manuals to be valuable for their collection - it all depends on their collection development policy.

Subscribe to Ex Libris Universum

Catch up with the latest from AIP History and the Niels Bohr Library & Archives.

One email per month