Jacqueline Mitton and Simon Mitton.

stillvision.co.uk

With great pleasure, we welcome Dr. Jacqueline Mitton to Ex Libris Universum to talk about her new book on Vera Rubin, co-written with Dr. Simon Mitton. Vera Rubin: A Life

What drew you to write about Vera Rubin?

Jacqueline Mitton and Simon Mitton.

stillvision.co.uk

I’ve been interested in the lives of women astronomers for a long time, not least because I am one! Several decades ago, I was invited to give a talk on the subject to a group of women students in Cambridge. At the time I knew very little, but my research for that talk sparked my life-long enthusiasm for making the struggles and achievements of female astronomers more widely known and appreciated. One of my regular talks has had the title (which I admit I borrowed rather than invented) “A woman’s place is in the dome”.

In 2017, my husband Simon and I heard that Harvard University Press was interested in commissioning a biography of Vera Rubin, who had died in December 2016. We knew something about her important work on galaxies and how it had persuaded many astronomers that dark matter exists in abundance in the universe. And we knew that she was held in high regard, not just for her research but as an outspoken advocate for women scientists. Simon is also an enthusiast for promoting women in astronomy. He had written one biography already – of the British cosmologist Fred Hoyle – and took great satisfaction from doing it. So, the opportunity to research Rubin’s life and become her first biographers was for both of us irresistible.

How did you work together as co-authors?

We had worked on books together before, so we knew that collaborating on such a project would be a shared experience we would both enjoy. Fortunately, our writing styles are not dissimilar, and with years of experience, we are both quite professional in our approach to book-writing. We have never argued about it!

When the opportunity came along to make a proposal for the Rubin biography, Simon was already committed to another major book project that was clearly going to take up much of his time for a year or two. So we decided to split the work unequally. I would do the bulk of the writing, and would also obtain the illustrations and the permissions, prepare the index, track and collate the revisions to the text – and all the other time-consuming elements that go into completing a book. Simon would contribute the three chapters based primarily on Rubin’s important published research and act as ‘consultant’ for the overall project, drawing on his previous experience of writing a biography.

It all went well. Both of us revisited the whole text numerous times, polishing and correcting, commenting on each others’ chapters and incorporating suggestions from our editors and peer reviewers. And we enjoyed it every bit as much as we had hoped.

What materials did you use from the Niels Bohr Library & Archives and how did they shape the book?

I was surprised when I counted that we had cited 12 online oral history transcripts from the Niels Bohr Library & Archives. Four of them were interviews with Rubin – three conducted by David DeVorkin (1995

There is an interesting story attached to the 2007 interview. When we first started our research, it wasn’t on the AIP web site. David DeVorkin gave us an unofficial transcript with strict instructions not to cite or reference it because it had not been formally approved. It was 2018. Eleven years had elapsed, and this important resource was in danger of being forgotten. We were in touch with the Rubin family so I asked if they could approve it, which they did. Then, I’m not sure exactly what happened behind the scenes, but the transcript made it onto the web site in time for us to be able to cite it in the book. And I’m delighted that other researchers now have access to it.

Other interviews that helped us with the research were those with Geoffrey Burbidge

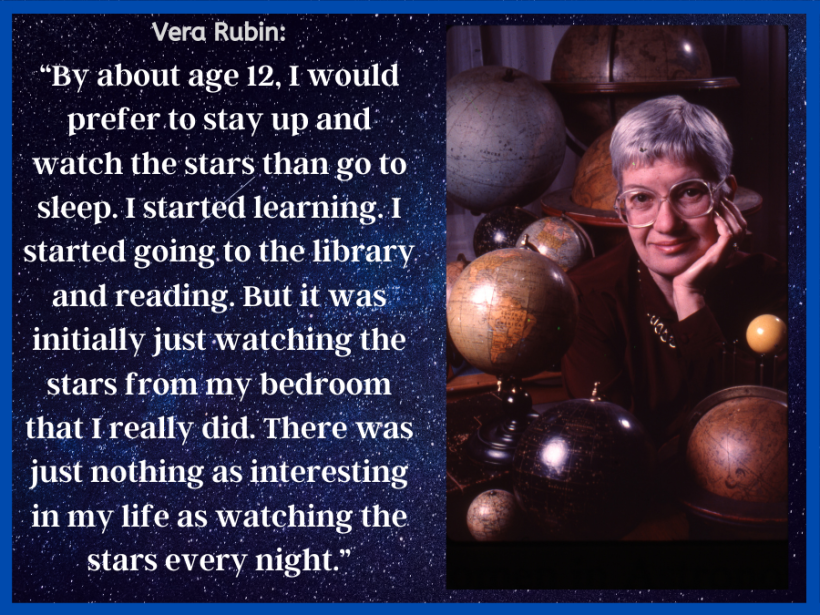

Quote from Vera Rubin’s oral history interview with Alan Lightman, 1989, cited in Vera Rubin: A Life.

Rubin Vera A2, Photograph by Mark Godfrey, courtesy of AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Gift of Vera Rubin

Book cover design by Graciela Galup, art courtesy Carnegie Institution for Science, Department of Terrestrial Magnetism Archives. Photograph by ARAX Photo Studio, Poughkeepsie, NY

Where else did you do research for the book?

Chief among our other major sources were the Vera C. Rubin Papers

We made two trips to Washington to work in the Library of Congress. Shortly before the first visit, we learned that Rubin’s papers were still being processed: they were not yet open for public access – something that had never occurred to us! We had a brief period of panic. However, the archivist working on the collection was wonderfully helpful. We were allowed to see the half of the collection that she had already processed and we met with her several times.

The Carnegie Institution’s Department of Terrestrial Magnetism (now part of the Earth and Planets Laboratory), where Rubin worked for 50 years, was another place of pilgrimage. They hold a comprehensive Vera C. Rubin photographic collection

We found more interview transcripts online, and in the LoC. Toward the end of her life Rubin also published an autobiographical article, but lastly we would like to mention the marvellous recordings of Rubin’s father recalling his eventful life, made available to us by the Rubin family. An engaging raconteur, he told the full story of how his family fled from the persecution of Jewish people in eastern Europe when he was seven years old, and how he built his life and brought up his family in the United States. A whole other book there possibly!

What did you learn about Rubin that was surprising or new to you?

The discovery that probably surprised us most was in the Library of Congress papers, where we found a huge collection of personal letters and cards to Rubin from another astronomer, Father Martin McCarthy SJ, of the Vatican Observatory, Rome. Most are in small handwriting, some crammed onto airmail sheets. Although it is clear from the contents that Rubin’s side of the correspondence was equally prolific, sadly it has not survived.

Rubin first met McCarthy when he visited Georgetown University. Their professional friendship that ensued survived for over thirty years. McCarthy’s letters – often lengthy – range widely over matters of common astronomical interest, their families, travel, political events and his life as a priest. It’s clear that Rubin regarded McCarthy, who was slightly older than her, as a professional mentor at first then later as a person outside the family with whom she could discuss personal matters freely. No-one other than her husband knew and understood Rubin better than McCarthy. Perhaps it is not surprising that she never discussed this supportive but very private friendship in any interview.

We felt privileged to be the first researchers to read these personal letters, and all the other correspondence and notes from Rubin’s files, many of which she herself would not have read for decades and had probably long since forgotten.

-Q&A organized by Corinne Mona, Assistant Librarian

Subscribe to Ex Libris Universum

Catch up with the latest from AIP History and the Niels Bohr Library & Archives.

One email per month