Last month, physicist Richard Garwin died at the age of 97. His scientific work spanned a wide array of fields and topics, including crucial contributions to the design of the first hydrogen bomb. He spent most of his career at IBM and was a prolific consultant and adviser to the US government, serving on the President’s Science Advisory Committee and the JASON advisory group. Garwin left behind an extraordinarily large and rich archive

AIP historian Anna Doel interviewed Melanie Rinehart and Kathryn Antonelli, the manuscript and digital archivists at APS responsible for processing the Garwin papers, by email. The exchange has been lightly edited for length and style.

Anna Doel: How and when did the Garwin papers come to APS, and in what condition and level of organization? Were there any conditions or restrictions to their processing or use?

Melanie Rinehart, manuscript archivist: The Richard Garwin papers came to the APS from two sources: the IBM archives (at Garwin’s request) and Garwin himself. We had several accessions from 2013 to 2021. As an APS member since 1979, Garwin knew we would be the ideal repository for his archives. The material from the IBM archives included correspondence, transcripts, research materials, prints and publications, conference materials, etc., from 1952 through 2010; basically anything that had gone through his office there. Everything was in great shape and very well organized. Garwin was kind enough to write context sheets for many materials with background information, which were invaluable to me as the archivist and will be very interesting for researchers!

Doel: Is there anything special about them?

Rinehart: The breadth of this collection is incredible—it measures 219 linear feet. The correspondence series is 107 linear feet, and even that only covers physical correspondence from 1984 to 2010. Most archival collections at APS aren’t even half that size. There’s even more in the microfiche series, which has correspondence from the start of Garwin’s IBM career in 1952 until the early 1980s. And that’s just in the physical half of the collection, for one type of material! There’s a robust email archive as well, along with digital files.

There’s something for almost every kind of researcher of twentieth-century science and politics: Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative, anti-nuclear proliferation, touchscreen development, supersonic transport, relations with Chinese scientists starting in the 1970s, even cold fusion (Garwin was a member of the Department of Energy committee that investigated Fleischmann and Pons’s claims). One of the most unique items is a rare 1974 ARPANET communication among JASON members.

Doel: What kinds of media did they consist of? How do different media live together in an archive collection?

Rinehart: This collection includes audio and visual tape and disk recordings of talks, media appearances, radio interviews, lectures, workshops, and debates that Garwin participated in. We also have photographic slides taken by Garwin’s father, Robert.

When it comes to storage, there are specially sized boxes for storing items like cassette tapes, which I used; the videotapes just went into a standard Hollinger box. The slides are in acid-free banker’s boxes as they came in their own labeled slide magazines. Because everything had been stored in good conditions, I just had to rehouse it to fit on our shelves to live next to the manuscripts.

Doel: What was your approach as a manuscript archivist to working with the Garwin papers? What kinds of research did you do? What were the challenges and how did you work through them?

Rinehart: As with every collection I process, I started by reading the legal file, and then expanded to an internet search for a basic background—AIP’s oral histories were incredibly helpful. Then I opened up every single box of unprocessed material sitting on the shelf in order to create an inventory. Each of the 183 boxes had a numbered Post-it note attached so I could easily track what was where. From that inventory, I was able to create a loose idea of what archival series I wanted and sort boxes on the shelf so the series were “living together.”

The biggest challenge was processing the correspondence. It was sorted into folders by year and month, but researchers often prefer access by correspondent name. Just taking the materials and sorting them A–Z would have required an amount of physical space for processing that just doesn’t exist; it would also destroy the ability to access the correspondence by year, as a whole. Physically, the materials are arranged chronologically, with correspondents filed alphabetically within each year. Each folder has an associated box and folder number. In the finding aid, correspondents are listed alphabetically as parent nodes. When you click on the parent node, you will see a child node for each year in which someone appears with a box and folder number. The correspondence series took the longest to process. Even taking the COVID lockdowns into consideration, it was around two and a half years of work. The rest of the collection was finished within another year.

Another issue was the microfiche. While we have a guide from when these materials were fiched, it’s not user-friendly if you’re unfamiliar. Kat Antonelli, digital archivist extraordinaire and my colleague, is putting together a finding aid for the fiche that will allow researchers to independently navigate the series.

Doel: Is there anything that is specific to archiving living scientists’ personal papers? What was the state of the collection when it arrived at APS (also, how did it arrive? were you part of that process?) and what is different now? Tongue-in-cheek question: can’t we just use collections as-is? They must come into an archive in perfect order, no?

Rinehart: One of the unique things about working on the collection of someone who is still living is that, sometimes, you’ll be able to meet them in person. It gives additional perspective to the person you’ll “meet” in the collection.

If collections could just be used as-is, it’d certainly make researchers’ lives interesting! One of the benefits of processing an archival collection is that all the material is described in a finding aid and rehoused for long-term preservation. While the Garwin papers came to the APS in very good condition, it isn’t unusual to encounter boxes of loose papers or files and having to figure out how they should be arranged or what they even mean!

Archivist Melanie Rinehart with the Garwin collection at the American Philosophical Society.

Courtesy of the American Philosophical Society

Doel: In what form did born-digital materials from the Garwin records come to you? What was in them?

Kathryn Antonelli, digital archivist: Believe it or not, Garwin sent us the born-digital materials via snail mail. The “physical carrier” he used (i.e. the storage device) was miniSD cards. The most common carriers we receive from donors are floppy disks for older collections and hard drives for more recent collections. Garwin’s born-digital collection is unique because he was very technologically adept and handled the migration of his old data himself from computer to computer over the years. His files include publications, papers, calendars, photographs, digitized photographic slides, and an incredible range of correspondence from transcribed telephone messages to typed copies of outgoing correspondence to proto-email to modern email.

Doel: What were the specifics of processing born-digital materials? How is the processing different from manuscripts?

Antonelli: Processing born digital materials is similar to processing physical manuscripts, but it comes with some additional considerations. In the pre-processing stage, the files must be ingested. This was simple with Garwin’s collection, but can be difficult if a collection arrives on deprecated physical carriers like floppy disks. Once the files have been scanned for viruses and safely stored on our server, duplicate files are removed. The files are also scanned for personally identifiable information. The most common things to find are social security numbers and phone numbers. Once it’s located, generally either the PII is redacted or the file is restricted. From there, the decision to arrange and/or rearrange the files, and the decision to rename any files or directories, is made on a case-by-case basis depending on the level of organization already set in place by the donor.

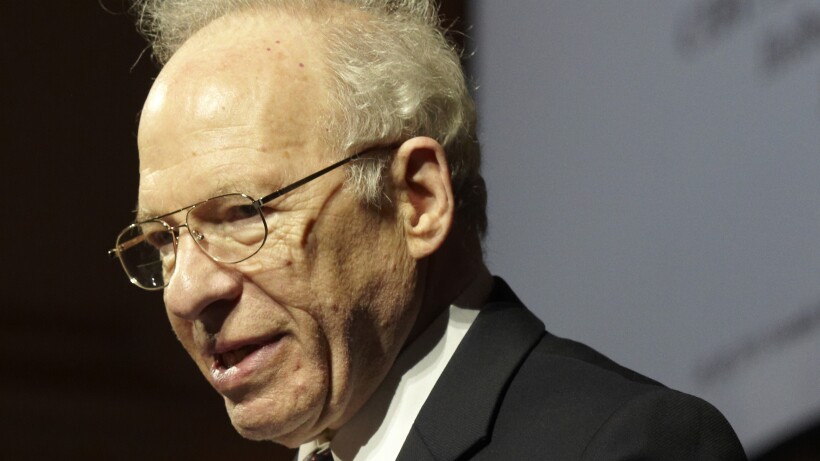

Richard Garwin in 2011.

Marianne Weiss / Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organization Preparatory Commission, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0

Doel: For paper records, access happens in the reading room, whether it’s working with hard-copy documents (originals or copies) out of a box or microfilm using a reader. What does access to born-digital material look like at APS? Can I just view them online?

Antonelli: There are three main ways to access born-digital material at APS, largely driven by the differing privacy restrictions and file formats of our collections. Most of our available born-digital materials can be accessed in the reading room. Researchers make an appointment and request materials, and access copies are temporarily loaded onto our Born-Digital Workstation for viewing. The second possibility for access is file transfers. On request, and after discussion with archivists, certain born-digital materials can be sent directly to researchers via file transfer. Eventually, materials appropriate for open public access will be added to our web-based Digital Library, where digitized copies of physical materials can also be found.

Doel: Digital processing is a fairly new field in archiving—how did you develop your expertise and where can others learn it?

Antonelli: Digital archivists come from many different paths. I hold a master’s in library and information science, and a digital archives specialist certificate from the Society of American Archivists. Much of my expertise comes from past work experience, but also from discussing challenges and successes with other digital archivists. The most interesting thing about digital archiving is that it must constantly evolve to keep up with new technologies. Once you understand the archival theory that grounds your goals, it’s very much a “learn on the job” type of field.

Anna Doel

American Institute of Physics

adoel@aip.org

You can sign up to receive the Weekly Edition and other AIP newsletters by email here