Telegram Congratulations to J.H. Van Vleck in 1935

Western Union Social Message heading

Exploring archives means getting to read other people’s mail. We can vicariously join in on moments of celebration from 90 years ago. Personal papers of scientists provide opportunities to explore aspects of scientific discoveries, but they also offer the ability to explore networks of connection and support in the scientific community.

AIP’s Niels Bohr Library and Archives

Van Vleck Papers on a cart in the Niels Bohr Library & Archives.

On a recent visit to NBLA, I explored a bit of the J. H. Van Vleck Papers

Physicist, astronomer, and acoustician Dayton Clarence Miller

Telegram from Dayton Clarence Miller

Roughly an hour later, at 1:32 PM, we have this message, ostensibly from mathematician George David Birkhoff

Message ostensibly from mathematician George David Birkhoff

The next day, at least two more telegrams were sent. The one below, time stamped 10:30 AM, presumably comes from chemist Linus Pauling

Telegram presumably from Linus Pauling and Edwin Kemble

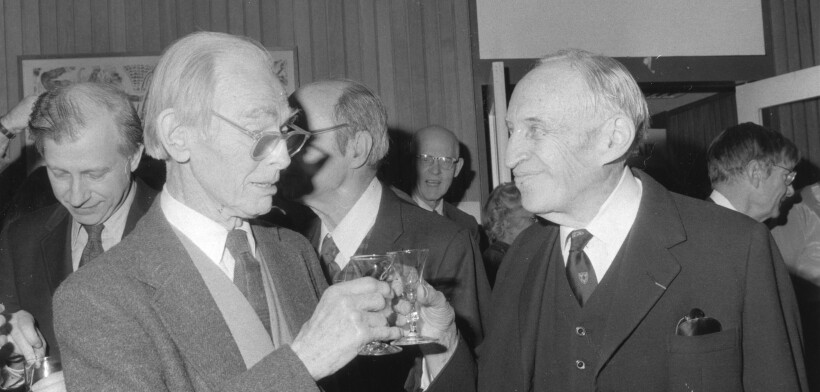

Thirteen years earlier, in 1922, Kemble had served as Van Vleck’s thesis advisor. Kemble and Van Vleck’s lifelong relationship is further documented in AIP’s collections. Twenty-seven years later, in 1962, Van Vleck and Thomas Kuhn would conduct this oral history interview with Kemble

Edwin Kemble (left) toasting with John Van Vleck (right) at Edwin Kemble’s 90th birthday celebration. Credit: E. B. Boatner, courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives. Kemble Edwin C3

Meanwhile, back in 1935, half an hour after the Kemble and Pauling telegram, at 11:02 AM, we have the telegram below. This one, signed “Compton,” is likely from physicist Karl Compton

Telegram likely from Karl Compton or Arthur Compton

In short, in this two-day period in 1935, five leading figures in the scientific community rapidly dispatched brief congratulatory telegrams to Van Vleck.

We gain insight into this practice of congratulatory telegrams from a letter in the same folder from physicist Raymond Birge.

Birge goes on to provide context, which is particularly useful to those of us leafing through this folder some 90 years in the future, on how this whole network of telegrams worked. He explains, “Since no one from the University of California was up for election, no telegrams were received here as to those elected, and since, as you may know (if you do not, this is quite confidential), the number of those nominated was in excess of the number that the Academy permits itself to elect at any one time, I could not be sure of your election until I got the official news. This did not come for several days, and I have also been extremely busy.”

What is it that we learn from reading through this folder of telegrams and letters in the J. H. Van Vleck Papers

Beyond that, the presence of these items in this collection tells us a bit about what mattered to Van Vleck. We have these messages because they meant enough to him to keep, presumably for decades, as part of his personal papers. Collectively, his papers mattered enough to him that he took the initiative to ensure a new life for them at AIP and planned for them to be donated to our collections. The archivists at the Niels Bohr Library and Archives saw the value of these materials and their relationship to our collections and invested time and energy in arranging and describing them so that people like us could come along in the future and explore them.

Like all documents in an archival collection, these messages are both records and documentation from a specific historical moment and a statement about what the record keeper (and subsequent stewards) thought was significant enough to care for and preserve. I hope more people in the scientific community today are inspired like Van Vleck to be deliberate in maintaining records of their work and collaborations to be preserved and explored like this in the future.