Mary Somerville’s book Mechanism of the Heavens beside Olivia Waite’s romance novel The Lady’s Guide to Celestial Mechanics. Credit: AIP

Find the corresponding podcast episode here: Initial Conditions - A Physics History Podcast

What do comet hunting, French translation, and sapphic romance all have in common? Two things actually: 1) they are the subject of this week’s episode of Initial Conditions: A Physics History Podcast

Mary Somerville’s book Mechanism of the Heavens beside Olivia Waite’s romance novel The Lady’s Guide to Celestial Mechanics. Credit: AIP

The main character in The Lady’s Guide, Lucy Muchelney, is based on a combination of Caroline Herschel (1750-1848), who was the first woman to officially discover a comet, and Mary Somerville (1780-1872), one of the most successful science writers of all time. The book is full of historical nuggets and makes science immersive and, dare I say, romantic. Waite tells the story of Lucy’s translation of a French celestial treatise, alluding to Mary Somerville’s translation of Pierre-Simon Laplace’s Traité de Mécanique Céleste.

The Lady’s Guide is also a story of identity. Too often women, people of color, and those who identify as LGBTQ+ have been erased from science history. Their scientific contributions or parts of their identity have been overlooked to fit the traditional narrative. Like many of Waite’s novels, this story is a celebration of Queer identity and love. In our interview, Waite shares that through writing this novel, she was able to explore her own sexual identity while rectifying the the lack of Queer representation. Interviewing Olivia Waite was a blast because she is not only an excellent writer, but a joy to speak with!

Author, columnist, and guest for this week’s episode, Olivia Waite

Photographer: Binh Nguyen

Because the interview with Olivia Waite speaks for itself, I would like to dedicate this blog post to talk about the lives and work of the two women behind The Lady’s Guide protagonist. Caroline Herschel was born March 16, 1750, into a poor family in Hanover, Prussia. She did not have an easy childhood: she contracted smallpox at age six that permanently scarred her and typhoid at ten that permanently stunted her growth. As an adult, she only grew to be 4’3” tall. Still, she had a fairly typical upbringing. Caroline received an elementary education complemented by additional courses in domestic skills like sewing and cooking. In her spare time, Caroline helped read and write letters for women in her village who were corresponding with their military husbands. Though her diaries reflect a genuinely selfless person, she occasionally did reveal her frustration that while her brothers could practice musical instruments like their musician father, she never had the time in between her domestic duties.

Portrait of Caroline Herschel. by Joseph Brown, after Unknown artist stipple engraving, circa 1842. Credit: National Portrait Gallery, London D9005

When Caroline was twenty-two, she was allowed (after some arguing) to join her brothers, William and Alexander, in London. Initially, William trained her in practical matters: English, mathematics for accounting, and taught her to sing to earn her own income. When William became fascinated by astronomy, he led Caroline and Alexander in a telescope-making astronomy team. He was concerned with the big picture and mathematics, while Alexander was a tinkerer and labored over details, making the eyepieces and complex metalwork. Caroline was the glue, seamlessly translating between brothers and assisting wherever she was needed.

Portrait of Caroline Herschel’s brother, William Herschel (1738-1822). Credit: AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, E. Scott Barr Collection. Catalog ID: Herschel William A10

In 1781, William Herschel discovered a strange new comet using his seven-foot telescope

Though William was rewarded for his discovery with the position of the King’s Astronomer, the Herschel siblings continued to sell telescopes to make ends meet. Caroline was often left with the grunt work: shifting horse-dung through a sieve to create molds

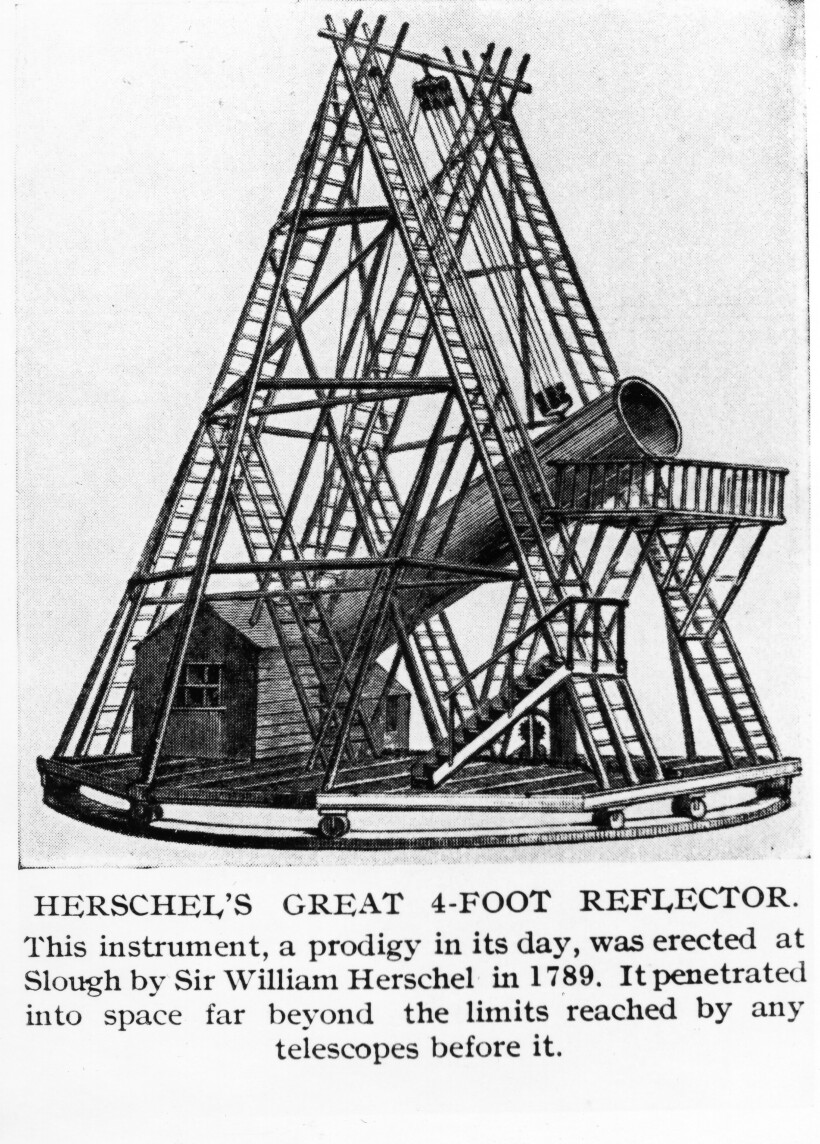

William made some of the biggest telescopes of the time, like this forty-foot long telescope, that required large structures to maneuver them. Caroline was in charge of overseeing the crew building and operating the telescope while William observed the night sky. Credit Line:AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Catalog ID: Herschel William F2

One night, in 1786, she was observing alone while her brothers were away delivering a telescope when she made a discovery. According to her notes:

1st August: I have calculated 100 nebulae today, and this evening I saw an object which I believe will prove to-morrrow to be a comet

2nd August: to-day I calculated 150 nebulae. I fear it will not be clear to-night, it has been raining throughout the whole day, but it seems now to clear up a little.

1 o’clock; the object of last night is a Comet. I did not go to rest till I had wrote to Dr Blagden and Mr Aubert to announce the comet”

Caroline and William worked around the clock: at night they would observe, then they would sleep a few hours in the morning. The rest of the day they performed calculations, conducted their regular business, and entertained guests. Caroline rarely had free time and visits by aristocrats often tried her patience. Not one for socializing, she made few close friends outside her family. The exceptions were the Royal Astronomer, Nevil Maskelyne, who was her constant supporter and confidant as well as Jérôme Lalande, a French astronomer and mathematician. It took many years for Caroline to accept such friendship and, because it was the 18th-19th century, she was hesitant to correspond directly with the men. It is not entirely surprising that she ultimately befriended them; both men were known for supporting women in the sciences.

In Caroline’s lifetime, she discovered eight comets. By her second comet, she earned a modest salary as William’s astronomical assistant and became a paid astronomer. Still, she was careful about how she announced each discovery. Sometimes her announcements were merely tucked into her brother’s catalogs. She knew she had to walk a fine line of confidence and humility in order to be respected, but not threatening.

Comet hunter and cataloger of nebulae, double stars, and star clusters would have been impressive enough on its own, but potentially Caroline’s most important contribution to science was her organization of celestial objects. Previously, star charts such as Flamsteed’s Star Catalog (1725), the standard in England, were designed for navigation and were ordered by constellations. For astronomy, this was impractical and meant that many stars were counted twice while others were missed. She took on the tedious work of creating a new, organized index, cross-referencing the known catalogs and conducting her own observations to supplement. She was able to do this when William’s scientific interests diverted him from topics that required her assistance. It is worth noting that she embarked on this project while her older brother, Jacob was visiting. It is possible that she wanted to stay busy to avoid Jacob, who was a very controlling, arrogant man who believed women should stick to domestic duties. Either way, the publication of this index was an incredible scientific achievement. Even humble Caroline, ever cautious to share any emotions, expressed to her friend, the Royal Astronomer, Nevil Maskelyne:

But your having thought it worthy of the press has flattered my vanity not a little. You see, sir, I do own myself to be vain, because I would not wish to be singular; and was there ever a woman without vanity? or a man either? only with this difference, that among gentlemen the commodity is generally styled ambition.”

Caroline Herschel lived to 97 and was showered with accolades. She always took care of her family and helped raise her nephew, William’s son, John Herschel and nurtured in him a love of astronomy and a respect for women in science.

Portrait of Mary Somerville by Thomas Phillips (1834)

Mary Somerville was born as Mary Fairfax, thirty years after Caroline Herschel, on December 16, 1780. Her experience as a woman in science differed greatly from that of Caroline Herschel. Unlike Herschel, who was often modest about her accomplishments, Somerville boldly embraced her status as a scientist. Mary Somerville was the first scientist–in fact, William Whewell coined the word “scientist” in 1834 to describe her. She rose to fame for her translation of Pierre-Simon Laplace’s Traité de Mécanique Céleste, a highly technical French work that described a mechanical universe. She continued scientific writing and published over a dozen other scientific works, many of which were used as college textbooks. Her autobiography, Personal Recollections

Few thoughtful minds will read without emotion my mother’s own account of the wonderful energy and indomitable perseverance by which, in her ardent thirst for knowledge, she overcame obstacles apparently insurmountable, at a time when women were well-nigh totally debarred from education.

I was annoyed that my turn for reading was so much disapproved of, and thought it unjust that women should have been given a desire for knowledge if it were wrong to acquire it.” -Mary Somerville

Though her family worried about Mary’s marriage prospects given her academic eccentricities, they did not need to. Her daughter wrote that she was beautiful, sociable, and a favorite dance partner of many. Mary eventually married twice. She married her first husband, Samuel Grieg, in 1804 after her father passed away. It was an unhappy marriage however, and he disapproved of her academic pursuits. Samuel Grieg died just a few years after they married, leaving Mary a widow (this was, I hate to say it, fortunate for her). No longer bound by her loveless marriage, she had the financial freedom to spend her time doing what she loved: learning.

Mary’s second husband, William Somerville, was the oldest son of Mary’s supportive uncle. William was a member of the Army medical board and had lived almost exclusively abroad until he returned home and fell in love with Mary. He was intelligent and had a passion for learning but was more supportive of Mary’s academic pursuits than his own. Their daughter wrote,

He was far happier in helping my mother in various ways, searching the libraries for the books she required, indefatigable copying and recopying her manuscripts to save her time. No trouble seemed too great which he bestowed upon her; it was a labour of love.”

William’s father was happy with the marriage; he mentored Mary and loved her, but the extended family did not share his affection. Like Mary, William was considered liberal, and he was distant from much of his family because of it. Mary herself was bold about her politics. From a young age she was anti-slavery, and as an adult she advocated for animal rights and women’s rights. The unconventional gender roles Mary and William played in their marriage made William’s family uncomfortable.

The couple moved to London in 1816 and traveled to visit other scientists. They took a trip to Switzerland where they met the famed mathematician, the Marquis de Laplace. Her French was best when discussing scientific subjects because that’s where she encountered the language most, and she talked to Laplace at length about astronomy and calculus. This meeting has been described by multiple different versions of the same fable: Laplace was rumored to have said that Mary Somerville was one of three women in the world who could understand his text. The other two were Mary Greig and Mary Fairfax–her other names. But, it doesn’t really matter how the fable goes, either way, it was clear that Mary impressed the Marquis. For more about Laplace, check out the post Pierre-Simon Laplace Speaks

Portrait of Marquis Pierre-Simon Laplace. Credit: AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Physics Today Collection. Catalog ID: Laplace Pierre A1

Mary Somerville easily befriended many of the scientists she admired. She established a deep friendship with John Herschel, Caroline’s nephew, who had grown into an astronomer and mathematician, and became close to Charles Babbage who was working on a theoretical calculating machine. She mentored Ada Lovelace who wrote a theoretical program for Babbage’s calculating machine, making Ada the world’s first computer programmer.

In 1827, Lord Henry Brougham, representing the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, recruited Mary to translate Laplace’s Traité de Mécaniques Céleste. After much convincing, Mary agreed, with the promise that it would remain a secret and would be burned if it were unsuccessful. This wasn’t the first time she had attempted to burn one of her scientific endeavors. The previous year, she had conducted an experiment on the magnetism of the sun’s rays that was accepted by the Royal Society–the first experimental paper by a woman. It was later disproved and she was so horrified by the occasion that she burned all evidence and never mentioned it in her Personal Recollections. But it wasn’t easy for Mary to secretly undertake this complex translation because of her household duties. She arose early in the morning to get all her household tasks done, including taking care of her family and teaching her children for a few hours a day, leaving very little time to write in the afternoon. Even then she was constantly interrupted by friends and acquaintances who took up hours of her working time.

Mary expanded on Laplace’s work, adding narrative, explanations, and more details to make it accessible to a broader audience. When she finished the manuscript four years later, Lord Brougham deemed it too long. John Herschel, however, insisted it be published. Mechanism of the Heavens, as she titled it, was printed in 1831 and escaped what would have been a fiery fate. It received great praise, hundreds of copies were easily sold, and she was elected an honorary member of the Royal Astronomical Society, along with Caroline Herschel. Referring to Caroline, Mary wrote

To be associated with so distinguished an astronomer was in itself an honour.”

I wrote because it was impossible for me to be idle.”

Mary, ever restless, was working on yet another project that tapped into her geological interests. She finished Physical Geography which covered new developments in understanding the formation of the world. As new fields of scientific study emerged, Mary covered them, and in 1869 she wrote Molecular and Microscopic Science. By the time of her death in 1872, at age 92, she had written Mechanism of the Heavens, nine editions of The Connections of the Physical Sciences, seven editions of Physical Geography, On Molecular and Microscopic Science, and Personal Recollections. She was an honorary member of the Royal Astronomical Society and was awarded the Patron’s Medal of the Royal Geographical Society among other honors.

Like Caroline Herschel, Mary Somerville learned to walk the line of femininity. As a woman, she had to be resourceful to learn and had to rely on the men in her life to make connections and provide access to scientific society. And this brings us back to our theme of identity. Neither woman could freely pursue science without careful consideration of how their identity was accepted by the scientific community. Many scientists have had to hide part of their identity in order to be accepted, some did not make the choice willingly. Authors like Olivia Waite are helping rectify the lack of representation of LGBTQ+ scientists. Through historical romance, we can move forward and build a scientific community where people’s identities are not hidden or compensated for by careful letters to scientific allies, but instead welcomed and celebrated. If you are looking for resources that highlight LGBTQ+ figures in physics, Ex Libris Universum has compiled a list of podcasts

You can listen to Initial Conditions: A Physics History Podcast wherever you get your podcasts. A new episode will be released every Thursday so be sure to subscribe! On our website

Olivia Waite Website: https://www.oliviawaite.com/

A lady’s Guide to Celestial Mechanics: https://www.worldcat.org/title/ladys-guide-to-celestial-mechanics/oclc/1109806303

Alic, Margaret. Hypatia’s Heritage: A History of Women in Science from Antiquity through the Nineteenth Century. Boston: Beacon Press, 2000.

Kent, Deborah. “The Curious Aftermath of Neptune’s Discovery.” Physics Today 64, no. 12 (December 2011): 46–51. https://doi.org/10.1063/pt.3.1363

Somerville, Mary, and Martha Somerville. Personal Recollections, from Early Life to Old Age, of Mary Somerville with Selections from Her Correspondence by Her Daughter, Martha Somerville. Google Books. Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1874.

Winterburn, Emily. The Quiet Revolution of Caroline Herschel: The Lost Heroine of Astronomy. Stroud: The History Press, 2017.

Subscribe to Ex Libris Universum

Catch up with the latest from AIP History and the Niels Bohr Library & Archives.

One email per month