In early 2019, the Niels Bohr Library & Archives (NBLA) acquired a book of particular interest to both the history of science generally and our personal history as an archive: Emilio Segrè’s own copy of the physics textbook he wrote, Nuclei and Particles: An Introduction to Nuclear and Subnuclear Physics (1965).

Buckle up: this is about to get pretty nerdy.

Physics textbooks have something of a reputation for being on the dry side, especially older ones written for a university-level audience, as is the case with Nuclei and Particles. However, I would argue that there are elements of these older physics textbooks that spark interest and lines of intrigue, even in a non-physicist such as myself.

Firstly, we can consider why this book is important to the NBLA collections. At a basic level, this book fulfills two basic collection development strengths: physics texts since 1850 and successive editions of texts. We like to collect successive editions of books because there is great scholarly value in a comparison of editions, and we already had two other printings/editions of this work1. In terms of the book itself, as a researching physicist and later a professor, Segrè contributed actively to many journals, but Nuclei and Particles his only book-length work on physics, and as such, it offers a uniquely overarching view of what he thought was important in the field (at least for university students).

Rosa Segrè. Credit: AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Photo ID Segre Emilio G32

His autobiography devotes a paragraph to his work on Nuclei and Particles in which he gives his main reason for writing the book: he was teaching a class on nuclear physics at the University of California, Berkeley, and he thought none of the available nuclear physics teaching materials were up to date or appropriate for students at the time of his writing2. Though this was his only physics textbook, Segrè became a historian of science later in life and wrote a number of books on the history of physics, including a biography of his former advisor, Enrico Fermi. NBLA is lucky to have Segrè’s photograph collection - he was an avid photographer throughout his life - and our photo archive is called the Emilio Segrè Visual Archives in his honor. NBLA’s deep connection with Emilio Segrè is due in large part to the actions of his second wife, Rosa Segrè, who endowed the photo archive and donated Emilio's photos and several of his books to NBLA in her will. Thank you Rosa, we are in your debt!

In terms of the new-to-us book in question, perhaps the most exciting aspect for historians and book scholars is that we know the provenance of our copy of the book and its accompanying marginalia; it definitively belonged to Emilio Segrè, and it is chock full of his markings. This is quite rare. A fair number of our books have marginalia, and we can sometimes make an informed guess on its origins, but more often than not we can’t say for sure where it came from.

What does our new book look like? Let’s dive in!

Left to right: First edition first printing (1964), the new book - first edition second printing (1965), and second edition first printing (1977)

Nuclei and Particles was first published in 1964. The first edition was printed three times, each with corrections. The second edition appeared in 1977 and had several reprints with corrections. NBLA already had the first edition, first printing, and the second edition, first printing. The book in question that formerly belonged to Emilio Segrè is the first edition, second printing, and includes a 16-page printed pamphlet of errata for the first printing - that is, corrections for the first printing. I was happy to examine all three textbooks and consider the differences between them.

The corrections start as soon in the text as the title page. Emilio Segrè was an Italian immigrant, and as such, his last name includes an accent not typically used in English: “è.” One might wonder how he felt about his name inevitably getting misspelled in his adopted country, the U.S. Well, we have a small clue from this book: he certainly cared about the accent3! Interestingly, this mistake appears to be a new one, as the 1964 first printing’s title page has the accent. In a fit of bibliography nerdiness, I will also note that our catalog record for this printing reflects the missing accent - Segre - while the other printing and edition have the accent on both the book and in the catalog record.

Title page shows Emilio Segrè's corrections: an accent "è" on his last name.

He even added the accent to his book owner's stamp!

Book owner's stamp with corrected "è."

Emilio Segrè in Turin, Italy, during January 1963. He would have been planning or possibly working on Nuclei and Particles at this time. Credit: AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Segre Collection, Catalog ID Segre Emilio A24

The preface does not have any markings, but it reveals Segrè’s thought process for writing the textbook. “This book is addressed to physics students, chemists, and engineers who want to acquire enough knowledge of nuclear and subnuclear physics to be able to work in this field.” He goes on to say that it is meant to be an introduction, written as simply as possible, though compatible with a professional understanding of the subject. A comparison with the preface of the second edition (1977) reveals that he may have succeeded in keeping this introductory textbook at a professional level (which I imagine is not an easy task): “It gave me great pleasure to find out that colleagues often consulted the first edition for orientation in areas remote from their specialty, and to discover that in several physics libraries the book looks soiled and worn from the use it has had.”

He discusses the structure of the book and states that he believes that an introduction to nuclear physics should be the same for both the future experimental physicist and the future theoretical physicist, though he later also acknowledges that his own experience is theoretical and that this might have some impact on the general outlook and tone of the text. He recognizes that his book does follow some of his own areas of expertise and knowledge, making the parts of nuclear physics better known to him more prominent in the text. At the end of the preface, he also makes sure to acknowledge that any errors in the text are his own. This gives me the impression that he cared about the integrity of his work and that he had a realistic sense of his own limitations.

Elfriede Segrè. Credit: Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Catalog ID Segre Emilio G42

We get a few more clues about his personal life from the preface. Much of the material in the book comes from his own lectures and from Enrico Fermi’s notes (collected by Orear, Rosenfield, and Shluter) - which is not terribly surprising as Segrè was Fermi’s student - and we see some of Fermi’s influence on Segrè, even several decades after their professor-student relationship in the 1920s. Segrè also thanks eleven colleagues for giving feedback on the book, Mrs. Patricia Brown for patiently typing the manuscript, and his first wife Elfriede Segrè for compiling the index. Again, we see Segrè’s wife playing a vital role in his career, much like Rosa did with the Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, and clearly, creative and intellectual collaboration was vital to Segrè in the making of this book. We can imagine that this applied to other aspects of his professional and personal life.

Going further into the book, the majority of the markings are corrections and additions in preparation of the third printing of the first edition, which came out later the same year (1965), or possibly for the second edition (1977). This is where I would sorely hope that a physicist or historian of physics will one day take a deep look at this book, as my own knowledge will only allow me to make very basic observations.

Here, he added to an equation:

Page 23 addition to equation.

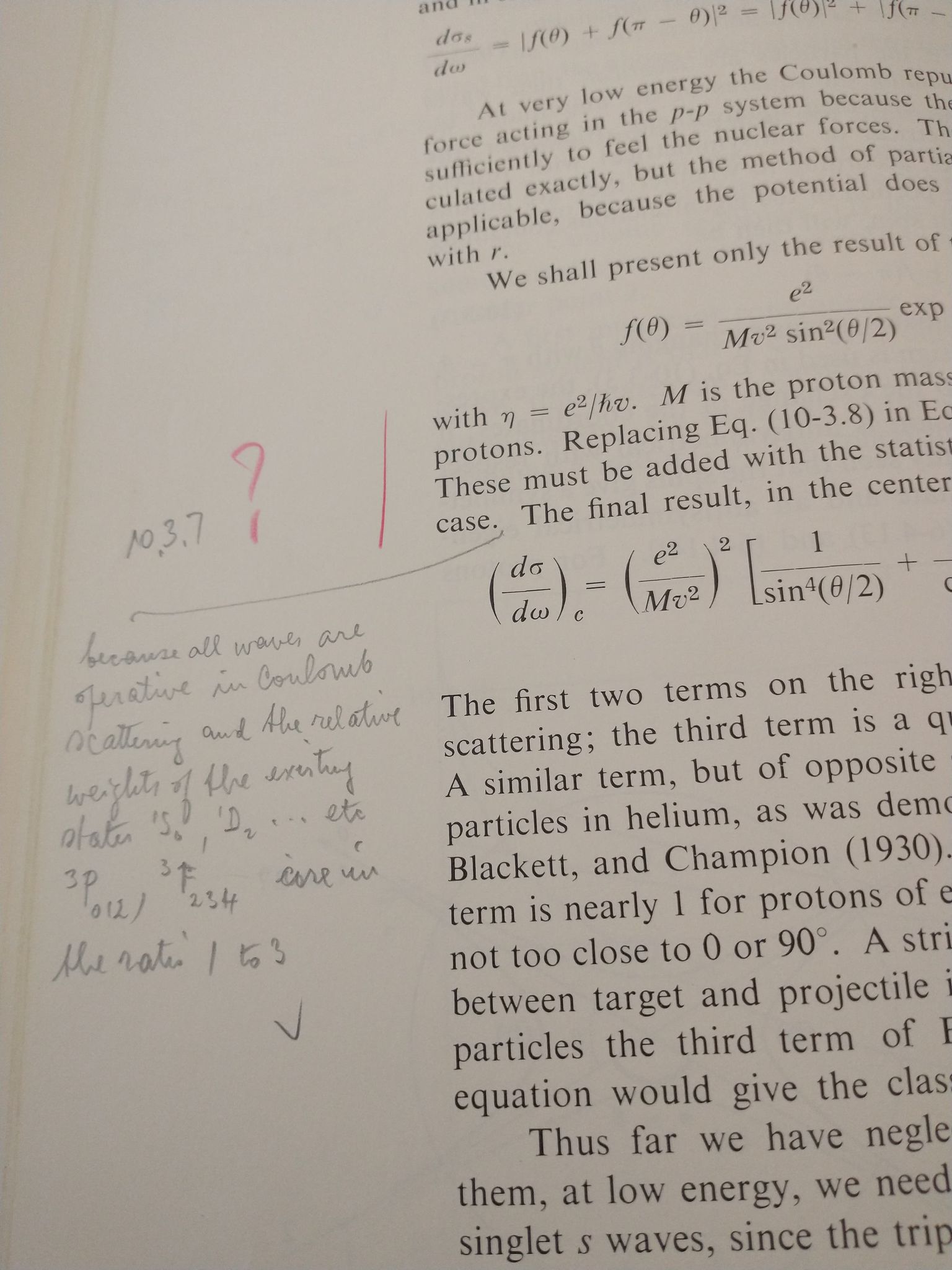

On a different page: He must have felt that this part needed further explanation. It reads something like (as best as I can make out): “because all waves are operative in Coulomb scattering and the relative weights of the existing states 1So, 1D2 … etc. 3P012, 3F234 core in the ratio 1 to 3.”

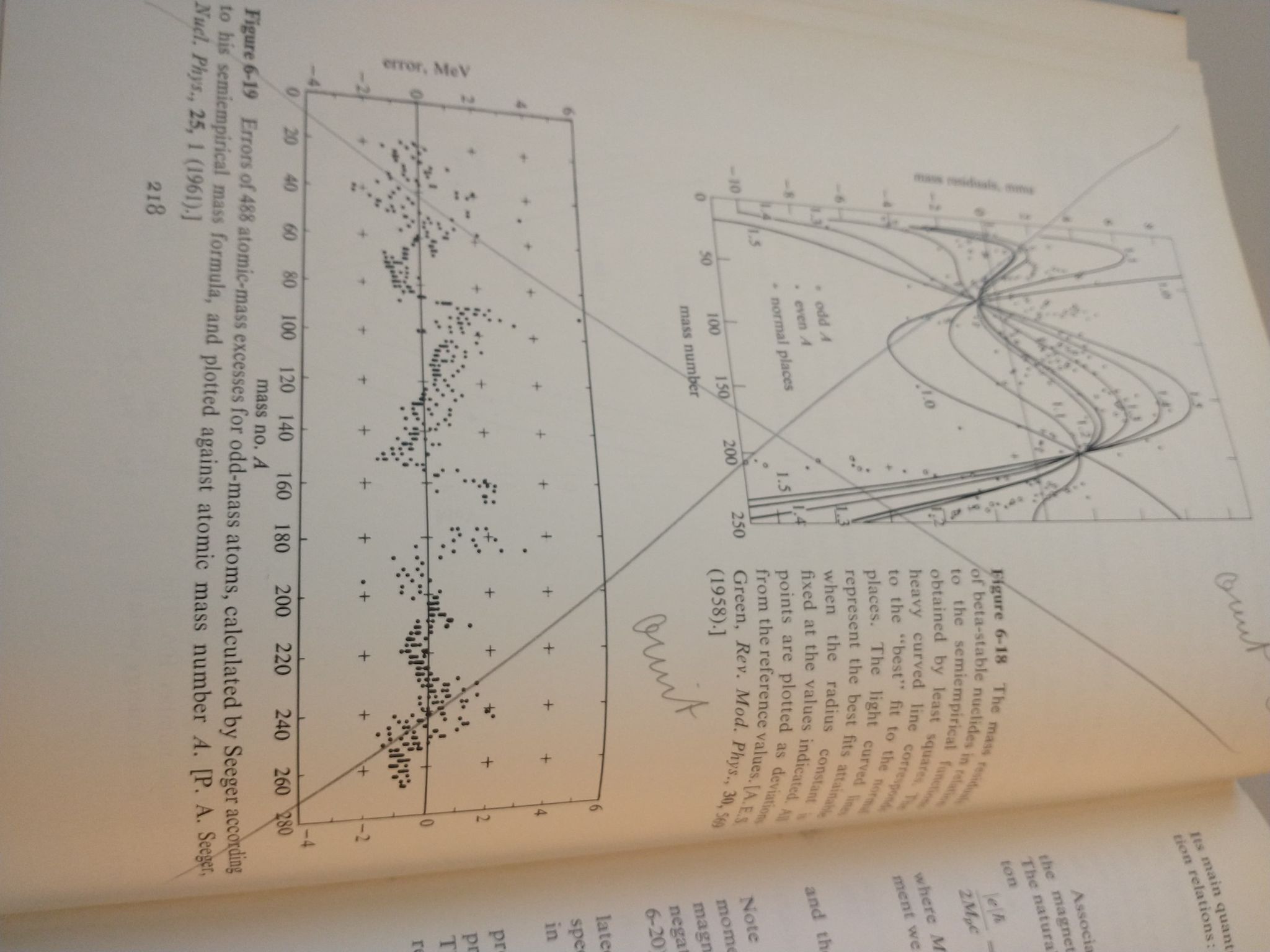

In this case, he decided to completely take out two figures (written word is “omit”):

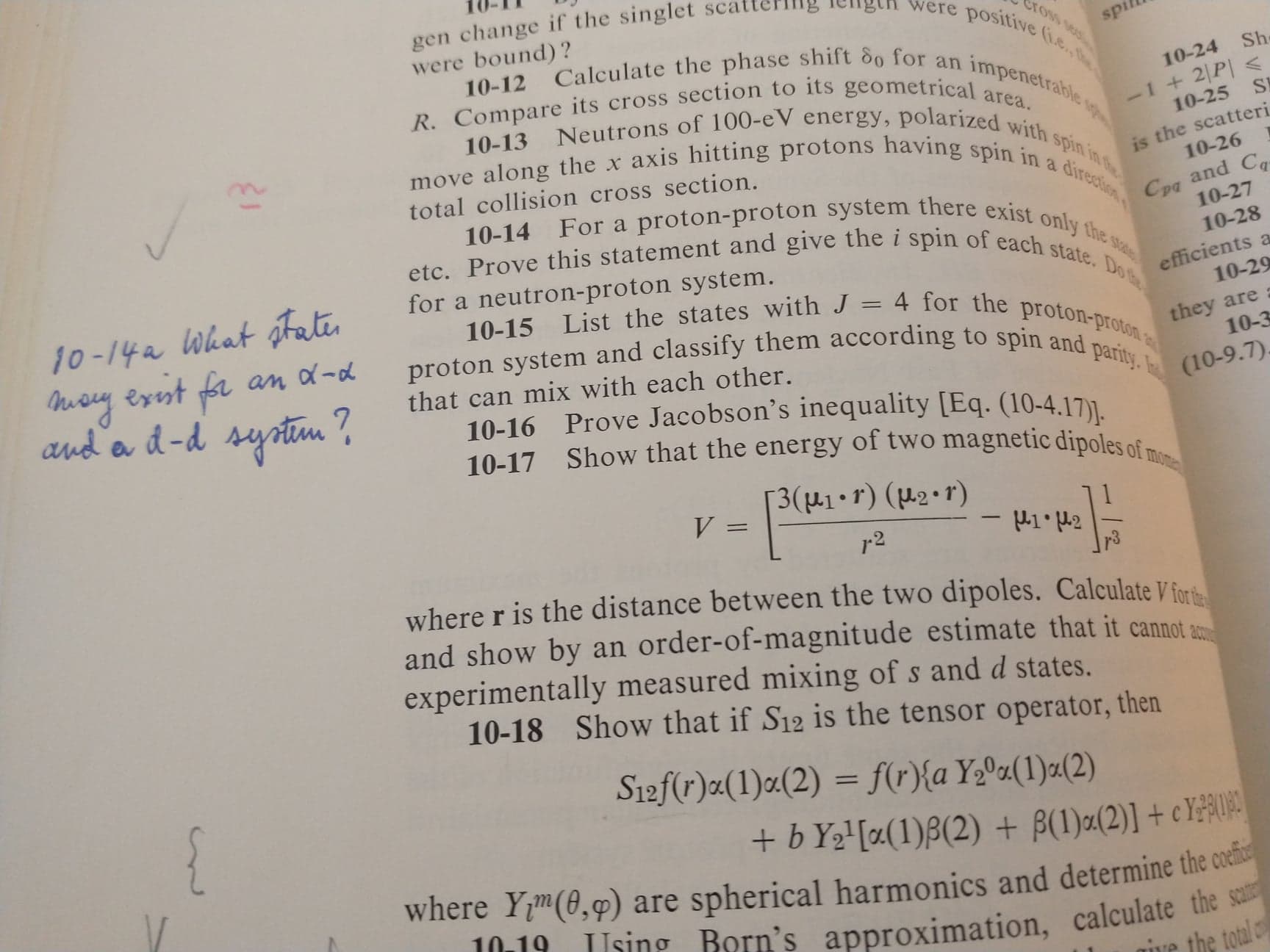

On this page, he wanted to add a question for students to answer as 10-14a: “What states may exist for an α-α and a d-d [deuteron-deuteron] system?”

In the second edition, we see that this becomes question 10-16.

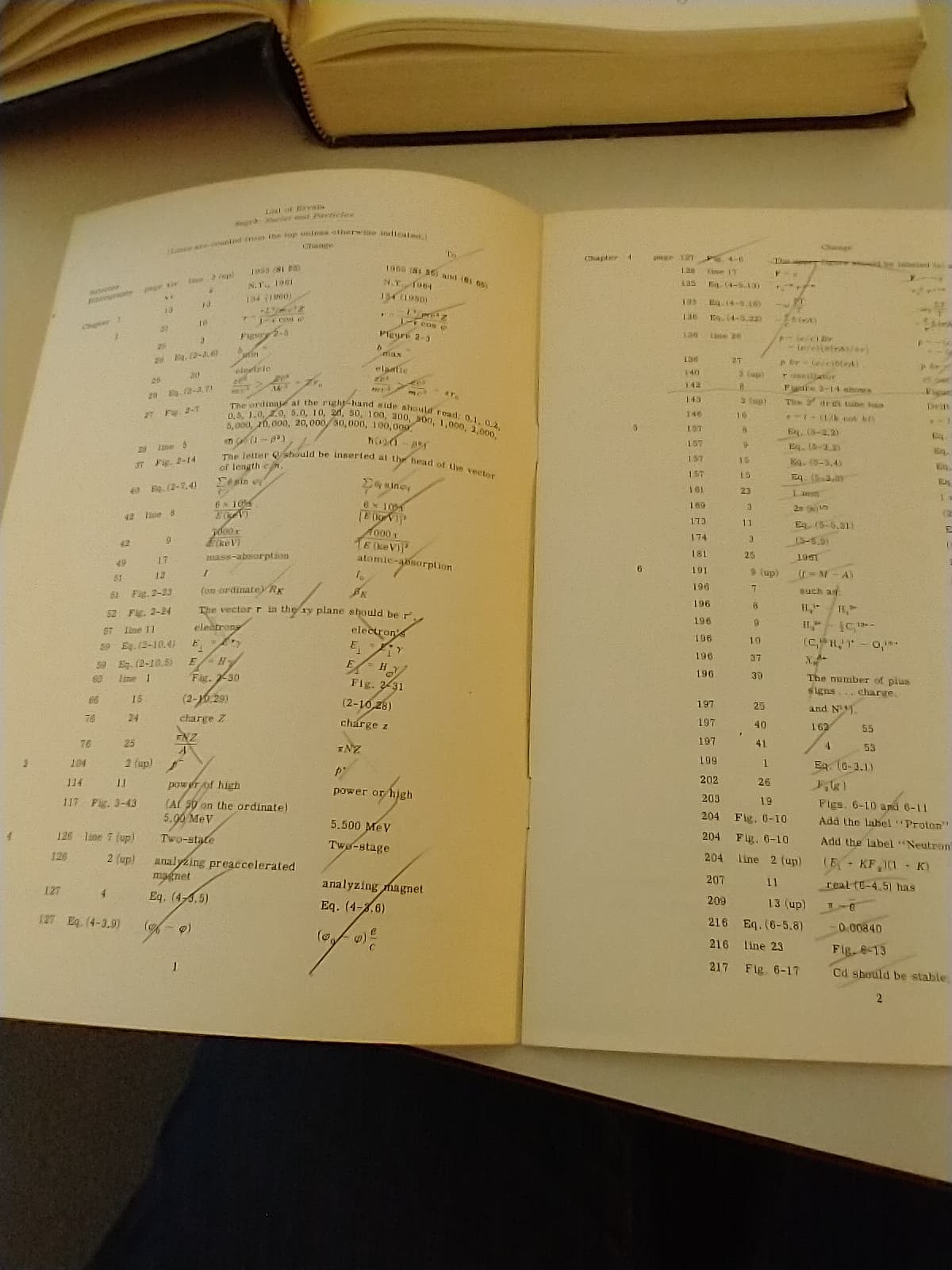

Tucked inside of the book was this List of Errata for the First printing. Note that he corrected the “è” here as well!

List of Errata for the First Printing title page with Emilio Segre corrected to Emilio Segrè

It appears that he went through every mistake from the first printing and made sure that they were corrected in the second printing. There were nearly 700 corrections to the first printing. The amount of work that went into writing the book and correcting it many times must have been quite a bit. In his autobiography, Segrè notes that the book took five years to complete2. I imagine that it must be frustrating for physics students struggling to learn concepts for the first time to encounter mistakes, but that they must be common in texts of this size.

Lists of corrections, checked off by Emilio Segrè

When we’re open to the public again, I hope you’ll consider coming in to take a look at this piece of physics education history.

*Special thanks to Christian Westergaard of Sophia Rare Books for excellent record keeping and for giving information on the book two years after the sale. Much gratitude also to my colleague Audrey Lengel for providing background research on the origins of the Emilio Segrè Visual Archives.

1) For more great articles on this topic, see Conceptual Physics and A Tale of Two Editions.

2) Found on page 280 of A Mind Always in Motion: the autobiography of Emilio Segrè, published by the University of California Press in 1933.

3) (Similarly, I was very disappointed by this New York Times article for dropping the “å” in the name of the winning Eurovision band Måneskin, but I digress.)

Add new comment