Ex Libris Universum: From the Library of the Universe

Ex Libris Universum: From the Library of the Universe

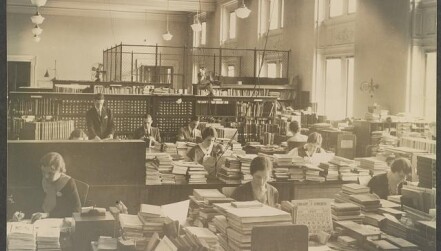

This blog, published by AIP’s Niels Bohr Library & Archives, intends to do just that - bring you into the library of the universe. The librarians, archivists, historians, and special guest authors featured on this blog provide a behind the scenes look at the history and collections they preserve and make accessible, the hidden figures and stories they make known, and the services they provide to the history of science community and the public. To subscribe, scroll to the bottom of the page, select “AIP History Monthly Update,” and enter your email address.

Do you have feedback, or a lead on a great post for the blog? Reach out to us at: nbl@aip.org

Latest Articles

Photos of the Month

More Photos of the Month

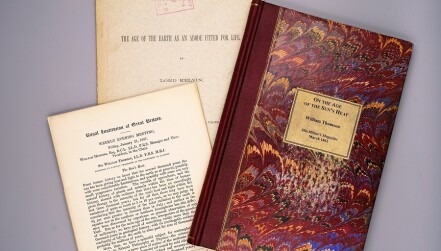

Collections Spotlight

Interviews

Behind the Scenes

Wikipedia Dispatches

Librarian Recommendations

All Articles

Subscribe for Updates

A quantum of history in your inbox every Friday.

One email per week

Catch up with the latest from AIP History and the Niels Bohr Library & Archives.

One email per month

Receive updates on education and employment trends for physical scientists.

One email per month

Send the above selected newsletters straight to my inbox!

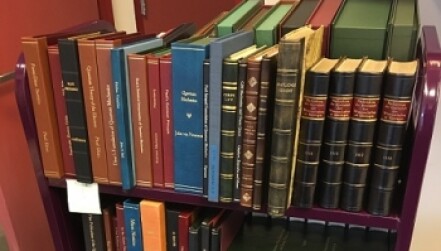

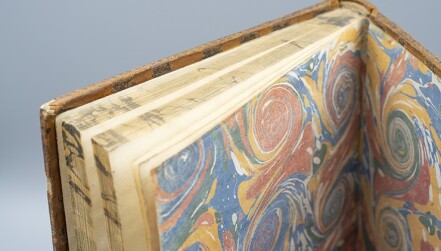

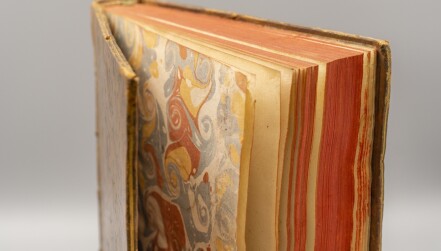

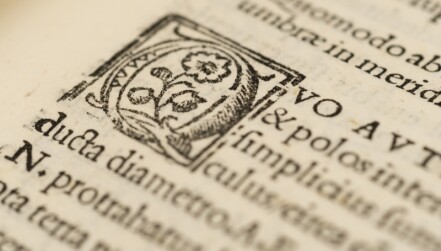

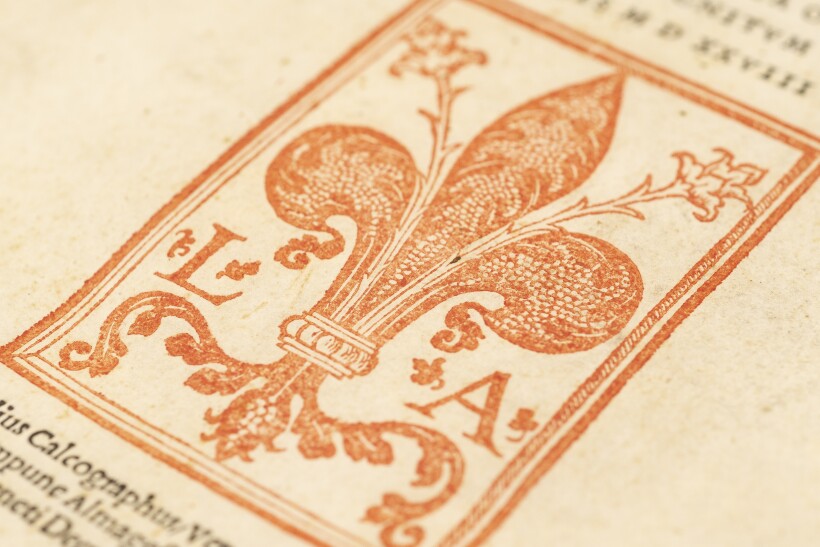

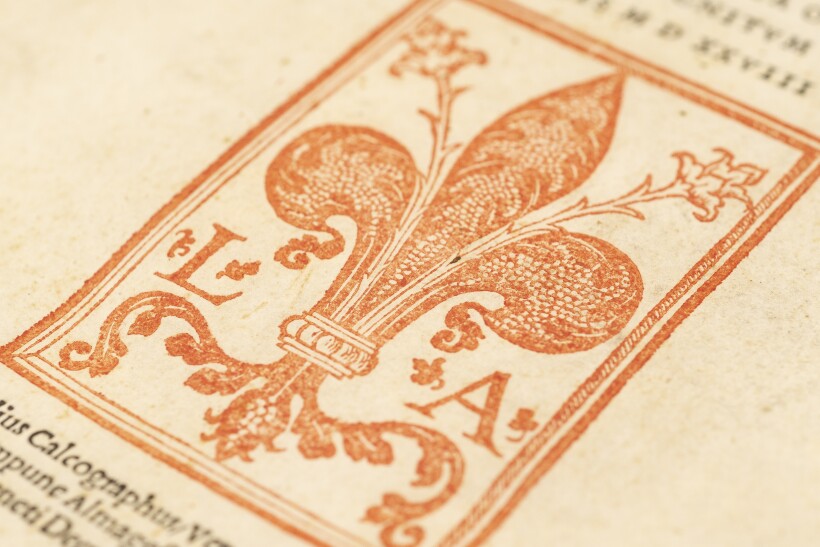

Ptolemy’s Almagest,1528. Image by AIP.