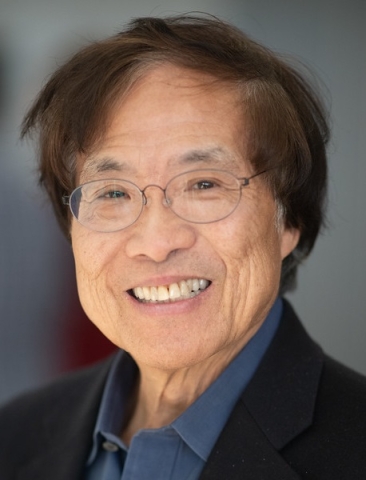

John Fan

Notice: We are in the process of migrating Oral History Interview metadata to this new version of our website.

During this migration, the following fields associated with interviews may be incomplete: Institutions, Additional Persons, and Subjects. Our Browse Subjects feature is also affected by this migration.

We encourage researchers to utilize the full-text search on this page to navigate our oral histories or to use our catalog to locate oral history interviews by keyword.

Please contact [email protected] with any feedback.

Credit: Kopin

Usage Information and Disclaimer

This transcript may not be quoted, reproduced or redistributed in whole or in part by any means except with the written permission of the American Institute of Physics.

This transcript is based on a tape-recorded interview deposited at the Center for History of Physics of the American Institute of Physics. The AIP's interviews have generally been transcribed from tape, edited by the interviewer for clarity, and then further edited by the interviewee. If this interview is important to you, you should consult earlier versions of the transcript or listen to the original tape. For many interviews, the AIP retains substantial files with further information about the interviewee and the interview itself. Please contact us for information about accessing these materials.

Please bear in mind that: 1) This material is a transcript of the spoken word rather than a literary product; 2) An interview must be read with the awareness that different people's memories about an event will often differ, and that memories can change with time for many reasons including subsequent experiences, interactions with others, and one's feelings about an event. Disclaimer: This transcript was scanned from a typescript, introducing occasional spelling errors. The original typescript is available.

Preferred citation

In footnotes or endnotes please cite AIP interviews like this:

Interview of John Fan by David Zierler on January 1, 2021,Niels Bohr Library & Archives, American Institute of Physics,College Park, MD USA,www.aip.org/history-programs/niels-bohr-library/oral-histories/XXXX

For multiple citations, "AIP" is the preferred abbreviation for the location.

Abstract

In this interview, David Zierler, Oral Historian for the American Institute of Physics, interviews John Fan, CEO and Founder of Kopin Corporation. Fan explains the origins of the name Kopin and discusses how the company has fared during the pandemic. He recounts his childhood first in Shanghai and then in Hong Kong and he discusses the opportunities leading to his undergraduate admission at UC Berkeley, where he studied electrical engineering. He describes a formative internship at the IBM Thomas Watson Lab. Fan explains his interest in pursuing a PhD at Harvard in Applied Physics and Engineering and he discusses the exciting technological developments coming online from Boston-area companies in the early 1970s. He describes his thesis research on vanadium oxide conducted under the direction of Bill Paul. Fan discusses his collaborations at MIT’s Lincoln Lab and the process of creating Kopin. He reflects on his long tenure as CEO of Kopin and emphasizes the central importance of business integrity as the key to longevity. Fan conveys his interest in wearable technologies and Kopin’s work at the cutting edge of this field, and he muses on the extent to which wearables are a harbinger for a fuller interface between biology and technology. He discusses the impact of supercomputing on Kopin’s operations, and he survey’s his contributions to LCD and LED technologies. Fan prognosticates on the long term impact of artificial intelligence and the utility of virtual reality, and at the end of the interview, he emphasizes that technology should always be applied to the fundamental effort to improving the lot of humanity.

Zierler:

This is David Zierler, oral historian for the American Institute of Physics. It is the 1st of the new year, 2021, and I’m so glad to be here with Dr. John C.C. Fan. John, it’s great to see you. Thank you so much for joining me today.

Fan:

Thank you, David. Thank you for inviting me.

Zierler:

To start, would you please tell me your title and institutional affiliation?

Fan:

I’m John Fan. I’m the CEO and founder of Kopin Corporation, which is headquartered in the Boston area.

Zierler:

What does the name “Kopin” mean?

Fan:

That is a very interesting story. When we started the company, which is 1984, so many years ago, I was at MIT Lincoln Laboratory, and then we were actually working on a very interesting technology called nanotechnology. [laughs] At that time, we didn’t even call it “nano.” We called it “wafer engineering.” That means, we actually designed new materials. We tried to splice materials together, combine materials which atomically have different structures and try to combine them without any rejection. And at that time, this novel technology was going well, and we were becoming quite famous, and of course it was typical at that time, venture capitalists were attracted by this technology and came to discuss spinning this novel technology out.

Also, at that time, I was very fortunate to have two very good friends; one in financial area, and the other in patents IP area, encouraging me to start our new company. Remember Genetech just got spun out a few years ago before ours and was started by a famous venture group VC called Venrock, which is part of the Rockefeller Group. They started Genetech. They also started Apple. After they talked to me, I went to see the director of Lincoln Lab, and he said MIT encouraged new technology to be commercialized. MIT, as you know, is always very forward-looking. They would love to take technology into the commercial world. So, we went ahead starting a company with VCs. Then we had to decide: what should be our company’s name? What kind of name should we do? And at that time, you may also know that in those days, folks liked names such as Xerox, Kodak — the names have no meanings, but it’s two syllables, it sounds good, and people will remember. It’s easy to pronounce. So, I asked my father. As is typical in the Asian way, you ask your father: what should be the name! So, it was him that picked the name. He picked the name “Kopin.” Well, it so happened, Kopin is also close to the name of his own company, a chemical manufacturing company. “Ko” actually means “very high quality, high performance.” “Pin” means “very equitable, very flat, a fair price.” So, the name “Kopin” is actually two Chinese characters. It means very high-quality product with very equitable or fair price.

Zierler:

Oh. That’s a perfect name. [laughs]

Fan:

[laughs] Yeah. It means nothing in English. But there was an interesting story behind it. About six or seven years later, I was in Helsinki. I was visiting, at that time, Nokia. We were actually thinking about — you wouldn’t believe it. We – Kopin and Nokia, were actually, at that time, really thinking about how to put a phone on one’s head so one could have hand-free phone. And when I walked out of the airport, and there was this huge bus. And there’s a sign that said “KOPIN.” And I looked at it. I mean, I was stunned. I said, “Wow! Nokia brought along a whole big, tall bus with a big KOPIN sign, welcoming me.” It so happened that it wasn’t. “KOPIN”, at that time, was the name of a big bank in Helsinki. [laughs] So, it is not so rare. There are folks whose last name is “KOPIN.”

Zierler:

John, we’re going to take the narrative all the way back to the beginning, but I’d like to ask first a very present question, and that is: there is, of course, a clear physicality to your company. Right? There’s a need to work with materials, to be in the lab, and to have that interaction. And so, I’d like to ask: how has your company coped in the pandemic? How have you been able to — and successfully, over the past year — continue with your product research, given the nature of the pandemic and the requirements of social distancing?

Fan:

That’s a wonderful question, David. Kopin actually thrived very well through this pandemic, and at the end of the year, obviously, being CEO and chairman, I reflected upon it — why we have been so successful. I think there were several different elements to it. First is: our company, as you well know — we have gone through several cycles of ups and downs. We are now entering our up cycle. And in the last cycle, we were actually focused on phones. We developed and manufactured a HBT – heterojunction bipolar transistor product — a power transistor, to use in a phone, enabling an analog phone transformed to a digital phone then later to a computer smart phone. In fact, today HBT is used in every smartphone. But about five years ago, we decided to sell the business of making HBT transistors for the phones and to focus on wearables. I believe that the next wave is to transform a handheld computer, which is in a smartphone, to be worn on our body, hands-free.

So, personal computer and communicator will be hands-free, in particular — in my view, it should be incorporated into the eyeglasses that you and I wear. Okay? This has been our dream for several decades, and five years ago, we’ve decided that the transformation was near and we made the radical change, moving the whole company from handheld smart phones focus to hands-free wearable devices. I was wrong, of course. Wrong in several ways. Wrong — it was too early. I mean, like typical guys from MIT. [laughs] They see things too much into the future. And then they’re so cocky, they think that they can make the future come now. Okay? Unfortunately, we’re still human. We couldn’t do it at the pace we wished for. We actually were way too early. However, this pandemic changed everything. Pandemic makes everybody stay at home. Everybody has been more isolated. So, like you say, we go on Zoom, and go virtual — everything is personal and virtual now. People want personal computers, personal streaming, personal choices. We see — we actually believe this radical wearable transformation may come three or four years faster now because of the pandemic.

Zierler:

Oh. Mm hmm.

Fan:

And because of that — I think you already notice rapid changes in consumer behaviors; for instance, streaming. Alright? Streaming Netflix and streaming everything, all this digital information come to us much faster. Remote Zoom meetings!!! Streaming music in Apple AirPods!!! We will have personal devices on our bodies and have personal digital information delivery to us. We will have a lot of personal wearable choices. All these come to us three or four years earlier. The trend is quite clear now. So, our company is doing much better, especially in the wearable area. We have always been strong in the defense industry. We are stronger now because defense is shifting to personal wearable computers and communicators on the soldiers, and to AR for the pilots. Our business is growing rapidly now, especially for the wearable and AR applications in military.

Zierler:

And John, have you been going into the office, or are you running things from your home, mostly?

Fan:

That’s interesting. I would say when the pandemic first started — of course, everybody got locked down. Then I started going back one or two days to the office. The last two or three weeks, I was told not to show up in the office again, because I’m essential, but not essential. [laughs] Our production line, our assembly line, everybody was at the facility, and they are essential to be there. The company decided that I can actually function much safer at home, from a home office. And they put a home office around me. So, I think it is more effective, certainly safer. This way, my time is more effectively used, and I don’t need to be in the office. However, I do miss the person-to-person interactions.

Zierler:

Right.

Fan:

In fact, we’re often thinking about radical innovation. I’m always thinking about innovation. What makes people innovate? Right? I think all of us in high tech want to encourage creativity and innovation, especially in a technology company like ours, we survive or thrive on innovation. This pandemic is interesting. I think the pandemic allows us to have more radical innovations, but we’ve slowed down cooperative innovations. So, we cannot physically work together. It requires a lot of cooperation and interaction for incremental innovation and for technology or product enhancements. That was slowed down. But as you stay home, you can think about something more radical. I think it’s because you’re not confused, or even — even actually distracted by your colleagues’ thinking. I always believe great innovations sometimes occur quite randomly. Some people would say: oh, let’s go innovate. Innovation on demand. Perhaps for incremental innovation, one may organize or even demand for such goal. Radical innovation however often comes about from out of the box thinking. The pandemic may encourage such radical thinking more, being alone and isolated in your thinking.

Zierler:

And John, as a technology company, as a leader of innovation, correct me if I’m wrong, but Kopin has also demonstrated on the production line that people can be physically present and also safe. There haven’t been problems in terms of keeping up with the production line, keeping up with the laboratory work, and maintaining safety and social distance protocols at the same time.

Fan:

That’s a very interesting question. Our production line is in a cleanroom, like a Class 10, cleanroom. So, everybody has to gown up, go in there. and ventilation, as you will know, in a cleanroom, the air is circulated rapidly every second. And to enter clean room, you wear gloves, wear masks, and wear special boots. So, that itself is a safe environment. And many of our workers actually love to go in there. They feel safe. [laughs]

Zierler:

Yeah.

Fan:

They go into what they call an isolation chamber. And we also make the people spread out, so they don’t work closely together. We have a whole bunch of procedures that allow us to keep everybody safe.

Zierler:

So really, John, your company was quite well prepared for the pandemic, even before you knew it was coming.

Fan:

[laughs] Great comment. We did not know it was coming, but it happened we are in the right place at the right time. Yeah.

Zierler:

[laughs] Well, John, let’s take it all the way back to the beginning. Let’s first start with your parents. Tell me a little bit about them and where they’re from.

Fan:

My parents!! — I was born in Shanghai, China, near the end of second World War. It was so long ago. My parents were in China. My parents actually came from family that owned land and department stores in Shanghai. They were well off. But crazy things happened — after the second world war, we had the civil war. And the Chinese Civil War was really, in many ways, a class war. So, you have peasants against the merchants and landlords. So, my parents left China in the beginning of 1950. I believe it was in January 1950, just right after Shanghai changed hands. My wife always says that I was on the last train out of Shanghai. [laughs]We did leave on a train, not a boat. There was a book called Last Boat out of Shanghai. I don’t know whether you read it or not.

Zierler:

Yeah. Yeah.

Fan:

[laughs] But we were in the last train out of Shanghai. [laughs] So, we went from Shanghai on a train to Hong Kong. At that time, I was about 6 years old. And I still remember on the train, there were soldiers all around, guns and all, and my father had arranged that — each of his sons — we were three boys at that time, had a male employee with each of us, because if there were bombs coming around, and you had to escape the train. A lot of times, when you left the train and came back, you lost your kids. You didn’t know where the kids went.

Zierler:

Yeah.

Fan:

So, we each one of us had a male employee with us all the time, just in case we had to escape the train.

Zierler:

John, to go back to the war for a second: did your parents ever talk about how they fared during the Japanese occupation? Were they able to keep their business?

Fan:

Yeah. They didn’t talk too much about it. Obviously, they were not happy with the occupation. But having a department store — actually, our department store I believe was in the French concession area, so it was away from the Japanese occupation, until after Pearl Harbor and the Second World War came. Of course, then things did change. But at that time, there was a Chinese puppet government running it. So, he didn’t see too much change, and he was very happy to have the Second War ended. Then, of course, the Civil War came. Everything was lost. So, [laughs] it’s fair to say for years, he would not allow us to go to China, he was so mad about it. Yeah.

Zierler:

How would you describe your parents’ politics?

Fan:

I would say they were definitely anti-communist, of course, because they lost almost all their assets and had to start over again in Hong Kong. Land, holdings, family business and almost everything left behind. We went from a pretty well-off family to refugees, and then left almost all our relatives in China behind the Bamboo Curtain. So, I can understand their frustration, their anger. After a while, they seemed to calm down, and they allowed me to go to China. And now, I can go to China anytime I want. They also — I would say they’re, in many ways, quite liberal. My father passed away a couple of years ago at 98. My mother is over 100 now, still staying in Hong Kong.

Zierler:

Oh, wow.

Fan:

And I would say she’s liberal — her politics is very much like Massachusetts politics. [laughs] So, they’re liberal. They understand why at that time there was the Civil War in China.

Zierler:

John, do you have any memories of mainland China from your early childhood?

Fan:

Yeah. When I was in Shanghai, I remember bombs coming down, and I asked my mother. I said, “What is it? How come there’s people laying eggs?” I thought there were eggs coming down from the planes. [laughs] The plane, to me at that time, was like a bird, and then the eggs come out. And since we’re in a French concession area, we’re not bombed. It’s just I didn’t know what happened. Just eggs kept on coming down. [laughs]

Zierler:

What were your earliest impressions of Hong Kong? Did it feel like a new world to you?

Fan:

All I knew is that it was a new place. A very different place. I did not know then we actually left China. We left from the Canton area. Perhaps, near Shenzhen area to Hong Kong. I vaguely remembered I was searched by a Chinese soldier on the China side because refugees were not allowed to leave with valuables. They even searched the kids, maybe especially the kids. I had a gold pendant around my neck. The soldier patted me on the chest, and my mother was afraid he would find it. He didn’t. Later, my mother found the pendent by some chance, had swung to my back, and the soldier missed it. [laughs] The Hong Kong side, which was a bridge away, was wide open. Basically, people just walked right in at that time. And then when we went in there, I remember at that time, I was still very, very young. I didn’t know there was a big difference, except that everybody is crowding in, staying in a very tight space, because there were so many refugees flooding into Hong Kong. Yeah. So, I remember three or four households living together in a small apartment at that time. Yeah.

Zierler:

John, what was your earliest schooling like?

Fan:

I guess you want to touch every subject. [laughs] It was okay. I don’t know how much you know about China. China is a very big place. I think it’s probably bigger than Europe. So, there were so many languages and dialects. I came from Shanghai, with a Shanghainese dialect, and Hong Kong speaks a Cantonese dialect.

Zierler:

Right.

Fan:

And they’re as different as French from German. So, you walked into the school, and of course, everything was taught in Cantonese. I had no idea what they were talking about. So, I got zero in every subject. [laughs] So, that was the start. It was zero. And from this lowest point in school, one climbed up. Our family had some money sent out of China before we physically left China, so our parents actually were able to hire a private tutor, I believe she was actually my home room teacher to teach me how to speak Cantonese. Another interesting point in schooling, there was so much confusion, I believed I entered in first grade, or maybe even second grade. I was always among the youngest in my classes and graduated from high school at 16 years old.

Zierler:

And was this a private school you went to?

Fan:

Yes, at that time it was a private school.

Zierler:

And how much was English part of your world? Were there English signs? Was there English on the radio? When did you pick up English?

Fan:

That’s an interesting question. One of my private tutors spoke English. And my English name, John — John Fan — “John” was actually picked by her. My Chinese name is composed of three characters. The last character in Cantonese sounds like John. So, that’s how “John” came about. So, we actually learned a little English even in primary school, and my primary school was a private school, but was not a very good private school, because it was just a neighborhood school. Then I went to another school around Grade 6 or Grade 7. It was still a private school nearby. Remember, Hong Kong was flooded with refugees at that time and schools were very crowded and most kids went to neighborhood schools. And I was a very mediocre student until I was in Grade 7. In the British system, each grade was called form. Each of those forms, usually had one or two hundred students, breaking up smaller sections.

All of a sudden, I became number one in the whole form. From very low performance, like in the low quarter to number one. And I became number one because of my mastery of math and science. I didn’t know why, but all of a sudden, in Grade 7, I was very good in math and science. Before Grade 7, I actually was a very mediocre student. From there on, a year later, when I was to enter Grade 9, a government-sponsored English school picked me to enter that elite school. It was far away from my home. I commuted to that school on a slow tram every day, and it would take me over thirty minutes each way. It was very high standard and prestigious. It’s hard to describe why that school picked me. It was one of the few top schools in Hong Kong at that time.

And then from there, I went to Berkeley. So, it’s a very interesting kind of journey in my schooling in Hong Kong – started with near disaster, then ordinary, and finally to a top school. As I mentioned, I graduated with high honors from high school at age 16. But my parents did not want me to leave home and go to America so very young, so I went to college preparatory school till I reached 18 years old. In December 1961, I left for Berkeley and America right after my 18th December birthday. I left, this time on a large ship, one of the large ships of the US President Line. It took 18 days from Hong Kong to San Francisco. I still remember standing alone on the deck as the ship left the Hong Kong dock and seeing my parents fading away. Up to that time, I never had left my mother. I actually cried, which was very rare with me crying.

Zierler:

John, how did your father rebuild his career in Hong Kong?

Fan:

He used to run his large department store, a well-known one in Shanghai, other family businesses and other lines of businesses with his friends in Shanghai, but in Hong Kong he started a manufacturing factory, making cosmetics: toothpastes, face creams, lotions, and became quite successful.

Zierler:

Did he have an engineering background at all?

Fan:

No. No, he did not have an engineering background. In fact, he was a top high school student in Shanghai, but then his mother asked him to run the family business after his high school. His dream was to go to Oxford after high school. Oxford, Cambridge, U.K. And he could do that. He was one of the best students at that time. But his mother wanted him to leave school right after high school and take over the family business, because his father passed away years ago and his mother was running the business. So, his mother said: you take over the business. So, he became a businessman. But he had this dream; he’s always wanted to go to Oxford or Cambridge. So, when I graduated from Harvard, he was so happy that he flew specially for my Harvard graduation. He said, “You got the degree that I always wanted to get.” [laughs]

Zierler:

Ah. John, did your father ever hope, maybe privately, looking at your talents, that you would join him in his business?

Fan:

No. My younger brother went back to Hong Kong after he graduated from Berkeley and joined my father’s business. My father would not even let me stop studying— it’s interesting you ask. I think during my second year at Harvard, when I was doing graduate study and research, I actually wanted to drop out. So, I went to see my faculty advisor. I said, “I would like to stop studying for my degree and drop out.” And it’s different from Edwin Land, who dropped out of Harvard and started Polaroid. He dropped out because the professors said, “Edwin, you can leave Harvard now. We have nothing to teach you.” [laughs]

I wanted to drop out for a different reason: I felt that there were couple guys in my class who were so much better than I was. I graduated from Berkeley at the top of my class, but I was no longer top at Harvard. Okay? So, I told the professor. I said, “I can’t match this guy, and there’s no way I can match him.” I felt that I was not qualified. I should drop out. Well, that’s a very interesting revelation. The professor looked at me, and he said, “John, first of all, I know that guy. That student is very good. That probably happens once every several years that Harvard has a student like that. But the world needs a lot more people like you.” [laughs] Okay? “A lot more like you. And you have a different talent than he has. One thing I will let you know: everybody has a different talent. This particular guy” — I will not mention his name; he actually became a pretty well-known professor at Harvard later— “is very detail-minded. He does everything in great details. So, he’s very logical, methodical. And we do need people like him. You’re different. You’re more global. You see things differently, and the world needs people like you, too. So, everybody has a different talent. We want you to stay.” I also went to ask my father, and he absolutely wanted me to stay. He said, “No. You’ve got to finish this degree.” Remember, I had an all-paid fellowship from Harvard for five years, so it’s not like there’s any tuition fees issue anyway. I just felt I was not good enough. That guy was just too good. [laughs]

Zierler:

This must have been a very important life lesson for you, what this advisor told you.

Fan:

Oh, yeah. That advisor later became very well-known. He left Harvard later and joined Stanford in the west coast. His insight was correct. Of course, there was the hindsight, and he was right. All through my life, I’ve met many, many smart people. Some became very well known, some got the Nobel Prizes. And our company also has a lot of smart people. I find that each one of them is different. And since I’ve been around long enough, after 20 or 30 years, to see these smart folks develop, each one of them had their own way of success, in many ways reflective of their innate talents. Some people see things extremely detailed, [laughs] like a chess player. You know, a chess player. And I just saw a good movie on Netflix on a chess player recently, I assume you had too. [laughs]

Zierler:

Yeah.

Fan:

And those folks follow formulas and rules. There are some basic rules given to them. They can see steps -- many steps -- ahead of you. And these folks could become very, very good IC process developers. They could improve and develop new IC processing and find methods to shrink a transistor into smaller and smaller transistor. They would be perfect, absolutely perfect, because they know the rules. They are very good in what I call “incremental” innovators. They know the process steps and rules. But we also need other types of guys —who develop something without any rules. You have to create your own rules. Okay? Those are the radical innovators, while the earlier type of folks are incremental innovators. Let’s look at the guy [Elon] Musk of Tesla. Electric car, there are no rules. If one looks realistically at the situation then, you would never start and build a company to do electric cars at that time. Everything tells you it would not work. The cost, the battery, a hundred different things wrong with the idea. But you need guys who do not follow rules. Musk probably is not a good chess player.

Zierler:

It takes all kinds.

Fan:

I mean, that’s civilization. That’s why humans are humans. We each is wired a bit differently, and each of us is valuable. I always say: every person has virtues in their own way — and some of my best inventions comes from technicians.

Zierler:

John, was your decision in high school to pursue higher education outside of Hong Kong — how much of that was about the limitations of the educational system in Hong Kong, and how much was it about your desire to go out and see the bigger world?

Fan:

That, I’d have to go back to our Asian culture. Asian culture in those days, when you’re young, when we’re kids, your future actually was mapped by your parents, and also mapped by— in many ways, your social class, by your parents’, class. If a kid in the social class goes overseas, then he in the same class also goes overseas. And at that time, in Hong Kong, the kids in a well-to-do family — at that time, we had become reasonably well-to-do --you really had only two places to go. One was to go to England, U.K. And the people who went there, planned to come back to Hong Kong after graduation, and to help to run Hong Kong — to help the British run Hong Kong. Another group of people would send the kids to America, and those were the kids who went there — the parents did not want them to come back. Okay? You go there, and you find your future. There’s no future in Hong Kong — no long-term future. Well, my father belonged to the second group, because he escaped from Shanghai. He always felt Hong Kong was only his transit base. It’s not home, and he always was concerned that communist China could enter Hong Kong at any moment.

Zierler:

Yeah.

Fan:

So, my parents would like us to go to America. So, you see, there were two different groups. One group, the kids went to the U.K. The other group of kids went to the United States. So, I didn’t have any choice. I never thought about it. It was picked by my father. My older brother already, at that time, was studying at Berkeley. So, it was automatic I would go to Berkeley joining him. So, I’ll just follow him to Berkeley. Yeah.

Zierler:

So, it was really more about Berkeley specifically, and not about the United States generally, for you.

Fan:

Even Berkeley, I did not know Berkeley or how great the University was. It was just a school that my brother was attending.

Zierler:

Yeah.

Fan:

He was in Berkeley. He could have been in a junior college, and I would follow him to it. [laughs] As long as they let me in at the time. Berkeley let me in, and he was there. Hey, it appeared to be fine. You know, I didn’t know Berkeley from any other school. So, I just went there, and it turned out to be a very, very good school at that time and I had an excellent experience there. And even now, Berkeley is still a very good school.

Zierler:

John, what was your first year? What year was it when you arrived in California?

Fan:

Late, I believe near end of December, just after my 18th birthday, 1961.

Zierler:

1961.

Fan:

Yeah, because when I applied, I was late. I entered the spring semester, ’62 spring semester. Yeah.

Zierler:

What were your impressions of Berkeley and northern California?

Fan:

Wonderful place. Extremely modern. I had often made comments, later on, about what my first impression about the big contrast — when I arrived at Boston, Harvard campus years later. Everything at Berkeley and California in the early ’60s was so new. Everybody was so upbeat and friendly. This was the golden age of America, certainly of California — ’60s. And the school was very good, very open. Shockingly open. Berkeley, at that time, was very open.

Zierler:

Were there many Asian students at that point? Were you one of the few?

Fan:

Yeah, one of the few from Asia. Those days at Berkeley were very white. And I was an electrical engineering major, so there were also very few women. [laughs] It was a very interesting school, and very liberal — in some of the areas, too liberal, for people, especially for kids like me who came from Hong Kong, which at that time was conservative and reserved. I stayed in a dorm, and I couldn’t believe what was going on in the dorm. I didn’t understand it. My roommate sometimes kicked me out and said, “Don’t come back for a few hours.” I’d have to leave the room for a while. [laughs] So, that was kind of strange for us, behaviors that were not understood well by Hong Kong students. But after a year or so, you learned very quickly. [laughs] You became more liberal, and more assimilated. I mean, you went to some of the mixers, but you had to be very careful. All those drinks were spiked.

Zierler:

Yeah. John, how focused were your educational interests when you started at Berkeley? Did you know pretty specifically what you wanted to pursue, or were you open to a wide variety of areas of education?

Fan:

See, I always liked history and social science topics. In fact, when I graduated from high school in Hong Kong, at that time, I was very good in history subjects, literature, and my school principal actually called my mother to say: your child should be in history or liberal arts. And my mother said, “History? What can you do with history afterwards?” And even the school principal couldn’t answer that. So, when I applied at Berkeley, I picked electrical engineering. [laughs] Why do you pick electrical engineering? At that time, the best students usually picked either engineering or physics. Today, the best students may pick life science. Right? Or business, or economics. But at that time, at least a lot of Hong Kong students picked engineering or physics.

Zierler:

John, what kind of exposure did you have to laboratory work as an undergraduate?

Fan:

A lot. I’m not the world’s best lab guy. Adequate. In fact, when I graduated from Harvard to work at MIT— in fact, part of my thesis was also done at MIT. I had a kind of joint thesis: half at MIT, and half at Harvard. I already knew I’m not the best guy with my hands, so MIT Lincoln Laboratory, when I joined, hired technicians to do experiments for me. [laughs] So, to answer your questions, I was aware of what’s going on in the laboratory, but hands-on experiments were mostly done by my technical assistants. In fact, in the early days, some of my inventions happened because of accidents or mishaps by the technical assistants. They made a mistake, and something strange happened, and I would look at it and then figure out why, and then it’s from “why” to “how,” and then actually to innovations and patents. But I’m not very good at actual running the experiment. So, I’d need assistants to run the experiment, hopefully make some mistakes, [laughs] so I could see the mistakes. So, many of my important inventions were caused by some accidental mistakes.

Zierler:

Yes.

Fan:

I loved to look at the unexpected results and try to figure out why: what’s actually going on? What’s going on? And then from there, come out with new concepts and perhaps even new inventions.

Zierler:

John, what did you do during your summers as an undergraduate? Did you go back to Hong Kong? Did you stay at Berkeley for labs? Did you go see the rest of the country?

Fan:

What a question, David. What a question. When I came to Berkeley joining the spring semester, I remember after six months, we had the first summer. The first summer (and the second summer also) I went to Lake Tahoe and became a busboy in a Swiss restaurant. It was a beautiful experience. A beautiful experience. You bussed the dishes and chatted with the customers and learnt quickly English (or rather US oral language). I was still young at that time. At nighttime, the waitresses would sneak me into the casinos. I remember I was not allowed to get in, but they sneaked me in because I was underage. So, those were very interesting days, and you learnt a lot of things. The third summer, you would not believe me. I became a door-to-door salesman. So, I sold encyclopedias all over the western United States. We traveled about 10,000 miles. We’d go town to town — went from town to town, selling encyclopedias, door-to-door. And I never told my father that one. The first two summers, I told him what I did, that busboy job — this travelling salesman job I didn’t. He would have never allowed that. But at the end of that summer, we made enough money to pay for the summer experiences including the extensive traveling expenses. I enjoyed touring all western parts of the country, especially the remote rural areas. Of course, also allowed me to learn the door-to-door sales technique.

Zierler:

Right. That served you well later on.

Fan:

Oh, yeah. How do you get invited inside people’s homes? How does one get folks to sign the sales contract? How to make sure they don’t back off? And remember, my English was still not very good. At that time, many of the small towns in Idaho or Washington State, they’d never seen Chinese before. All of a sudden, this Chinese kid was running around. I actually was sometimes stopped by the police. They said, “What are you doing here kid?” Once they knew I’m a college kid, they let me go. [laughs]

Zierler:

Right. [laughs]

Fan:

But again, that’s an extreme experience. Why did I do that? I wanted to have different experiences. The fourth summer, I went to IBM.

Zierler:

Ah.

Fan:

IBM in San Jose had a development lab — developed concepts of new products. And that product at that time was being developed by an IBM Fellow. I don’t know how much you know about IBM Fellow, which they got money from IBM to develop anything you wish to. At that time in the mid-60s, IBM was like Apple today. The number one tech company in the world, and there was abundant funding for new product concepts.

Zierler:

Sure.

Fan:

That IBM fellow — I remember his last name was Johnson — he developed the video tape recorder. VCR. It’s a huge, almost half the room size. But it worked — you could videotape everything. And IBM stopped producing this innovation. They said: we should not commercialize this — because it’s not our core business. I think that the technology was taken out to a startup called AMPEX. I am not too sure about this though. Eventually, VCR business turned huge and was pioneered by Japan companies.

Zierler:

I’ve heard of it.

Fan:

Yeah. It was a wonderful invention that Johnson did, but it was against IBM’s core business. I was a summer intern in his team, and I learnt the process of inventing a very complex electronic device. [laughs] So, the fifth summer, I went to IBM Thomas Watson Laboratory in New York State.

Zierler:

Sure.

Fan:

Yeah. And at Watson Laboratory, my IBM team were examining — I still remember, the physics behind microwave oscillations in germanium crystal. So, crazy me at that time, after just a few weeks at my summer intern job, I decided to and I developed a whole mathematical theory to explain that interesting oscillation phenomenon. And remember I was just a first-year graduate student. Right? Summer student. And I asked for a meeting and started to describe my model to a bunch of super smart IBM scientists in the team. I explained my theory, and those guys looked at it, those scientists, and within 15 minutes, they said I violated some of the rules. And then it was basically the end of my scientific credibility with them. [laughs] I still worked through the whole summer, but they never really talked to me much after that. However, when I went to MIT Lincoln Laboratory after I graduated, the guy who was my IBM boss at that time complained that I never applied for a job at IBM when I later graduated from Harvard. I was kind of basically brushed off after that disaster for the rest of my summer intern tenure. [laughs] And to this day, I still think my theory may be correct. [laughs]

Zierler:

Ah.

Fan:

But I think that they were just stunned by this little kid, that thinks that he developed a new theory. [laughs] So, that was my interesting IBM experience. After that, when I graduated, I went to MIT Lincoln laboratory, another top science laboratory in the world. I felt MIT people were more open at that time.

Zierler:

John, did you realize that you liked being in an industrial research environment, even as an undergraduate, for the summer experiences at IBM? Did you feel at home in that kind of a place, and see long-term that that’s where you might make a career for yourself?

Fan:

It’s very interesting. IBM at that time — maybe at that time, there were about four or five famous labs. Bell Labs, obviously, was number one. I believe the second one may be IBM Thomas Watson Laboratory. Lincoln Laboratory maybe third, at that time, the Xerox Palo Alto lab was also up in the top list. The Xerox lab was very, very good. And these were top labs. In many ways, they are better than academic labs. So, when one graduated at that time— either you joined academic universities, but if you wanted to do some wonderful work with abundant funding, these were the four labs to join. Besides, again, there was — maybe there was a feeling at that time, that said: if you go to those labs and worked about 5, 6, 10 years, you could have a lot of publications.

And then, those top universities — say Harvard or MIT — they would come to you immediately and give you a tenured position without one having to fight through the assistant professor track. You do not have to teach, and to fight for external funding — it would be quite a mess. Therefore, if you’re good enough, go for these top labs, and if they hire you, you go in there, you already have all the funding, because those labs have a lot of funding. When I graduated, I went to Lincoln Lab for the first three or four years. They would not tell me what to do. They just gave you funding. You pretty much did anything you wanted. Anything you wanted, and they provided you with technicians and everything. There’s no academic lab that can match that. So, you just had to be able to get in. [laughs]

Zierler:

Right.

Fan:

And then you’d create — you’d write a lot of papers. I wrote a lot of papers those days, as you well know. I had hundreds of papers. And if I wanted — which, at that time, if I didn’t start the company, most likely a university would come around and say: John, come and join us, with your papers and books. We’ll give you a tenured position, of course. Right? So, you don’t have to go through this difficult tenure track, starting from scratch.

Zierler:

Right.

Fan:

So, yeah. There were maybe four or five, those wonderful, special labs in this country at that time. Maybe the top in the world, actually. Unfortunately, it is different right now.

Zierler:

John, I would like to ask. When you were starting to think about graduate school, many international students who come to the United States, they have a decision point right about that time, as a junior or a senior, when they’re thinking about graduate school. And that decision point is: am I going to go home, or if I go to graduate school, does that mean that I’m making a life for myself, and I’m here in the United States permanently? I wonder, for you, given how you talked about your father’s advice and expectations, and thinking about Hong Kong, not as home but as a starting-off point, was that decision for you more or less made simply by going to Berkeley, and by the time you were thinking about graduate school, you had already committed to becoming an American and making a life for yourself here?

Fan:

Yeah. David, that’s a very good question. Of course, you’re going back many, many decades ago. When I was finishing up at Berkeley, at that time, at Berkeley, I was one of the best students they had. Okay? So, the professors at the electrical engineering department already said, “John, we want you to stay.” Interestingly at that time, the Berkeley electrical engineering department, in particular, did not encourage their own undergraduate students to stay for graduate school. They actually wanted students to go somewhere else for graduate studies.

Zierler:

Yeah.

Fan:

Except in rare cases. The department did make me into a rare case, and shockingly, they provided me a Regents’ fellowship (a great honor provided by the whole University of California System), which was four- or five-year all expenses paid fellowship, to stay for the graduate school. Now, there was never, in my mind, going back home anyway. Hong Kong had been a trade and financial center. It was not famous for academic or technology research. So, you as an engineer or scientist had no place to return. You couldn’t go back to China, because your family escaped from there. So, it’s pretty much given that I would stay at Berkeley for graduate school.

But then one of my favorite Berkeley engineering professors— he actually was a graduate of Harvard’s applied physics department, and he brought me over to his office. He said, “John, I have to ask you a very honest question.” I said, “Yeah?” “What is your intention after you graduate from graduate school?” I said, “I want to stay and work in California.” It’s beautiful weather and people. He immediately stressed “So, if you want to stay in west coast after you graduate from grad school, then I advise you to go to the east coast.” I said, “East coast? I’ve never been there. [laughs] I’ve been in the whole western part of the United States when I was an encyclopedia salesman, but never had crossed the Rockies.” As far as I’m concerned, east could be Australia. Okay? [laughs] I didn’t get it. He said, “Yeah, and I think you should go to Harvard.” I said, “Why?” He said, “The east coast and west coast are very different.”

Zierler:

Right.

Fan:

He continued “Very different. Different cultures, different way of looking at things. If you ever want to come back and stay on the west coast, you’ve got to go to the east coast. Okay? And I think you’re good enough to go to Harvard.” I said, “Harvard? I have no idea what you mean by going to Harvard.” So, he helped me to apply. And Harvard, at that time — there was a test called GRE or whatever, the graduate school application exam. Berkeley didn’t even ask me to take it, because they just gave me the fellowship. So, I never took the test. But by Harvard requirements — you have to take that test. No time now, because it was a kind of sudden decision that I wanted to go to Harvard. But they made an exception and gave me a five-year University fellowship, tuition and expenses all paid. So now, I had a choice: either go to the east coast or stay in the west coast — and I decided to go to the east coast as my professor advised. To this day, I do not fully understand why I decided to leave Berkeley. My brothers, who were then at Berkeley too, and my friends were all in California. Perhaps, it was my desire to explore unknowns or to get new experiences. I never, ever had visited Harvard before I decided. [laughs] That first day was when — my first day I arrived at Harvard, and I always told people that I almost wanted to go back. I said, “This place is so ugly. Harvard looks like a factory, and Berkeley is so beautiful. I’m going home.” Back to the City by the Gate. [laughs] So, my first Harvard impression was, “Ha! What an ugly campus compared to Berkeley.” [laughs]

Zierler:

What do you think was behind your professor’s advice? Why did he — it was obviously in his interest for you to stay at Berkeley, so what do you think was behind his advice for encouraging you to go branch out and pursue a degree at Harvard?

Fan:

Well, that professor has a British background. He came from England. He went to Harvard. He got his Ph.D. at Harvard and then came to Berkeley as a professor. I think at that time, just like that Harvard professor I mentioned earlier, those professors might look at their best students really differently. They thought themselves as mentors, the mentors of students. Now, maybe not to all their students, but certainly to some of their better students, I’m sure they consider me as one they want to cultivate in their own image, in some way — in their own image. So, for this professor, he was an immigrant to this country from England. He went to Harvard and then to Berkeley, so he has the east-west USA and British background. I’m from Hong Kong, which is English in some way, and the west coast. He actually wanted me to have the east coast background. And he obviously felt that I could do well any place anyway. And Berkeley would want me back. So, yeah. Why don’t you get that east coast experience and come back? So, in some ways, he’s still thinking about Berkeley. As an aside, I never moved back to the west coast. The best plan got ruined. I married my wife in my last year of graduate school. She was born in Boston and raised in Boston’s Chinatown. She made clear that she wanted to say around Boston. I do not regret that I decided to stay in Boston and to start my working career at MIT Lincoln Laboratory.

Zierler:

And this was the EE department at Harvard that you joined for graduate school?

Fan:

Harvard had no EE department at that time. They had applied physics and general engineering at that time, so I joined the division of applied physics and engineering and later got my doctoral degree in Applied Physics.

Zierler:

But that’s just the name. The curriculum was more or less similar to other EE programs.

Fan:

Ah, yes and no. I think they’re more fundamental. They taught you more fundamental theories, more physics, more material sciences. So, they’re more physics-like than engineering-like. Yeah.

Zierler:

Did you enjoy that? Was that useful for you, to have that stronger physics background?

Fan:

I think so. This is hard to say. If I had stayed at Berkeley, I probably would be on a different track. I might be doing more engineering-like, such as semiconductor development, process development, than trying to create something — trying to radically change something. At that time, at Harvard, everybody was thinking about radically changing things. It’s a very different philosophy.

Zierler:

What were some of the most exciting opportunities, technologically and scientifically, at that time?

Fan:

At that time, in the Boston area in the early 1970s, there were a couple of very, very interesting tech companies around Route 128. Boston was very prominent in having quite a few very successful tech companies at that time. Remember Digital Equipment, Wang Electronics, Data General, Polaroid — and we, as grad students, were worshipping those companies. And those companies — they’re startups, actually, spectacular startups. The Digital startup was from MIT Lincoln Lab. Ken Olsen, the founder, came from Lincoln Lab. And when I went to MIT Lincoln Lab in 1972, one of the big stories many of my new colleagues related — they told me stories that they were invited to join Digital when it started and most refused to join. By the time I joined Lincoln — Digital had already been started about four or five years before I joined Lincoln. They said they thought the new minicomputer developed at Lincoln Lab by Ken Oslen’s team, called PDP, a small to medium-sized computer was for some military or space applications.

But Ken thought the computer could be used for businesses especially in smaller facilities or small companies instead of having central IBM computers in large control rooms, like the huge IBM-360. So, he started Digital, and many of his Lincoln colleagues thought nobody’s going to want small computers or medium-sized computers. So, they refused to join him. And of course, five years later they regretted that they did not join. It was a well-repeated story at Lincoln when I joined. Right? And Wang had a similar story. He created these word processors and calculators, which were very different, radical and first of its kind. Like Ken Olsen, An Wang was going after IBM centralized approach. An Wang got his doctorate at the Applied Physis Department at Harvard, same as mine, though years earlier. And then Polaroid, of course, invented the instant camera. But you look at all these, they were radical changes. They’re not incremental changes. Digital radically changed from big, centralized computer systems into more distributed systems. Polaroid instant camera was so different from regular Kodak film camera. Very different. Word processing. Wang created word processing. So, we all were looking up at them, wishing, we could change people’s lives too.

Zierler:

Yeah.

Fan:

So, when I went to Lincoln Lab, the first two, three things I did — remember, you could do almost anything. You could do pretty much anything you wanted.

Zierler:

Yeah.

Fan:

I could do anything. I wanted to save energy at that time. It was early 1970s, there was a serious energy crisis in the world. So, energy conservation was hot. I created a special coating on the windows panes to conserve heat. We put what I called transparent heat mirror coatings on window glass panes, and I calculated and proposed if we put argon gas or nitrogen gas between glass panes to reduce the heat convection current, these windows would have very good heat insulating properties. After all the years, people are still doing just that, though better. MIT patented my invention and MIT licensed it to folks. And so, that was one of my first inventions when I joined MIT, inventing thermal windows which people now are using.

There is a real interesting side story. Many years ago, my wife and I were shopping for thermal insulation windows for our first house. There was this salesman pitching to us these wonderful insulating windows that had these special coatings invented at MIT. You may have read that story that I had told a Harvard writer who interviewed me about my early invention. My wife said “Well, maybe you are looking at the guy who invented it.” I mean, at that time I looked like a graduate student, actually. We never thought the salesman believed what she said [laughs]

So, yeah. It was in fact an accidental invention. A technician made a mistake. I figured out how this mistake was made and why it worked, and how to use to heat insulate windows. I went on researching and inventing other things, such as solar cells for space and terrestrial applications. And then, one day, I said, well, if people can splice different genes together and can reduce the rejection phenomena, we should be able to put very different materials together. At that time, traditional material science taught us if one joined materials having different atomic structures, they rejected just like in genes and the combined materials would be full of defects and become useless. However, we believed we could develop techniques to suppress the rejection phenomena. We decided to splice materials together and created a new field we called wafer engineering. We would splice optical material with electronic material, or we would actually make material combination composites, which could not happen in nature. And all you had to do was to figure out: how to fool the atomic structures and stop the rejection. Basically, fool the materials and make them match. And that’s how we started the field at MIT Lincoln: saying, “Let’s fool them.” And after a while, we’ve become very well-known.

People began to encourage us to spin out. They became interested to invest in us. At that time, I honestly told them: I have no real business plan. I didn’t know what the new technology could be used for. We didn’t know. They said, no problem. Just come out. And we negotiated and got about 30 patents licensed from MIT, and then started the company. [laughs]

Zierler:

John, who was your graduate advisor at Harvard, and how did the connection with MIT originally come up?

Fan:

Yeah. My graduate professor was Bill Paul, who actually also came from England, and then became a Harvard professor in Applied Physics. He’s a materials scientist. My thesis was very interesting. It was a material called vanadium oxide. And at that time, it was found that vanadium oxide was a compound that switched from an insulator to a metal, at a temperature around 65°C. An abrupt transition in electrical conductivity. So, we thought these materials that switch like that, from insulator to metal, could be an electronic switch. If so, we can use that phenomenon to make a very fast computer, 0 and 1, 0 and 1. So, my thesis was, in fact, examining this compound: how to make it, how to grow its crystals and thin films and measure the optical properties, electrical properties. And, in some way, it was a failed thesis. This thesis concluded the transition is not an electronic switching. It’s a thermal switch. Now, a thermal switch is, by nature, slow to be used as an electronic switch for computers. Therefore, the thesis results were— I made the material, made the thin film, and measured it. I said: sorry, it is not electronic. It’s thermal. Okay? But they still gave me the doctoral degree— the thesis passed the doctoral committee. [laughs] I didn’t have to start over again.

And Harvard actually published my doctoral thesis for their own libraries and all, 350 copies of my thesis. And 10 years later, when I was at MIT Lincoln, I tried to get additional copies from the Harvard library, and they’re gone. All gone. And I wondered: why would anybody want to read something that failed, in some way? It’s thermal. Still, many years later, about 15 years earlier from today, I found out people had used this material to make thermal sensors, infrared sensors, for military and for commercial applications. It’s even more popular now.

And in fact, a few months ago, I received this Berkeley engineering journal. A couple of the professors at Berkeley electrical engineering department were raving about vanadium oxide, and how useful they are. And my wife — who, edited and typed the thesis for me, my Ph.D. thesis — she said, “Those guys never referred to you.” I said, “It’s okay. It’s okay. It’s Berkeley.” So, this turned out to be a very useful material as thermal sensor, so that’s why I say, in engineering or physics, a failure could be a success, for different reasons. Mine was a failure. It was not meant to be an electronic switch to be used in a computer. It turned out to be a thermal switch for thermal sensors.

Zierler:

But I’m sure this impressed upon you the importance of basic science.

Fan:

Yeah.

Zierler:

Just learning for the sake of learning.

Fan:

You study the material, publish the results, and the people learn about the material, and there’s some people who may find an application out of it. That may be the difference between Harvard and maybe with some other engineering school. Harvard is engineering, but not engineering.

Zierler:

Right. John, as you completed your Ph.D. and you were thinking about your career prospects and your professional identity, to what extent were you thinking about the world of business and inventions and patents? Was that part of your consideration at that point?

Fan:

Patents, definitely. Interesting situation at that time at MIT was that when you had patents, they not only gave you incentive to patent them, they shared a third of the royalties with you — with the inventors. This sharing and encouragement were very innovative at that time. So therefore, scientists like myself, or engineers like myself, had a lot of incentive to patent new ideas and findings, and to commercialize them in some way, or license them in some way, and get rewards for them. So, yeah, But Harvard at that time was different. They did not encourage the professors to start companies, because starting companies with ideas or inventions created at the university — in many ways, in Harvard’s thinking at that time were conflicts of interest. They were more pure. Right? There’s a conflict there. But MIT did not think so. They thought it’s a duty that when you invented something — that you should want to commercialize it, if you can. Either you do it, or you license somebody to do it, to make use of it. So, yeah. We were doing a lot of patenting, publishing, and we would license. And I was involved in encouraging companies to license. The coating for the windows, not only did MIT license it to other people, but also licensed to a lightbulb company to put the energy saving coating inside a lightbulb — an energy saving incandescent lightbulb. And the lightbulb actually worked quite well so I became well-known because of that. Those days were different, and scientists were so well respected.

After we started Kopin — The Wall Street Journal called me almost every month. Kopin was very high profile – MIT, Harvard, and Venrock. Top billing. Our Kopin laboratory grand opening was officiated by Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis and MIT Lincoln Lab Director Walt Morrow. Wall Street Journal reporter would ask “Okay, John. Is there any new stuff? Is there any new stuff?” It’s different from today, of course, but those were very exciting times. I mean, very productive time. Within a dozen years at Lincoln Lab and later at Kopin — I wrote around 200 papers. I almost wrote a paper every month.

Zierler:

Did you see yourself more on an academic track at that point? Ultimately, after postdoctoral research, did you think you ultimately would become a professor in an applied physics department or an EE department?

Fan:

Yeah. Some academic institutions had already started talking to me. It seems to be the logical track. When I was at Berkeley, my professor advised me -- “you go to Harvard. You can come back to Berkeley, or you go to one of those big labs and spend a few years, and come back to Berkeley or Stanford”. So, yeah. It was the track that he followed, and he felt that I should follow the same path, basically, until the Rockefeller people Venrock (the Venture Capital entity of the Rockefeller family) -- came and funded us to start Kopin.

Zierler:

And that was it.

Fan:

Then — yeah. Well, my father was an entrepreneur. Remember, he started companies in Shanghai, and in Hong Kong. So, you always have that entrepreneurial urge — you know, in the back of your mind,— I always admired An Wang, who started Wang Electronics, Ken Olsen who started Digital Equipment, and Edwin Land who started Polaroid — they all came from Harvard or MIT in those days. So, those were the people you looked up to.

At that time, there was no Steve Jobs to worship. [laughs] But we had those incredible guys. Those were the guys we worshipped at our age. And you always, in the back of your mind, hoped to do a little bit like them. Yeah.

Zierler:

John, I’m curious. At Lincoln Laboratory, either from grants from the Department of Defense or NSF or Congress, what did you learn about working with the United States government during those years?

Fan:

Those years were the golden years. There were government funds given to Lincoln that almost had no strings attached. Okay? And at that time, I think Bell Labs was like that. I’m sure Xerox Lab and IBM Watson Lab were pretty much like that. There were some oversights but very loose oversights. And that’s where great inventions occurred. Now, most of those labs have become much more applied-oriented, goal-oriented. And so, they now pretty much say: I want you to go from A to B. Those days, there’s no A and B. You were just told, “go West,” basically.

Zierler:

Right.

Fan:

“Go West, young man.” And they’d go west. You’d pick your own path and make your own mistakes, pick yourself up and make another mistake. But that’s really — it was America’s golden age. We don’t have it now.

Zierler:

That’s right.

Fan:

Yeah. I don’t know how we can get it back. That’s a sad story, I say. I don’t know how your readers are going to take it. It’s not a criticism. It’s just what happened.

Zierler:

Well ironically, John, so much of that support from the government in basic science, that’s now happening in China.

Fan:

Yeah. China — I don’t know now, but a few years ago, it was like that They would say: I’ll give you funding, and you do what you do. And the people do real innovative things. Some of them may go a bit too far. But we, I think in the spirit of protecting the taxpayer money or your company’s money, you want them to — “Show me what you’re going to do. So, tell me where it’s going, because I have to justify it to my investors or my shareholders.” Well, yes and no. [laughs] You’re not going to find true radical things. I mean, there is — Steve Jobs. Obviously, he was an idol for many of us. He’d say when developing your new consumer products —conventional business school teachings would say: okay, do a market study to see what the consumers want. Steve Jobs [laughs] said: if you want a radical consumer product, don’t ask the consumers. They don’t even know such a product exist. You ask them, and you will never get a radical product. It sounds so radical, but if you sit down and consider what he said — and I truly agree with him. We have had similar situations going on, in the wearable area, alright? You would wear computers or smart phones on your head, and you think that would be the next radical transformation. And 80, 90 percent of the people say Wow. This would be great. Hollywood also made crazy scenes to seduce you. However, if you sit back and say: is this really the consumers would want and accept? [laughs] But it’s hard to argue because it is seductive. Hollywood did a great job. Right? 80 percent of the people thinking they would like that way. But in truth, that might be the wrong way, or at very least too early, technology is just not ready or mature enough.

Zierler:

John, I want to ask. As you make this fateful decision to jump in with both feet and start Kopin — if you can set the stage as you’re starting to realize what a tremendously complex endeavor this is about to be — the personnel, the technology, the payroll, the regulations, all of these things — perhaps as you’re lying awake in bed at night, wondering how you’re going to make this happen — in reflecting on those early years, what are some of the things that you thought were going to be very difficult that turned out to be easy? And what were some of the things that you thought were easy that turned out to be difficult?

Fan:

That’s an excellent question that takes probably forever to answer. But I can only give you some episodes. Maybe the episodes demonstrate what happened. The first thing that happened -- I was leading a lab, a material lab. Part of our group was working on nanotechnology, which was to splice different materials together while reducing the inherent reductions resulting from different crystalline structures of different materials. Part of my group were doing other things. We decided to focus on wafer engineering in the new start up. Also, our investors interest was in the nanotechnology part. So, I selected out of my whole group of maybe 30 to 40 people only eight people to join me. And, I told the lab about who they were — later on replaced all of the eight people I took out before I left. The investor groups were composed of three VCs at that time led by Venrock, the venture arm of Rockefeller families. Venrock actually were the first investor in Apple, a few years before they invested in Kopin. And Venrock also invested in Genetech. At that time, Venrock was one of the top VCs in the country.

And they’d just say: John, we’d love for you to come out with your team members, technologies and patents. We’d like you to be the CTO, because you’ve run a technology group, but you’ve never run a business. You never went to business school, let alone to lead a tech company. And there’s no indication in your life that you’d know how to run a business. I don’t know whether it’s because I was just being too cocky or what. I said: well, I know I’ve never run a business. My father ran a business, though of course I was never involved in his business. But why should I leave MIT? I will stay at Lincoln Lab. I’m on top of the world. I have a big lab. I could be an academic professor. CTO is basically the same position. I’m in a great laboratory. I’m not leaving unless I am the CEO. Alright? But to be honest, at that time, Asians in those days of mid 1980s were never famous for running a company – An Wang was a rare exception, but he started his company without venture capitalists.

Zierler:

Yeah.

Fan:

In fact, during that time period, at MIT Lincoln Lab, or at IBM, Bell Labs, they all said: oh yeah, those Asian guys may someday become pretty good technical managers but no way they can run anything relating to business. They can’t become a general manager. They may eventually be technical managers. Okay? When I joined MIT Lincoln Lab, the first thing we found was — you would be shocked. Lincoln Lab, at that time, had about 2,000 people. There was never a single manager who was Asian. Okay? A lot of Asian engineers, but none ever became a manager. So, I together with other Asian engineers at the lab immediately circulated — remember I was from Berkeley, so I was radical — we circulated a petition and sent to MIT’s president and stated: do you recognize the whole lab has no Asian manager, actually never. To his and MIT’s credits, he acknowledged our findings. He at once promoted one: a library manager. The library — MIT Lincoln Library now had a first manager who’s Asian. [laughs]

Zierler:

[laughs] It’s a start.

Fan:

And it’s a woman, too. [laughs] It’s a woman. But soon, more and more Asian managers — but at that time, just technical managers. Well, I later did become one of their group technical managers. Our petition worked, I guess. Back to Kopin, Venture capitalists just couldn’t figure out there could be a company, sponsored by them, being run by an Asian. However, Venrock was open-minded enough, and perhaps my background of Harvard and MIT did not hurt. So, they actually promised to consider me as the CEO, and gave me an oral test. A bunch of their senior partners gave me an oral test, like a doctoral degree oral test. And they asked all these business questions. Of course, I had no real answers. I just made up the answers on the spot. But after two hours, they said: stop, stop, stop. We’ll try you. But please be aware that the average tenure of a CEO at our sponsored companies was 18 months. They usually do not last more than 18 months. I said, okay. Guess what? I don’t need any employment contract.

Zierler:

Yeah.

Fan:

Okay!!! I said if you guys decide I’m not good enough, I’m done. It’s okay. I don’t need any employment contract. Of course, at that time, Lincoln already told me: the minute you want to come back, come back. [laughs] I’d never imagined that after all these years, decades really, I’m still the CEO.

Zierler:

Right.

Fan:

Can you imagine? There’s a Harvard business professor who was our keynote speaker at our 30th anniversary celebration party. He actually searched through the history. He said: let’s look at the history of technology companies. How many technology companies are still here after they started, 30 years later? Very few.

How many technology companies that are still here and still have the same CEO and founder? The professor said he could not find any other. Steve Job was one, but even he was pushed out for a few years before he came back to Apple. You have been a CEO continuously all these decades.

Zierler:

Just you.

Fan:

Yeah. The professor said, “John, you’re a unique beast.” Right? “And your company is a public-listed company.” It’s not like a small, little company on the road side. It’s a public company with market cap going up and down, up and down, and it’s become very well-known in the late 1990s, with a market cap close to $3 billion. But somehow, the shareholders and the board kept you. So, we don’t understand. At the end, maybe we’ll have to do a case study on this. [laughs] I don’t know why it is. I think there were a couple basic principles and virtues I have adhered to. You’ve got to be ethically honest. I think it’s very important. You have to be not just honest to science, but honest in business practice and honest to your board. There are some things you just don’t do, don’t even think about. You have to cultivate a certain culture in the company, then everybody follows the same culture. These virtues I learned at Harvard, and MIT Lincoln Lab taught me very well too: there are certain things you just never even think about. And then you treat everybody on merits. If you’re good and you surround yourself with very, very smart people, and place them in the right place. If they fail, most likely it’s because you did not do a good job, by putting them in the right places. It’s not because the person has failed. It’s actually the manager failed. He did not put the person in the right place, with the right talent.

Zierler:

Right.

Fan:

And that is very hard for people to understand, and that’s why our employees at Kopin are very loyal. Even at Lincoln Lab my folks were loyal too. A very good example, the Lincoln people who I picked at to join Kopin — the venture capitalists are very smart. They actually made me send them the list of folks I would like to take with me before I had even resigned. When I resigned these people in the list also resigned and joined Kopin. The VCs were shocked that everyone in the list left with me from MIT. They said: there’s no such prior case. Most people won’t want to leave MIT at the last minute, but they all followed you out of MIT. So, they were impressed. They said: you must have something that those people will follow. And some of the people who followed are still in Kopin right now.

Zierler:

So John, what is that something? What do you think it is?

Fan:

I think it’s one word, trust. First, of course, they know I’m ethical, very fair. I watch out for them. And second, I think I’m — maybe I’m putting words in their mouths — is no matter what happens, I will find a way out. And in business, you always have cycles. Whatever you do, when the cycle is off, business is going to decline, and either you sell it or do something different. And that’s why most companies, technology companies in particular, cannot last for a long time, because whatever is popular and widely adopted, a few years later, the technology and product would shift and the downward wave comes in. You are swept away. Right? So, therefore the company must transform into something different, and quickly. Our folks are confident that we would find new concepts and find new ways out.

Zierler:

John, it sounds like baked right into the origins of Kopin are that flexibility, that recognition that technologies change, consumer interests change, and that for Kopin to survive long-term, it needs to be flexible accordingly.

Fan:

Yeah. So, one thing you learn is to adopt as much as possible the practice of early days of Bell Lab and Lincoln Lab – to keep your R&D funding flexible.

Zierler:

Yeah.

Fan:

So you can do a switch or pivot. Right? Here, especially in technology now, a switch now requires a lot more resources, money and dedicated efforts. You have to convince a whole bunch of people: convince yourself, your people around you, and then you have to convince your board, and you have to convince your shareholders, or convince the government funding agencies. It’s not as easy as it used to be in the Bell Lab days. So, what we did is: by raising enough money, be an incredible fundraiser, so the shareholders will keep on feeding you until you’ve gotten over the hump. Or you get rid of some business — sell some business, get some cash, and you invest it in a new one. In our case, the wearables has been delayed for years, we sold our successful cell phone business and poured our resources into the wearables business. We rode to great success two decades ago, riding the Internet and smart phone wave. Now, we expect a new wave of 5G and wearables.

Zierler:

John, given what a risky venture technology is generally — venture capital and technology — at what point over the past 30, 35 years did you start to feel that Kopin was viable for the long term, that it would not be like so many of those other fly-by-night companies that came and went, and you never heard from them again? Was that a gradual realization for you, or did you wake up one day and realize, “I have something that’s solid. It’s going to be here for the long term”?

Fan: