SOFIA with its telescope door open during a test flight over the Sierra Nevada mountains.

Jim Ross / NASA.

The history of science holds many tales of heroic perseverance, with scientists and their backers vindicated after serial setbacks and years of hard, frustrating work.

The James Webb Space Telescope is one such story. Advocacy for the project began in the late 1980s, and development ramped up in the 2000s. Then, the telescope became mired in problems and was threatened with cancellation in 2010, but work continued, and it launched in 2021. Now, the telescope is returning a constant stream of groundbreaking observations and should continue doing so for many years, and concerns about its extraordinary $10 billion price tag are seldom expressed.

The airborne Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy, or SOFIA, has a similarly eventful history that unfolded in parallel with the Webb telescope’s. SOFIA, though, has become irrevocably associated with a difficult policy question: When is it time to give up and cut your losses—even when they are weighed against substantial gains?

SOFIA received the endorsement of the 1991 iteration

SOFIA’s original justification

NASA’s History Office recently released a report on SOFIA

When the concept for SOFIA was first broached in the run-up to the 1991 survey, the idea of building an airborne infrared telescope made good sense for a number of reasons.

Foremost, ground-based telescopes have difficulty capturing infrared wavelengths due to atmospheric moisture, meaning it is beneficial to observe from a platform either in space or high in the atmosphere. A smaller airborne infrared telescope, the Kuiper Astronomical Observatory, had been operating since 1974 and was considered quite successful. By the late 1980s, it had discovered the rings around Uranus, detected an atmosphere around Pluto, and analyzed the chemical composition of Halley’s comet, among other accomplishments.

Meanwhile, the era of large space telescopes was just beginning, with the Hubble Space Telescope launching in April 1990. To take advantage of the promise of space-based platforms, the decadal survey also recommended a project called the Space Infrared Telescope Facility, which was renamed the Spitzer Space Telescope and launched in 2003. In the early 1990s, it was expected that SOFIA, the space-based telescope, and a proposed ground-based infrared-optimized observatory in Hawaii would together lead the way in an upcoming “decade of infrared astronomy.”

Rosson points out that infrared astronomy was seen as a hot topic at that moment, worthy of multiple major projects, largely because enabling technologies developed for missile-detection systems were being declassified. These included solid-state detectors sensitive to infrared wavelengths and in-space cryogenics needed to cool the space-based telescope so it would not emit interfering heat radiation. Having an airborne telescope was regarded as useful principally because it could be upgraded over time, making it a testbed for new generations of equipment and enabling operations long after its space-based cousin had exhausted its cryogen.

A troubled development

A chart showing SOFIA’s development timeline presented in an audit of the mission’s management conducted by NASA’s Office of Inspector General in 2020.

NASA OIG.

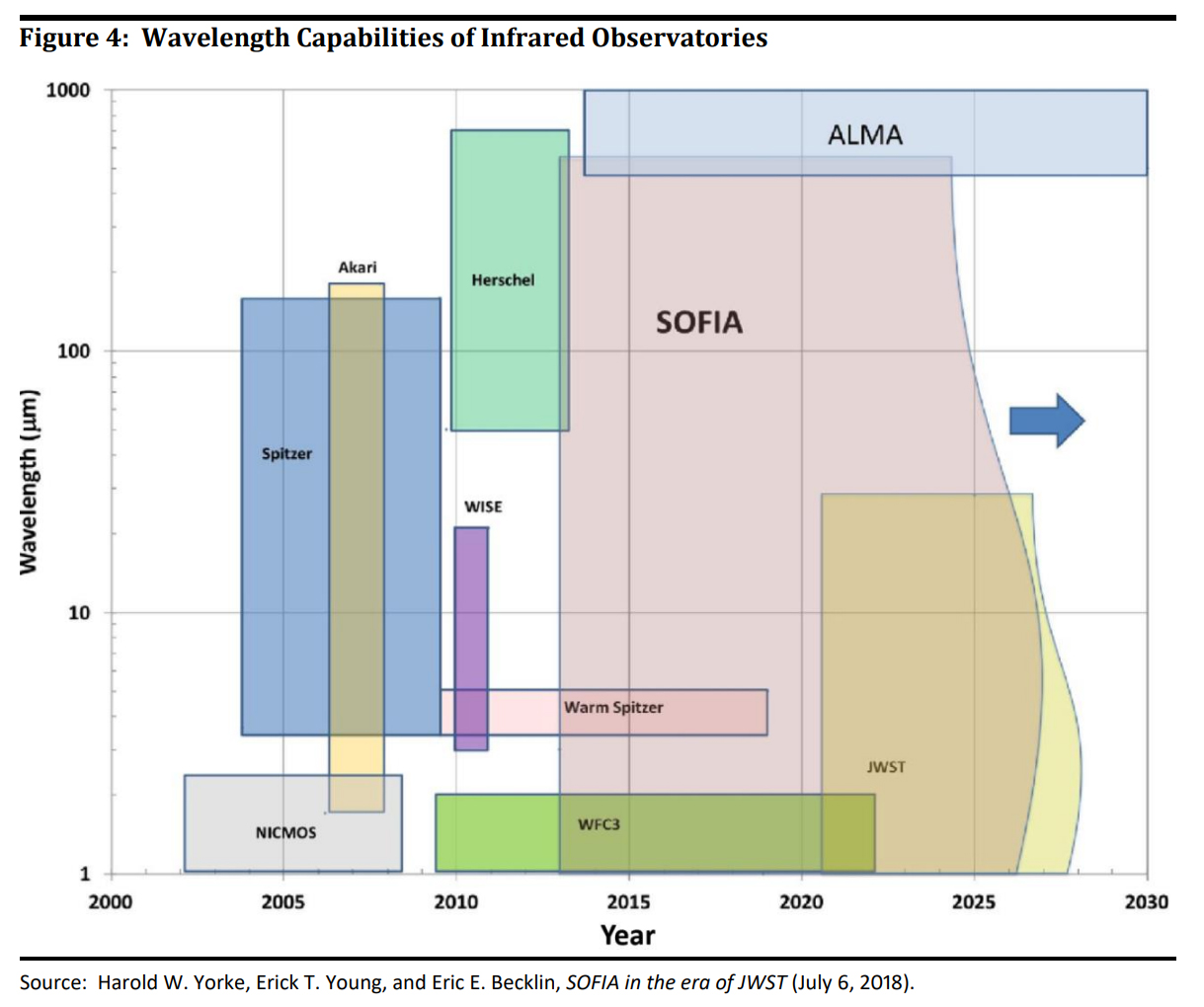

From initial proposal to launch, cost estimates for SOFIA’s development climbed from $230 million to over $1 billion, and its annual operating costs were around $85 million. Perhaps more importantly, the project was repeatedly delayed, with work starting in earnest in the mid-1990s and its completion pushed back by over a decade. Thus, as the financial burden of the telescope increased, its ability to deliver pathbreaking observations decreased as its completion trailed behind other infrared telescopes, including the Spitzer telescope and the European Space Agency’s Herschel Space Observatory. Moreover, although the Webb telescope was likewise delayed, its revolutionary infrared capabilities loomed on the horizon.

A chart created by SOFIA mission leaders showing how its ability to observe in different infrared wavelengths compared over time to other observatories. The chart was also included in an audit of SOFIA’s management that NASA’s Office of Inspector General completed in 2020.

When major science projects run into trouble, there is seldom a single cause, and efforts to weigh competing factors—such as funding availability, project management, and technical decisions—can be complicated and contentious. Notably, Rosson’s study of SOFIA was preceded by another, longer one

In broad strokes: The start of work was delayed several years, partly because NASA’s German partners on the project were contending with budget constraints linked to the country’s reunification. While budget constraints were relieved by the mid-1990s (partly through retirement of the Kuiper telescope), NASA was still eager to find budgetary efficiencies and so assigned the project to a non-government prime contractor, Universities Space Research Association, while Ames retained project oversight.

In addition to splitting responsibility over the project, Rosson notes the management arrangement raised questions around Ames and USRA’s ability to deal with the numerous difficulties involved in converting a 747SP airframe acquired from United Airlines into an astronomical platform. These were exacerbated by United’s 2003 bankruptcy, the loss of maintenance expertise as United took the 747SP out of service, and increased scrutiny of safety prompted by the loss of Space Shuttle Columbia.

With costs and schedule delays mounting, the George W. Bush administration proposed defunding SOFIA in its budget request

Rosson notes that this move was disruptive and controversial and was the target of Kunz’s sharpest criticisms. But, in any event, Congress funded the reogranized SOFIA project, and the telescope achieved its “first light” milestone in 2010. Yet, once the observatory was fully equipped in 2014, NASA quickly moved to terminate it. Congress ultimately protected SOFIA until 2021, when the latest iteration of the decadal survey lent its weight to the decision to end the mission.

Why NASA terminated SOFIA

As SOFIA’s delays and costs grew, at some point NASA officials decided that its expected value for science no longer justified its expense, even if by 2014 termination meant abandoning a new and fully functioning observatory.

Had SOFIA been a spacecraft, its operation might have continued indefinitely since the costs of space missions generally plunge after launch. As a large aircraft, though, SOFIA’s ongoing operating costs were far higher than those of NASA’s space-based telescopes, except for the flagship observatories Hubble and, eventually, Webb. SOFIA’s inherent limitations—not least that it could only observe during flight—meant it had far lower productivity than those missions. If in 1991 there was a strong case to be made for a large airborne telescope, a quarter-century later there was less to recommend it.

While SOFIA unquestionably still had value, NASA, working under finite budgets, had to consider the tradeoffs. Congress, often regarded as a reluctant funder of science, did not feel such constraints. It is common for small groups of lawmakers to champion specific science projects, usually to advance state or local interests, and sometimes in defiance of the White House and even science agencies themselves. Thus, SOFIA’s champions ensured the observatory would leave a scientific legacy, albeit by expending hundreds of millions of dollars that NASA would have preferred to use elsewhere.

It is almost inevitable that decisions to cut losses will be controversial. As Rosson notes, cost growth and delays are not uncommon for large projects, and, as the case of the Webb telescope illustrates, it is often worth it to press through them. Yet, perseverance is not always the best policy. Studying cases like SOFIA’s offers a more nuanced view of the complicated considerations that policymakers can face.

William Thomas

American Institute of Physics

wthomas@aip.org

You can sign up to receive the Weekly Edition and other AIP newsletters by email here.