Rollo’s Experiments frontispiece and title page.

Allison Rein

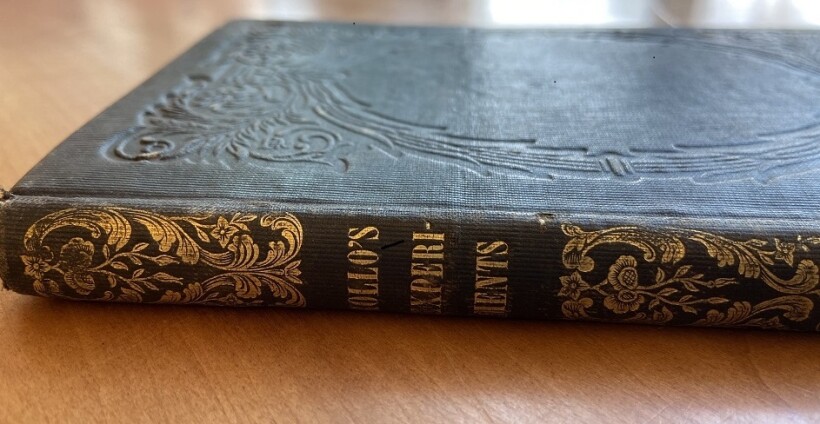

Rollo’s Experiments cover and spine.

Allison Rein

Catalog link

Rollo’s Experiments frontispiece and title page.

Allison Rein

Rollo’s Experiments is a 19th century novel intended to teach about science. It’s one of the earliest examples of the use of juvenile literature, juvenile fiction in fact, being used for scientific popularization and education. The book starts off with Rollo wanting to figure out why the sun shines farther inside the barn in the winter, than in the summer. His friend Jonas says it’s because they want the sunlight more in the winter and Rollo says “I don’t believe the sun moves about in the heavens, to different places, only just to shine into barn doors.” So they decide to do an experiment to track the sun’s light.

The Niels Bohr Library & Archives is particularly interested in physics education, in all its forms, whether it’s more popular works like The Magic School Bus or classic physics textbooks. We collect broadly so we can trace not only how science itself has changed over time, but also how our understanding and learning about science has changed. Science popularizations are fun for librarians to collect because they’re written for us, as we’re not scientists, unless you really consider library science a true “science.” But these books were meant to spark curiosity and engage the reader; they don’t assume a base level of knowledge or use jargon.

The study of science popularizations is also fascinating for historians of science, Joanna Behrman, Assistant Public Historian at AIP says,

Because it offers a window into the value system of science. This can mean both how science “ought” to be done, but also what aspects of nature are worthy of study and who is worthy of studying them. Children’s literature like Rollo’s Experiments, which are not meant only for future scientists but all children whether or not they continue in science, can also offer insight into what value scientific knowledge holds for any individual and thus also for society as a whole. Does someone need to know some level of science to be a good citizen, for instance? Or does knowing the processes of science build intellectual abilities or good character?

These are questions we’re still grappling with today.

Elinor Wonders Why image.

IMDb

What’s especially fascinating about this book, is that even though it was published over 150 years ago, it bears a striking resemblance to STEAM edutainment for children today. The children’s tv show Elinor Wonders Why

The Rollo Series, by Jacob Abbott, which Rollo’s Experiments is a part of, also has an interesting publishing history. The publisher hired Abbott to write a text to accompany illustrations. Jacob Abbott himself was a minister, though he studied natural philosophy and mathematics at Amherst College, and he wrote the Rollo series not so much to entertain as he did to teach morality to his young readers. Other books in the series feature Rollo at work, play, school, vacation, a museum, traveling, corresponding, and reckoning with philosophy. The books are clearly intended for a young audience, as they were written in very simple, plain language. In fact, Abbott wrote some of the first true fiction series specifically for children in the country.

Below are some other children’s and educational science books from the 19th and early 20th centuries, followed by more modern books.

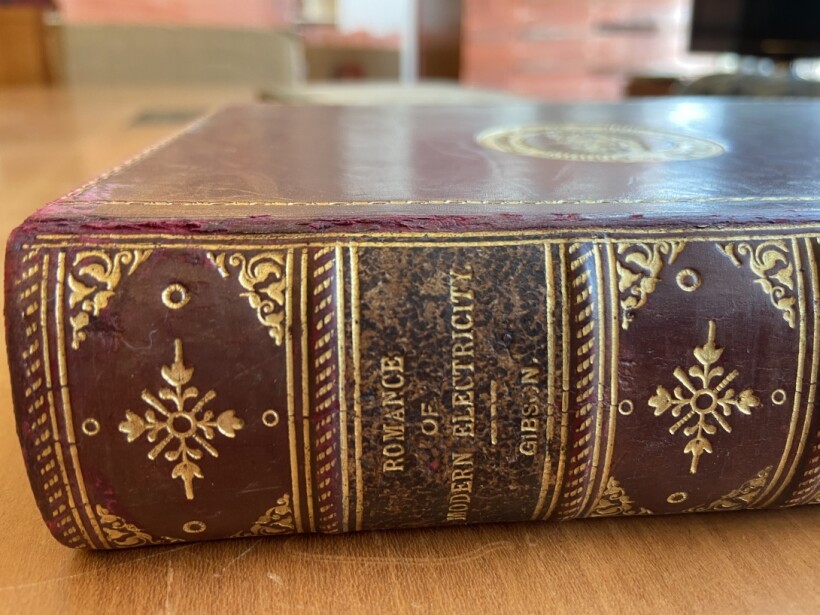

Spine of Romance of Modern Electricity

Romance of Modern Electricity by Charles Gibson, 1908

Catalog link

Not only are school children the intended audience for this book, it was also bound and given out as a school prize by the Market Harborough Country Grammar School. This copy of the book was presented by Fellows of the Royal Institute of British Architects to Alfred Neal Jesson as an award for his drawing skills in 1909. Alfred perhaps didn’t treasure the book that much (I can’t blame him, if I’d won a prize for my art I don’t think I’d want a book on electricity, maybe some nice colored pencils?) because there’s also a book plate from Peter Beaumont Flegg. Check out the image gallery at the bottom of this post to see the prize plate and other fun bits of this book.

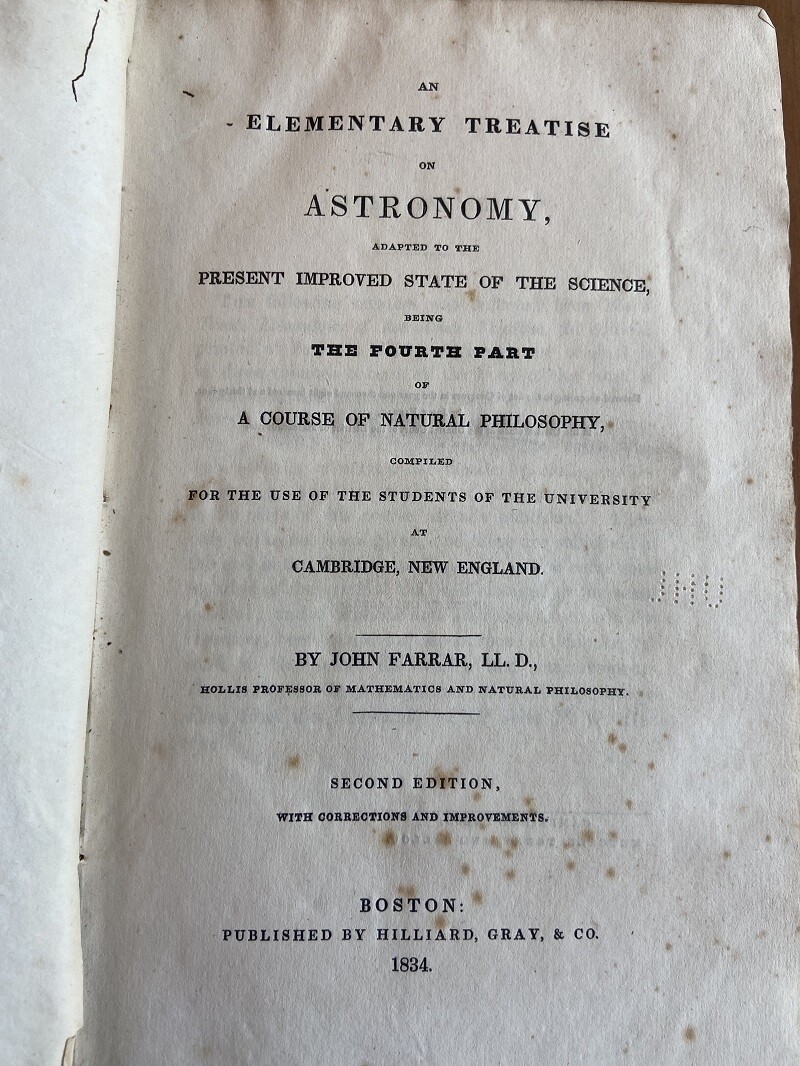

Title page of Elementary Treatise

Elementary Treatise on Astronomy by John Farrar, 1834

Catalog link

John Farrar clearly intended this book for use by students as he published this course on natural philosophy he taught at the University of Cambridge (not the one you’re thinking of, this is just a fancy way of referring to Harvard, which is famously not fancy enough). John Farrar was a professor at Harvard and introduced modern mathematics to the curriculum. He was also an early storm-chaser of sorts; he published his observations of the Great September Gale of 1815

Elements of Descriptive Astronomy

Elements of Descriptive Astronomy by Herbert A. Howe, 1898

Herbert Howe was a Professor of Astronomy at the University of Denver and Director of the Chamberlin Observatory and he wrote this book for both beginners and more advanced scholars in mind. He was passionate about students doing astronomical observations with their own eyes, “though they may be bewildered by such work at first, they will soon learn to delight in it” (Howe IV). He encourages students to keep a record of their observations of the night sky with sketches and other results.

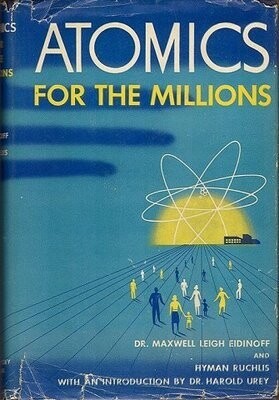

Cover for Atomics for the Millions

Atomics for the millions / by Maxwell Leigh Eidinoff and Hyman Ruchlis, illustrated by Maurice Sendak, with an introduction by Harold C. Urey, 1947

Catalog link

Atomics for the Millions is our modern books star acquisition for 2021. Published in 1947, it is significant for its content and context, but perhaps more so for its engaging and fantastic illustrations. You might recognize the name of the illustrator, Maurice Sendak, for a mildly popular* children’s book: Where the Wild Things Are (1963).

Chapter heading illustration for “Atomic Secrets from Empty Tubes” in Atomics for the Millions. Illustration by Maurice Sendak.

In 1947, the field of physics was changed forever by the development of the atomic bomb and its role in World War II. Physicists were lauded for its creation, but the public was also in need of explanations of this new technology. This book was written with non-technical language and furnished with cartoon-style illustrations with the intention of explaining atomic technology to school-aged children and to adults, making “atomics” accessible for everyone. The co-author, Hyman Ruchlis, happened to teach high school physics. Maurice Sendak was an eighteen-year-old student in his class and was known for his illustration work in the school’s literary magazine. Ruchlis asked Sendak to do the illustrations for Atomics for the Millions, giving Sendak his first book illustration job. NBLA’s copy of the book has the dust jacket, which is somewhat rare.

*By which we mean enormously, wildly popular.

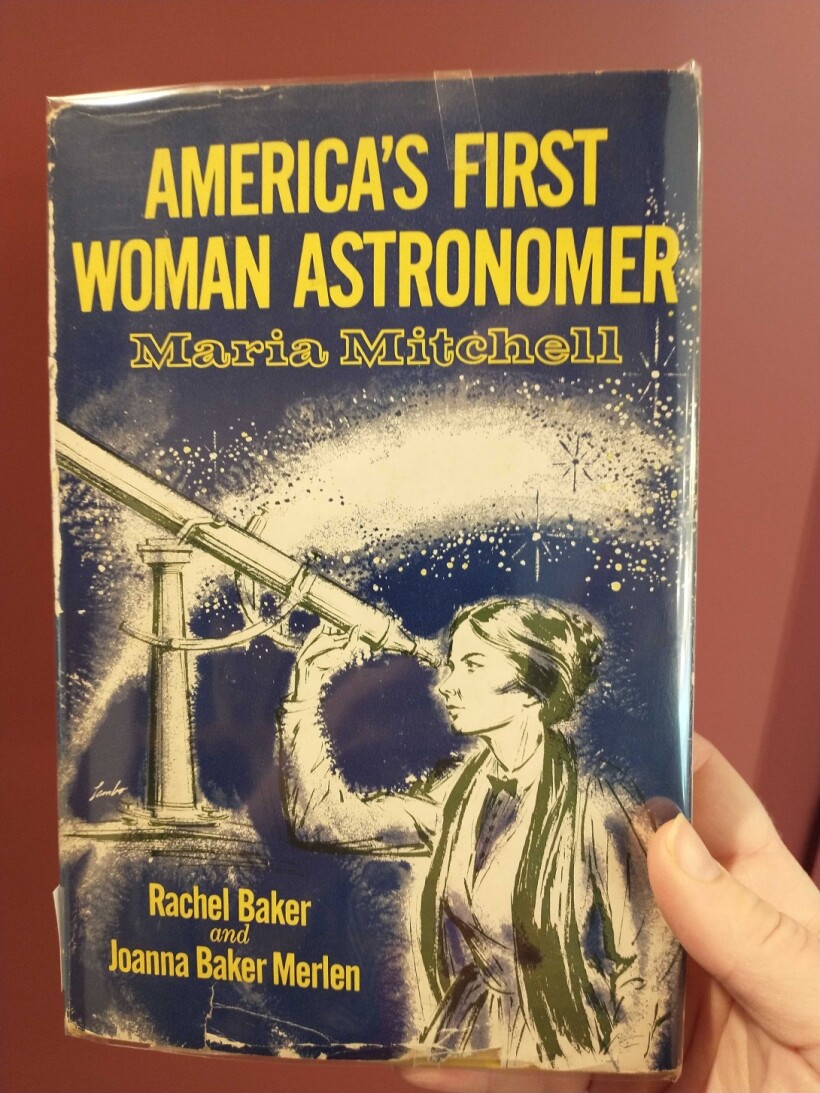

Cover of America’s First Woman Astronomer: Maria Mitchell

America’s First Woman Astronomer: Maria Mitchell by Rachel Baker and Joanna Baker Merlen

Catalog link

A better title for this book would be America’s First Recognized Woman Astronomer, as there were astronomers before Maria Mitchell, but she was significantly the first woman Professor of Astronomy at Vassar College and the first woman elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. This delightful fictionalized biography, published in 1960 and written by a mother-daughter team, is written in accessible language for a younger audience, intended to inspire girls and young women in the time it was written. Though Maria Mitchell isn’t perhaps a household name, this is one of the earlier examples of a book that is only about Mitchell and that popularizes her life and accomplishments. It’s one of several books that we purchased with inspiration from Margaret Landis’ 2021 Honey and Beeswax prizewinning bibliography

Cover of Nikola Tesla for Kids

Nikola Tesla for Kids: His Life, Ideas, and Inventions, with 21 Activities by Amy O’Quinn, 2019

Catalog link

What could make historical figures more interesting, even such a fascinating figure as inventor and physicist Nikola Tesla? Activities! Specifically, scientific experiments. In addition to constructing electric circuits and investigating the nature of electromagnetic waves, activities include making fluorescent slime.

Cover of Marie Curie for Kids

Marie Curie for Kids: Her Life and Scientific Discoveries, with 21 Activities and Experiments by Amy O’Quinn, 2016

Catalog link

Similarly, Marie Curie for Kids draws the reader into Marie Curie’s world with a powerful combination of stories about Marie Curie’s work and personal life, her science, and integrated activities: including examining real World War I X-rays, making a model of the element carbon, and making traditional Polish pierogies.

Cover of The Science of Rick and Morty

The Science of Rick and Morty by Matt Brady, 2019

Catalog link

Love it or hate it, the TV show Rick and Morty, starring mad scientist Rick and his grandson Morty, is undeniably a modern cultural phenomenon. How do the wacky intergalactic adventures in the show relate to real-life biology, physics, and chemistry? This book gives readers a way to understand concepts like dark matter and human regeneration in a different way. Readers can also consider how science is portrayed in pop culture in the late 2010s. An unconventional education indeed.

Cover of Quantoons

Quantoons : metaphysical illustrations by Tomas Bunk, physical explanations by Arthur Eisenkraft and Larry D. Kirkpatrick 2006

Catalog link

NBLA has many graphic novels and books with illustrations, but Quantoons has perhaps the most detailed comic-style illustrations in the collection. From the publisher: “Quantoons combines challenging problems and provocative quotes with intricate drawings that mix Isaac Newton and Marie Antoinette with Romeo, Juliet, and Einstein. The book is a compilation of 58 contest problems that ran between 1991 and 2001 in Quantum magazine; a collaboration between U.S. and Russian scientists that was published by the National Science Teaching Association. In addition to serving as a reader- involvement device, the problems and cartoons were intended to make inquiring minds think about physics and art in new ways and have fun doing it. When you open Quantoons, you‘ll be instantly attracted to the colorful cartoons, densely populated with quirky characters that look like something out of MAD magazine. And no wonder: Illustrator Tomas Bunk is a regular contributor to that publication! But when you pull yourself away from the drawings, you’ll find that they work with the text to give new context to interesting physics concepts. For example, a Quantoon that explores the classic physics problem of crossing a raging river and determining where you‘ll land on the opposite shore is accompanied by a funny/sad metaphorical cartoon about traversing the river of life from birth to death.”

Cover of What Miss Mitchell Saw

What Miss Mitchell Saw, written by Hayley Barrett, illustrated by Diana Sudyka, 2019

Catalog link

This beautiful picture book is a biography of Maria Mitchell (pronounced Ma-Rye-Uh, the book adamantly states on the first page), astronomer, librarian, teacher, and discoverer of the eponymous Miss Mitchell’s Comet (official astronomical name C/1847 T1). Grown-ups and kids alike will enjoy this one because it’s a joy to read and to view. Instead of covering Miss Mitchell’s life in excruciating detail, the author focuses on a couple of themes throughout Maria Mitchell’s life: naming and seeing. Through this repetition of Maria seeing and naming stars, ships, shopkeepers, etc. we know that it was significant that she saw a comet and even more astounding that she got credit for her work. The book ends with the powerful line, “Miss Mitchell saw a comet. The world saw her.”

Cover of The Flying Circus of Physics

The Flying Circus of Physics, 2nd ed., by Jearl Walker, 2007

Catalog link

In 1968, Jearl Walker had an eye-opening moment: after failing a physics test, a student asked him what any of it had to do with real life. Walker was stumped in the moment and failed to come up with an example. He then embarked on a journey to find hundreds of real-life examples of physics for students, and the first edition of The Flying Circus of Physics was published in 1975. Both editions are written in non-technical, engaging language and have questions and answers, accompanied by illustrations. NBLA has had the first edition for many years and we were happy to add the second edition to our collection last year. In this second edition, published in 2007, Walker presents entirely new questions and answers, such as:

Page from The Flying Circus of Physics, 2nd ed.

Subscribe to Ex Libris Universum

Catch up with the latest from AIP History and the Niels Bohr Library & Archives.

One email per month