Cover of The Uranium Club. Credit: Jacket design by Jonathan Hahn, front cover photo and contributor photo: John T. Consoli/University of Maryland

Miriam Hiebert wrote The Uranium Club: Unearthing the Lost Relics of the Nazi Nuclear Program

Cover of The Uranium Club. Credit: Jacket design by Jonathan Hahn, front cover photo and contributor photo: John T. Consoli/University of Maryland

Corinne Mona: Tell us a bit about the book! And please describe the excitement and mystery of the uranium cube.

Miriam Hiebert: One of the features of the story of the uranium cubes that I like best is that there is really something for everyone. There is history, science, spy craft, intrigue, adventure, and grudges between disgruntled physicists. When I was first handed one of the uranium cubes in Tim’s office in 2016, I knew that there was an incredible story behind its journey from World War II Germany to College Park Maryland, but I didn’t expect the breadth that the story would cover. I really have been on the most marvelous adventure tracking down the history of these objects and hope that that excitement translates through the text.

I understand that you’re a PhD in Materials Science. What is your background, and how did you find your way to the history of science?

My academic background is in science, but I have always been most interested in the ways in which science and history intersect. My Ph.D. research, and my current day job, focus on the ways in which science can be used to increase our understanding of history through the scientific analysis of historic objects. It wasn’t until I met Tim Koeth in my second year of graduate school and was first introduced to the story of the uranium cubes that I began to turn my focus towards the other half of this equation – the ways in which history has shaped and driven science forward.

Why did you start doing research at NBLA?

I was lucky enough to be based out of College Park for the majority of this project, which made it incredibly easy to head down the street to the NBLA. Tim likes to say that most of the research for this book could have been done with just a bicycle! The NBLA is also the repository of a huge amount of documentation from the life and career of Samuel Goudsmit, who is one of the main “characters” in this story and was quite a loquacious individual who wrote and talked a great deal about his experience as a member of the Alsos Mission in the years following the war. The Goudsmit collection was one of my primary resources in piecing this story together.

At the yearly Michigan Symposium in Theoretical Physics, summer 1939. Left to right: Samuel Goudsmit, Clarence Yoakum (Dean, University of Michigan Graduate School), Werner Heisenberg, Enrico Fermi, Edward Kraus, in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Catalog ID: Goudsmit Samuel D24, Credit: AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Crane-Randall Collection

What did you find at NBLA that was useful for the book or otherwise?

The Samuel Goudsmit Collection

Left to right: Otto Hahn, Werner Heisenberg, Lise Meitner, and Max Born at the Lindau Conference of Nobel Laureates in 1962. Catalog ID: Hahn Otto D3, Credit: AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives

Which other institutions did you visit in person or online, and what did you find there that contributed to your research?

Beyond the NBLA, the National Archives, also located in College Park was another resource I relied on heavily in my research. They maintain a large amount of documentation from the Alsos Mission, and this was also where we located the files that pertain to the black-market uranium that was being passed around Europe in the years after the war.

I was also fortunate to able to travel to a few different locations for this project, including the Atomkeller Museum which now stands in the cave in southern Germany where the final nuclear reactor experiment was conducted, as well as the Mineral Museum at the University of Bonn, which is the home of one of the black-market cubes. Additionally, the Hoover Institution Library and Archive at Stanford University was an invaluable resource for piecing together information on the enigmatic leader of the Alsos Mission, Boris Pash, and the Beverly Historical Society in Massachusetts provided some important clues surrounding the cubes’ ultimate fate.

Building at Gottow (Kummersdorf, near Berlin) where Dr. Kurt Diebner’s [nuclear fission] research team built G-I pile, using cubes of uranium oxide and paraffin wax; and G-III, using cubes of uranium suspended in heavy water. Catalog ID: Goudsmit Samuel H21, Credit: Photograph by Samuel Goudsmit, courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Goudsmit Collection

Did you encounter frustrations on the journey of cube discovery, or of researching for the book? Please describe if so.

So much of the research for this project was conducted during the height of the pandemic. While there are fortunately many well digitized collections at the NBLA and other archives which enabled me to continue my work remotely, not being able to travel to these resources in person certainly made the work more difficult.

Beyond the logistical impediments, the research itself had its own frustrations. Archival research relies on there having been a person at some point in the past who, upon looking at a document, decided that the information it contained was important enough to warrant its preservation. What is interesting or important to me today, may not have been so obviously significant to someone several decades ago. This is particularly true for objects like the cubes, which, while totally fascinating today, were really just odd desk trinkets in the years after the war, or even just a little additional uranium that was added to the mass amounts being consumed by the American nuclear program. As a result, hard documentation of the cubes after their discovery by the Alsos Mission was hard to find, and piecing together what happened to them was difficult.

Was there anything in your research journey that particularly surprised you?

The most interesting part of the research for me was the ways in which archival research differs from scientific research. In science research, you set up an experiment in which you have (ideally) controlled for all possible variables and look to see if the result either agrees with or does not agree with the hypothesis you set out to investigate. In other words, you know, before you begin, what it is you are looking for. With archival research, you may set out with a specific question you are hoping to answer, but there is no way of knowing what you are going to find when you open each new box. There is no way to predict that you are going to find the documentation you need, or that that documentation even exists. There is also no way to know what unexpected information you are going to find, or what details, which seemed irrelevant at first, gain meaning and relevance as your understanding expands.

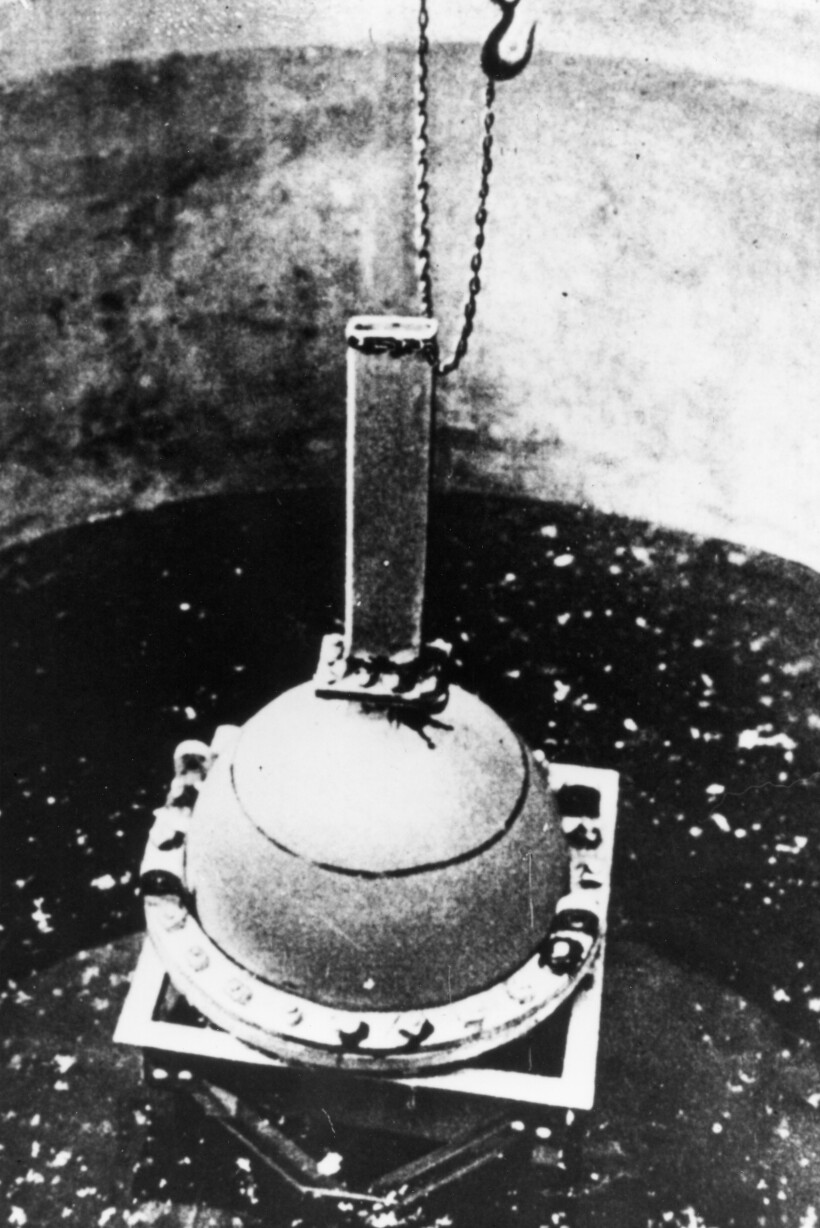

German Pile Sphere. Catalog ID: Alsos H2, Credit: AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Goudsmit Collection

Why is it important to consider Germany’s nuclear reactor attempts?

So much about this history is directly relevant to understanding how we have to collectively approach the large scientific challenges facing the world today. There are a number of reasons underlying the failure of the German program to construct a functioning nuclear reactor in the same timeframe in which the United States undertook the whole of the Manhattan Project. Most are directly tied to the ways in which the German nuclear program was organized and run. Mired in the prejudice that had infiltrated nearly every aspect of German life, and left without a sizable portion of the scientific community who had been forced to flee, the nuclear scientists chose to approach the problem of harnessing fission as an academic endeavor in which they felt they had to compete to maintain control, rather than collaborate in order to succeed. The success of the Manhattan Project stands in stark contrast to the German program in these respects. In a radio broadcast in August of 1945, Eleanor Roosevelt described the work of the Manhattan Project as “the pooling of many minds, belonging to different races and different religions. The way the work was done sets the pattern for the way in which, in the future, we may be able to work out our difficulties, not by setting us superior races, but by learning to cooperate and using the best that each one has to contribute to solve the problems of this new age.” I couldn’t put it any better myself.

What are you doing now? Any future projects we should look for?

Yes! One of the things that bugged me the most as I was working on this book was how few women I got to research and write about. Women have been involved in physics for centuries, but they are still so seldom talked about or given the credit they deserve. I have started working on a project with my friend and colleague Kathryn Sturge (a Ph.D. student in Physics at the University of Maryland) to detail the challenge women have faced in physics throughout history and investigate how these trends continue to impact their participation in physics today.

Is there anything else you’d like to tell us about the book or anything else?

Just to say that none of this work would have been possible without the support and guidance of a huge network of scientists, historians and nuclear enthusiasts to whom I am immensely grateful.

Miriam Hiebert. Credit: Timothy Koeth

Miriam E. Hiebert, PhD, was born in St. Louis, Missouri. She moved east for college, getting a B.S. in Chemistry at the University of Richmond in Virginia. She went on to pursue a doctorate in Materials Science and Engineering at the University of Maryland, and it was during this time that she was first introduced to nuclear history, Tim Koeth, and the uranium cubes. She currently works as a conservation scientist in the DC area.

Koeth, Timothy and Miriam Hiebert. “Tracking the journey of a uranium cube.” Physics Today 72, no. 5.(May 2019): 36–43. https://doi.org/10.1063/PT.3.4202

Mona, Corinne and Karina Cooper. “Radiation Facility Tour.” Ex Libris Universum. 19 December 2023. /history-programs/niels-bohr-library/ex-libris-universum/radiation-facility-tour

Subscribe to Ex Libris Universum

Catch up with the latest from AIP History and the Niels Bohr Library & Archives.

One email per month