100 Years of Physics and Television

John Logie Baird circa 1925 in an early test of televising two ventriloquist dolls using his transmitting apparatus from the 1927 book Television for the Home. (see this blog

Niels Bohr Library & Archives

One hundred years ago today, on January 26, 1926, Scottish inventor and engineer John Logie Baird conducted the world’s first public demonstration

The term “television

In the 1920s, scientists and inventors across the world were experimenting with transmitting images, resulting in varying approaches to the technology. Early pioneers included Baird

For this edition of Photos of the Month, we are going to look at some of the ways the technology of television has been shaped by and helped shape the fields of physics and astronomy in the last century.

Early Television Models

Physicists were involved with the design of television from the very beginning, utilizing numerous technologies such as cathode ray tubes and fiber optics.

Horton, Mathes, and Stolller with television receivers. 1927

Credit Line: Bell Laboratories / Alcatel-Lucent USA Inc., courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Physics Today Collection. Catalog ID: Horton Joseph F2

In April 1927, Bell Telephone Laboratories demonstrated their mechanical television system to the public for the first time. While not the first in the world, the Bell system was much more sophisticated and had higher resolution than any existing models. It not only transmitted images, but also synchronized them with sound and allowed for two-way communication.

The demonstration featured a live transmission of images accompanied by a speech from then-Secretary of Commerce, Herbert Hoover, from Washington, DC, to the AT&T offices in Whippany, New Jersey and New York, using an enhanced radio line. (See a news reel of it from the Herbert Hoover Preseidential Library & Museum

The research for this system was led by Dr. Herbert E. Ives

This image was originally published in a special issue of the Bell Laboratories Record

Two views of a large metal television receiver tube developed by J.B. Johnson, F. Gray and H.W. Weinhart. September 28, 1935.

Credit Line: Bell Laboratories / Alcatel-Lucent USA Inc., courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Physics Today Collection. Catalog ID: Johnson John Bertrand F1

A major step in the development of electronic television was the introduction of the cathode-ray tube. The first working televisions were mechanical, often using a spinning disk to scan an image onto a light sensor. The cathode ray tube (CRT), by contrast, converted images into electron beams transmitted over wire and reconstituted on a screen elsewhere, allowing for more efficient transmission.

In 1922, John Bertrand Johnson

For more on the physics of cathode ray tubes, check out this digitized 1975 physics workbook

Television picture of R.D. Kell taken by moonlight in April 1944 using an early model of the Image Orthicon.

Credit Line: AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives. Catalog ID: Rose Albert H2

In the late 1930s, the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) began working on a more efficient way of scanning and storing images for television using a low velocity scanning beam. Their Image Orthicon was a composite of earlier methods of image dissectors and soon became one of the most commonly used television cameras in the mid-20th century.

The Image Orthicon was developed by physicists Albert Rose, Paul Weimer, and Harold Law for RCA, and was first used by the U.S. Navy in 1944 before being introduced for civilian use in 1946. The key advancement was its ability to pick up moving television pictures in much lower light levels than the previous technologies (which had sometimes been so bright that the heat of lamps had set things on fire). Its sensitivity was similar to the human eye, which allowed for filming in candlelight and moonlight – as the photo above demonstrates in a test run of the technology for the U.S. Navy in April 1944.

Since the Image Orthicon is extremely light sensitive, bright objects can oversaturate the image, giving them a distinctive dark halo. This halo is visible in early televised rocket launches

Fiber optic television transmittal demonstration, 1966.

Credit Line: Photo by John Lawrence, Standard Telecommunication Laboratories, courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Physics Today Collection. Catalog ID: Fiber Optics F9

By the mid-1960s, color television was on the scene and television programming was constantly expanding, increasing the need for more efficient and lightweight ways of transmitting signals across large distances. The Standard Telecommunication Laboratories in the UK pioneered a technique using fiber optic cables in 1966, seen above, which was capable of transmitting a 960-channel color television picture over several hundred meters on just a single glass fiber optic cable. Standard Telecommunication Laboratories was home to fiber optics development pioneer Charles K. Kao, later nicknamed the “father of fibre optics” when he won the Nobel Prize in Physics. While it would be another 10 years before commercial fiber optic communication systems became commonplace, they were used to broadcast the 1976 Olympics and revolutionized telecommunications. They are still used for high speed bandwith for internet and television.

Television for Scientific Research

In addition to contributing to the development of television, physicists have also used television technology in their own research, from remotely monitoring dangerous areas to providing exposures for faint stellar phenomena.

Safely shielded from radiation, two General Electric engineers in a reactor control room at the Hanford atomic plant examine a television screen’s image during a routine check of reactor equipment located in a highly radioactive area of the plant. ca. 1957.

Credit: Digital Photo Archive, Department of Energy (DOE), courtesy AIP Emilio Segre Visual Archives. Catalog ID: Hanford Site F5

Nuclear reactors can have highly radioactive areas, so keeping an eye on them is critical for safety. Here we see a television monitor being used in the control room at the Hanford atomic plant in Washington State to allow two engineers from General Electric to safely check on reactor equipment. Television monitors were built into the design of Hanford

Dr. N. F. Kuprevich, a pioneer in the use of television techniques for astronomy, stands at the entrance to his remotely operated, all television telescope at Pulkovo.

Credit Line: Kitt Peak National Observatory, courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Physics Today Collection. Catalog ID: Kuprevich N F B1

Television has also had a long history in the field of astronomy. Television technology had the ability to intensify the brightness of faint images, as seen with the Image Orthicon earlier, meaning that it was possible to use it to generate a brighter image over a shorter exposure with less atmospheric distortion. Russian astronomer Dr. N. F. Kuprevich at the Pulkovo Observatory in Leningrad, seen above, pioneered the use of television techniques for ground telescopes. The first television telescope at Pulkovo Observatory was constructed in 1958 using a “Superorthicon” camera tube and successfully captured clear images of celestial objects. The photo above was taken on a press trip to Russia shortly after the launch of Apollo 12 in 1969, where reporters were able to see the TV camera at the observatory track the rocket on its way to the moon.

Kuprevich’s full paper

William Livingston places a Westinghouse image orthicon tube in a camera. Using a high sensitivity tube with a “built-in” memory at the Kitt Peak National Observatory near Tucson, Arizona to help astronomers learn more about distant stars. William Livingston places a Westinghouse image orthicon tube in a camera in the observing room of the world’s largest solar telescope. The tube, similar to the type used in a television camera, is used with the telescope’s spectroscope to photograph weak stellar spectra at night. The orthicon tube translates a light image into a video signal which can be displayed on a monitor and photographed for additional study.

Credit Line: AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives. Catalog ID: Livingston William F1

The development of image intensifiers, or methods for sharpening contrast in faint images and observations in astronomy, was a budding area of research in the early 1960s. In 1961, NASA hosted a symposium on the state of image intensifiers where solar astronomer William Livingston, pictured here using a modified orthicon tube at Kitt Peak National Observatory, presented a paper, “Applications of Image Orthicons in Solar and Stellar Astronomy

The orthicon could repeatedly scan and record spectra using the cathode-ray tube which was then integrated numerically with a digital computer to reduce noise and increase accuracy to a precision of 0.01%. The scan rate was able to improve upon the previous method of oversaturating the emulsion on a photographic plate during an exposure, allowing faint scans like the spectra of sunspots to be visible.

Livingston would later go on to use cameras and television to study natural geostationary satellites.

Abraham Schnapf, Manager of Program Management at RCA TIROS, stands with the weather satellite 15 years later in this series of the meteorological spacecraft.

Credit Line: RCA News and Information, courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Physics Today Collection. Catalog ID: TRIOS F2

Television was also utilized by meteorologists in the early 1960s for weather satellites, which allowed remote sensing from space for the first time. TIROS

TIROS-1 was launched in 1960 and was soon followed by three more satellite missions. Over the next two decades, various new generations of TIROS spacecraft were developed as weather satellites, and inspired others. The last of the satellites based on the TIROS design was launched in 2009 and was decommissioned in 2025 after a battery failure. The observations from these satellites aided in daily weather observations and enabled scientists to monitor large-scale cloud phenomena to complement ground-based observatories.

Abraham Schnaf, the project manager for the TRIOS division at RCA, is pictured here with TRIOS-1 before launch. A test vehicle of the original TIROS-1 satellite

Television for Science Communication

Finally, television has been a medium for science education since its earliest days. Some of the first television programs, educational science lectures and demonstrations, and moon landings broadcast live on television brought science to the home introduced many to the wonders of the physical sciences.

Mr. Levitt (left) and William Swann (right) on television. Circa 1955.

Credit Line: AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Physics Today Collection. Catalog ID: Swann William C9

The early days of science public television often consisted of scientists coming on to shows and talking about science, not too different from college lectures with demonstrations. Here we see a shot from a local television program in the Philadelphia area in 1955 with astronomer and inventor Israel Monroe Levitt (left) and physicist William Swann (right).

I.M. Levitt (1908-2004), Director of the Fels Planetarium at the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, was a prominent local science communicator; he wrote a regular local column in the newspaper, published several popular books on science, and appeared regularly on radio and television. He was a colleague of Roy K. Marshall, the creator of the first televised science classroom show, who wrote an article for Physics Today in 1949 called “Televising Science,” which gives a good introduction to the early days of science television. Levitt is also known for his theories about “Martian Time

William Gray Swann (1885-1962)was an English physicist who, as the first director of the Bartol Research Foundation

While it is unclear exactly what show this image is from, given Swann’s and Levitt’s frequent television appearances, it is possible that this is from Swann’s program Horizons Unlimited in the 1950s.

Don Herbert was Mr. Wizard, a television personality teaching science to children in the 1950’s and 60’s.

Credit Line: AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Physics Today Collection. Catalog ID: Herbert Donald A1

Any discussion of science and television would not be complete without mentioning Don Herbert, aka Mr. Wizard, whose show Watch Mr. Wizard ran for over 15 years. A very popular television personality in the 1950s and 60s, Herbert’s popularity marked a shift in focus from educating not only the general public in science but specifically children.

Herbert inspired many other television science communicators, including Bill Nye, who wrote an obituary for him in the LA Times

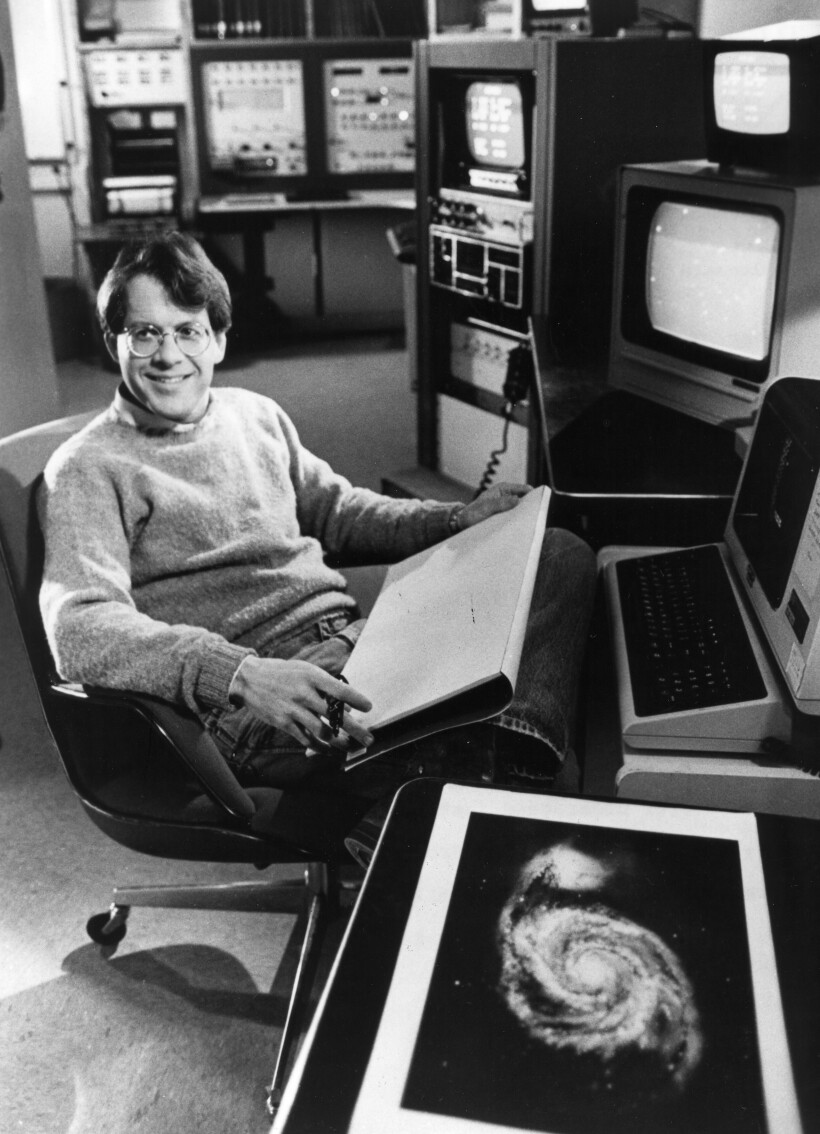

Timothy Ferris, host of “The Creation of the Universe,“a science special which appeared on public television. November 20, 1985

Credit Line: AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Physics Today Collection. Catalog ID: Ferris Timothy F1

While there are many other examples of science communicators on television, to close out this blog post I wanted to feature this photograph of Timothy Ferris, host of a public television special The Creation of the Universe that aired in 1985 on PBS. The establishment of government funding for public television had a massive impact on allowing science educational programming like PBS Nova to reach a wide audience and created some of the best loved science celebrities that have inspired a generation of scientists.

This shot offers a behind-the-scenes look at the planning of a television broadcast. Ferris wrote and presented the documentary, which received great critical acclaim

For more on science communication through television and other media, check out our science communication research guide.

We hope you enjoyed this look back at the last 100 years of television in science. From the early days of physicists developing television technology, to the use of television to perform astronomy, and finally the ways television popularized science to the public, television and physics go hand in hand.