Translating Science History

Dava Sobel

Credit: Glen Allsop for Hodinkee

In 2022, the Niels Bohr Library & Archives became the home of a donation

Dava Sobel is the author of Longitude

Niels Bohr Library & Archives: Please tell us a bit about yourself. How did you become interested in the history of science? What led you to become a writer of popular books on science history?

Dava Sobel: History of Science was an elective course offering at my high school, though I admit I took Analytical Chemistry instead. I came to science writing and history-of-science writing via journalism, getting my first newspaper job in 1970, the year of the first Earth Day. Later I worked as science writer in the Cornell University News Bureau and, in the 1980s, as a science reporter for The New York Times. The Longitude Symposium held at Harvard in 1993 is responsible for transforming me from a full-time freelancer for magazines into an author of books about the history of science.

NBLA: Your books have been translated into many different languages. As part of your donation, we received copies of your books in Korean, Thai, Catalan, and Basque, and many other languages . Can you tell us about what it was like to get translations of your work published from an author’s perspective? Were you surprised to receive these translation requests? Did you have a moment when you realized you had an international reach?

DS: Indeed I’ve been surprised and delighted by the interest from foreign countries. All of those requests and arrangements occurred through my literary agency, now InkWell Management, and ordinarily I had no contact with the foreign publishers or the translators they hired. The shining exception to that rule is Xiao Mingbo, who struck up a conversation by email with me while he was translating Longitude, and who has gone on to translate all my books into Mandarin. At first, each of us a little confused by the other’s name, he thought I was a man, while I thought Mingbo was a woman. Soon I learned Mingbo’s real job was in electrical engineering. He holds a doctoral degree from Purdue University in Indiana. Translating began as a hobby for him, and he is also a serious amateur book collector with thousands of volumes in his home library. In 2008, when I visited Shanghai for a literary festival, we met. The following year, when I returned to Shanghai as part of an eclipse tour, we reunited.

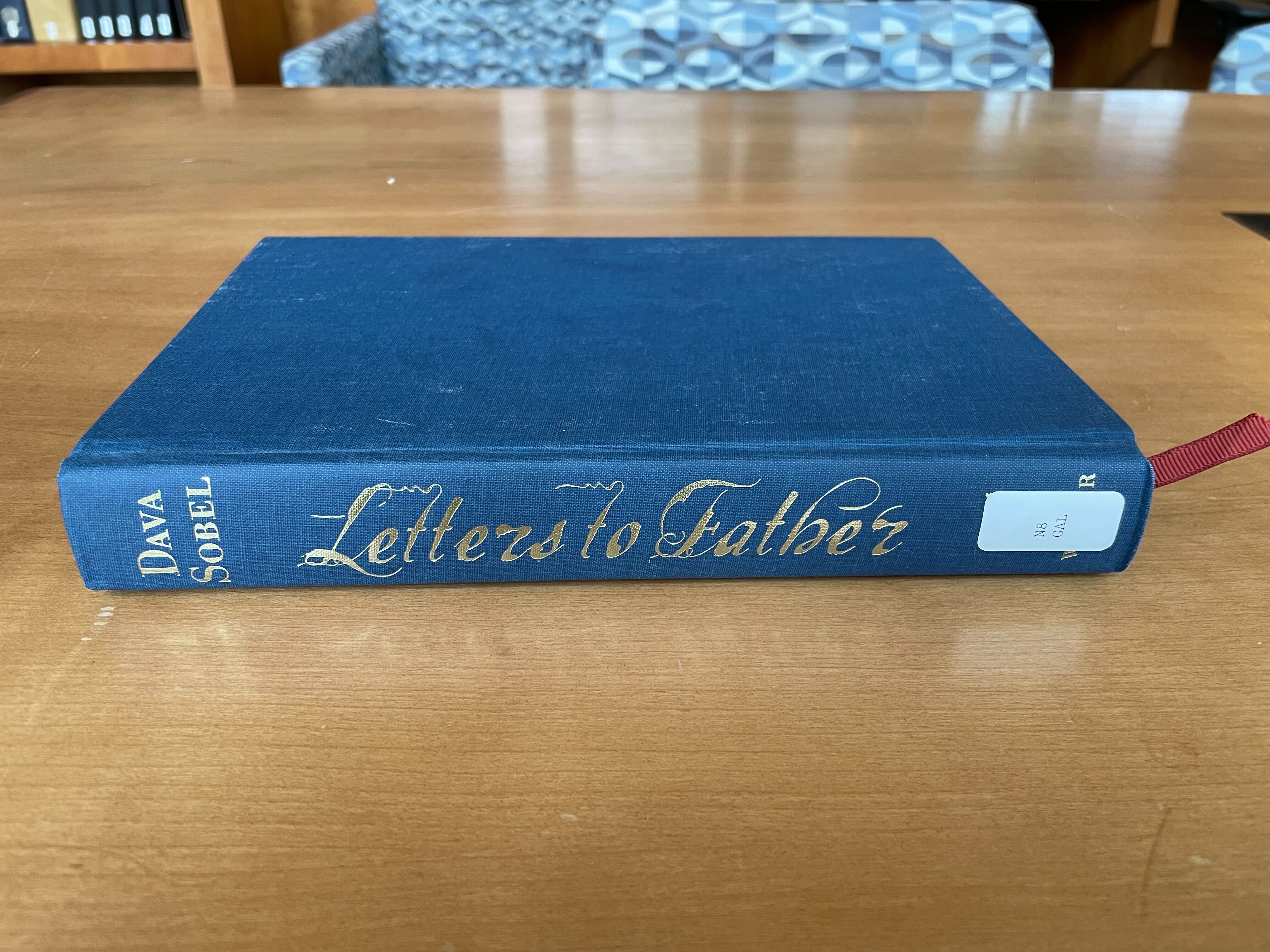

Letters to Father

A peek inside NBLA’s hardback copy of Letters to Father

NBLA: Speaking of translations, your book Galileo’s Daughter and your book Letters to Father

DS: It was my great good fortune — or lucky accident — to have studied Italian in college. I had no compelling reason for taking up another foreign language at the time. Thirty years later, however, when I learned that Galileo had a daughter who was a nun and whose hundred-plus letters he had saved, I already owned the necessary skills (or so I thought) to take on the project of translating those letters and looking at Galileo’s discoveries and trial for heresy through her eyes. Had I needed to turn over the translation work to someone else, I doubt I would have attempted to write that book.

I learned the letters had been published in volume XIII of Galileo’s complete works, and my agent, Michael Carlisle, bought a paperback collection of her letters for me while he was on vacation in Venice. The first thing I did was copy out each letter in my own handwriting. Then I got copies of her handwriting from the library in Florence where the originals are held. Later I spent weeks in that library, handling the sturdy old stationery myself, re-reading with new emotion.

Because my Italian was rusty, I went back to school — an adult-ed conversation class at the local middle school — to hone my grammar. Then I hired the teacher, Mariarosa Gamba Frybergh, as the perfect consultant: She was a retired college professor and a native Milanese with an aunt in a convent. Her home library included the Italian equivalent of the O.E.D., which helped me identify words that had fallen out of use over the centuries, such as the names of small game birds once considered edible delicacies.

It took me a year to translate the letters. I was so slow and unsure of myself at the start that I probably looked up every third word. My first draft of what became Galileo’s Daughter included the full text of all 124 letters. Thanks to the wisdom of my editor, George Gibson, the final draft contained only about twenty full texts and excerpts from others. Those excisions prompted me to offer my translations to Albert van Helden at Rice University, who posted them on his Galileo Project website

Letters to Father came about when Michael Carlisle, my agent, reasoned that the people who most wanted to see all the letters in both English and Italian wouldn’t want to read them on a website (this was 1999). By making the book of collected letters a beautiful object — fine paper, cloth covers, a ribbon bookmark — it could be sold for a high price, and all the proceeds donated to the Poor Clare nuns who had helped me understand the nuances of Catholic devotion and convent life. We were able to give them about $25,000.

A nun, traditionally identified as Suor Maria Celeste, daughter of Galileo Galilei.

Credit: The Welcome Collection

NBLA: Works about Galileo form a substantial part of your donation to NBLA, including all volumes of Le opere di Galileo Galilei

DS: Over the five years I spent in research and writing, I amassed an entire wall’s worth of books by and about Galileo, as well as on Catholicism, Italian history, medicines and herbal remedies of the period, convents, etc. Probably the most significant part of the experience was my correspondence with Mother Mary Francis, abbess of the Poor Clare Monastery of Our Lady of Guadalupe

My research was further informed by visiting all the places where Galileo and his daughter had lived, thanks to a travel grant from the Sloan Foundation.

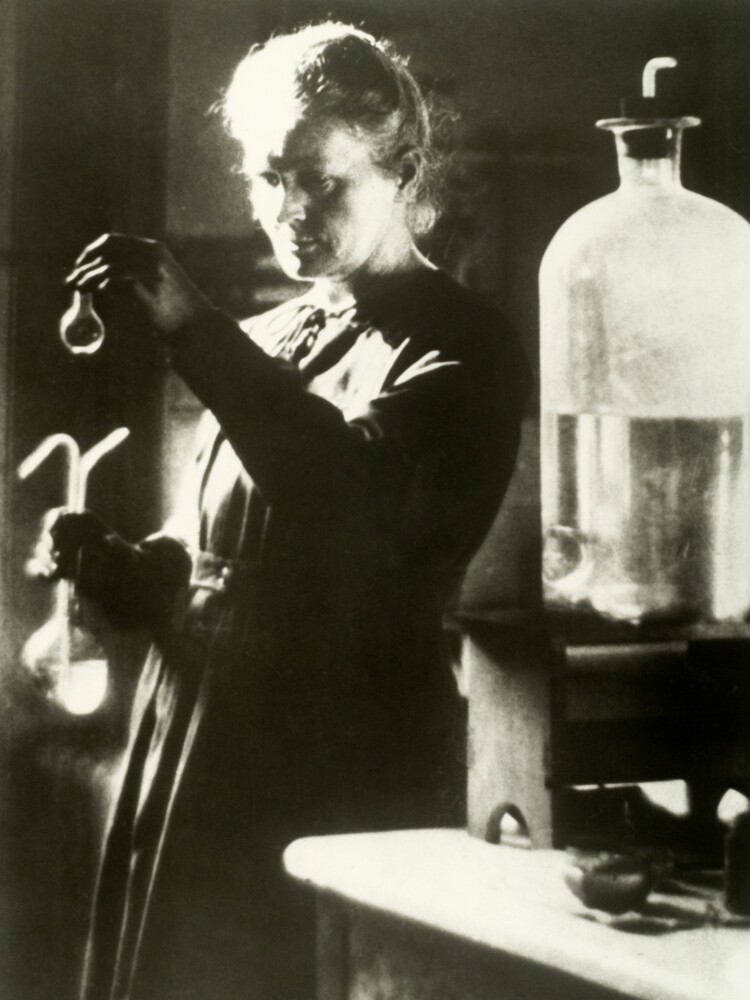

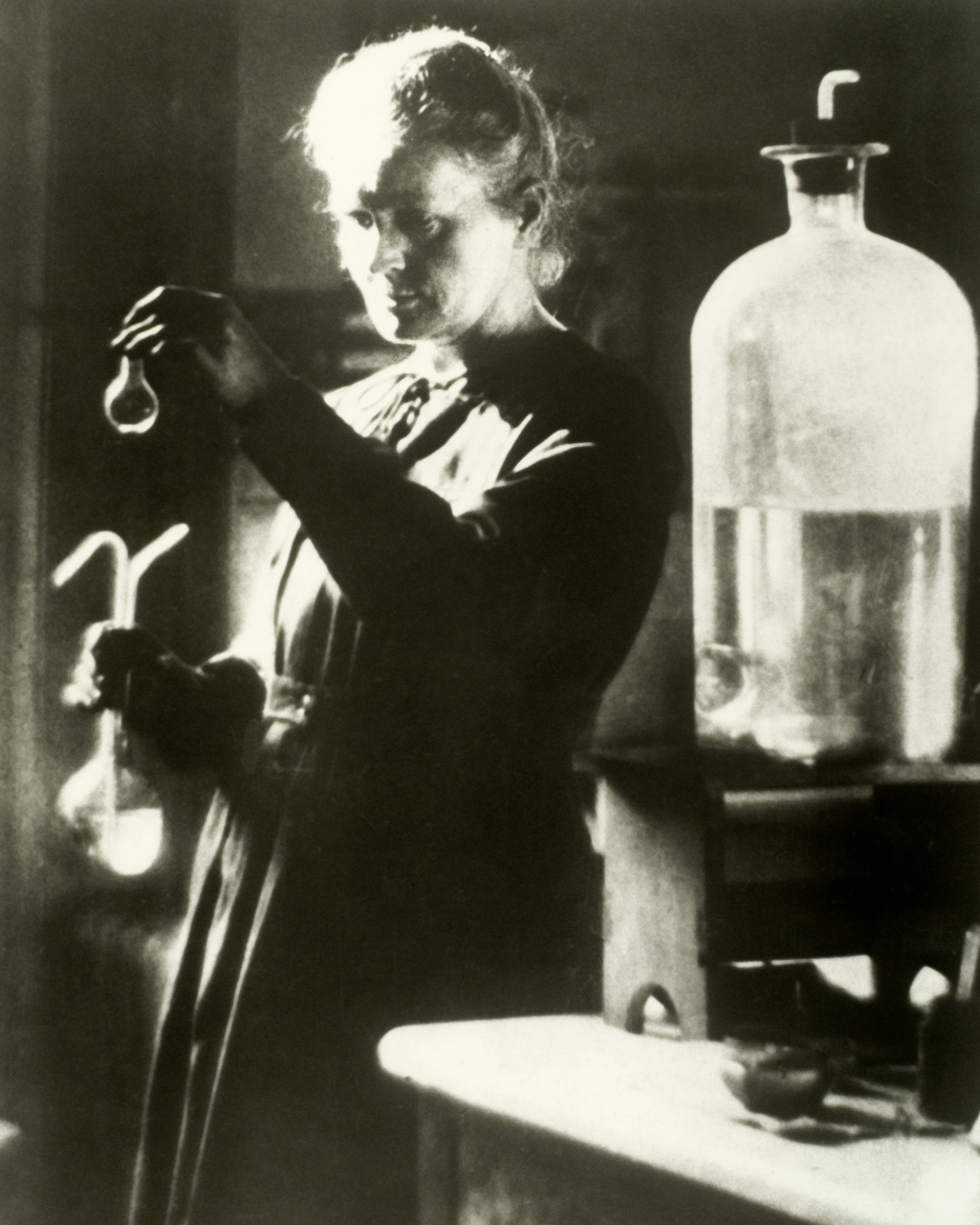

Marie Curie works in her laboratory. Curie Marie B2

Credit Line: Radium Institute, courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives

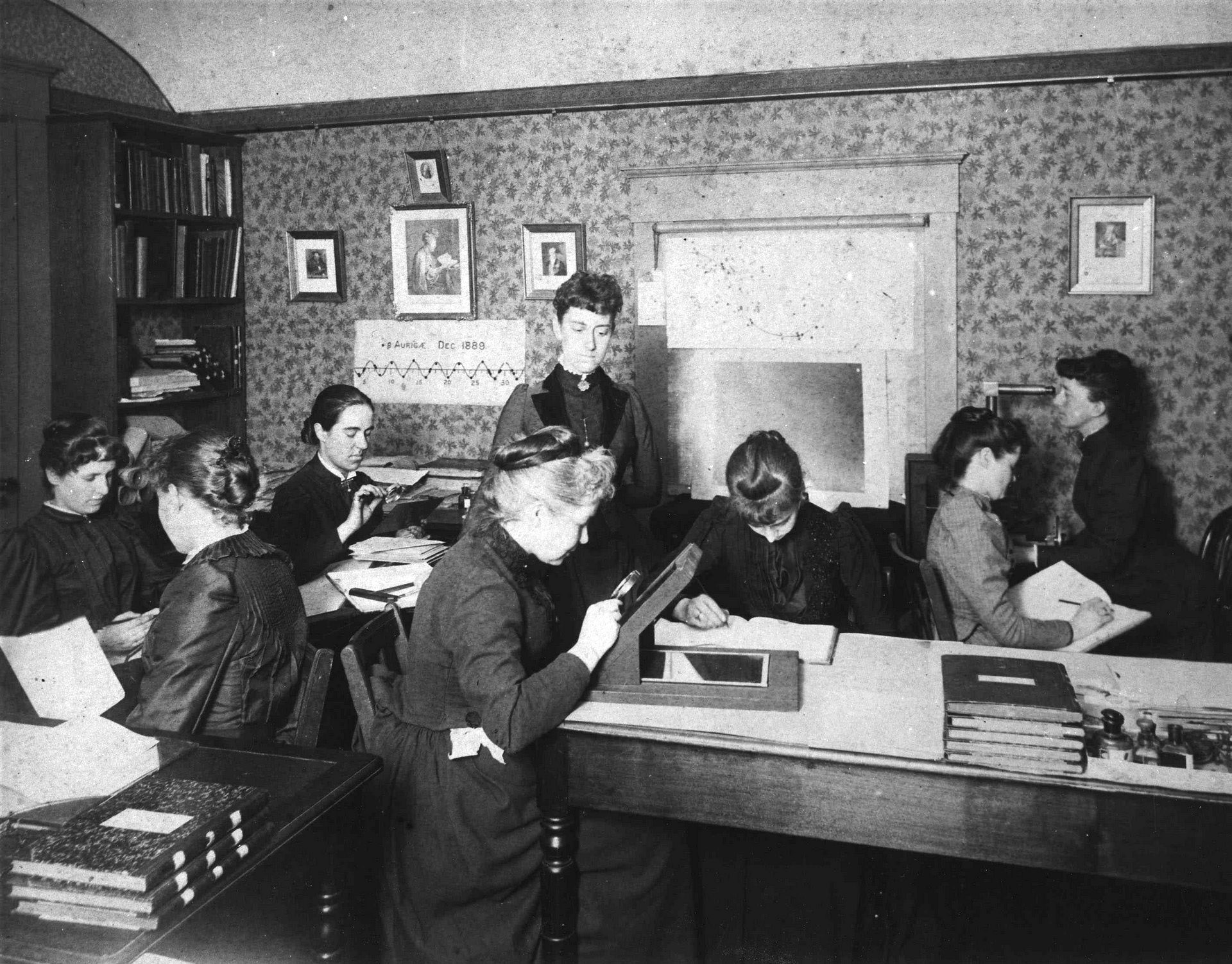

Female ‘computers’ at work at the Harvard College Observatory. Williamina Fleming stands at the center. Harvard College Observatory F1

Credit Line: Harvard College Observatory, courtesy of AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives

NBLA: Many of your books explore the untold sides of scientific figures, especially of women who contributed to science in unique ways– from Suor Maria Celeste, the astronomers of the Harvard College Observatory, and now your newest book on Marie Curie

DS: I am very late in coming to the issue of women in science. For too long, I didn’t even realize it WAS an issue. (I don’t count Suor Maria Celeste as a woman scientist.) Given my personal and professional interest in astronomy, I wanted to tell the story of the female computers at the Harvard College Observatory who wound up making some of the most profound contributions to the understanding of stars — their composition, evolution, and distribution through space — in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As I learned the details of what they had done, however, I found myself constantly surprised by their insights and discoveries. I had to admit I had approached them with embarrassingly low expectations. That’s when I diagnosed what I can only call my own latent misogyny. Soon I realized that some of the women astronomers who were advising me on that project suffered the same unacknowledged prejudices.

That experience made me want to tell other stories about women in science. I shied away from Madame Curie at first, given her great fame, but then, learning how many other women she had welcomed into her laboratory — how many chemists and physicists still credit her with inspiring their careers — I had something new to say about her.

I also wanted to describe the experiments that went on in her laboratory and were the focus of her great intelligence. She, perhaps more than any other historical figure I’ve written about, can help a non-scientist appreciate what a life devoted to science is like.

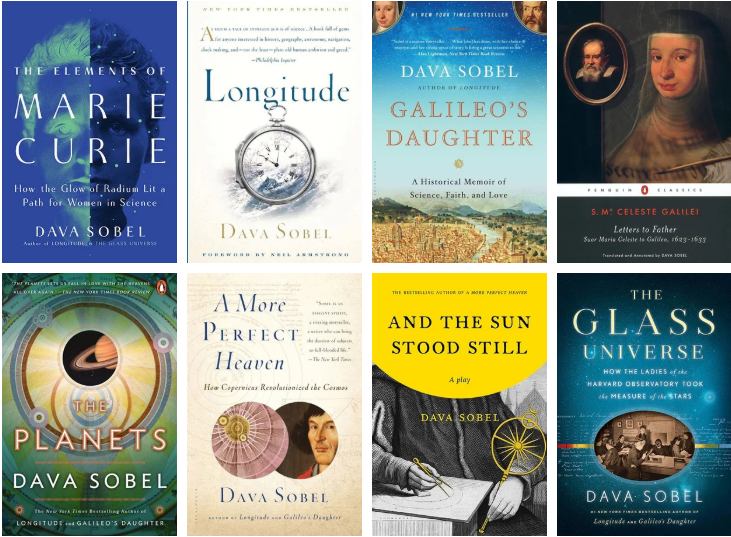

Covers of Dava Sobel’s Books

Credit: https://www.davasobel.com/

NBLA: Your books all have gorgeous covers. Do you have a particular favorite, from your English books or from your books in translation? From an author’s perspective, how involved are you with book cover design?

DS: I am the happy beneficiary of so many beautiful book covers. Most of the American jackets were the work of a single individual, Evan Gaffney, while the latest one (Elements of Marie Curie) was designed by Alex Camlin. I’ve had little or no input over the years, nor would I want any, as I possess zero artistic talent. Only two or three times have I needed to say, “That design just isn’t working for me” or “This design doesn’t seem to represent the book” or words to that effect. And on those occasions the publishers have agreed to try again.

NBLA: Do you have another project in the works?

DS: I’m not writing another book at the moment. I’m still “post-partum” after Madame Curie and busy giving talks about her. I also edit “Meter

Examples of poems on the monthly Meter column in Scientific American