The Faces of Sisters in Science

In June we featured an interview

Hedwig Kohn

Hedwig Kohn with school class in 1906 (Kohn is 3rd girl from left).

AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, gift of Dr. Wilhelm Tappe, Kohn Photo Collection

Kohn Hedwig D9

Hedwig Kohn was born in 1887 to German Jewish parents in Breslau, a city that is now part of Poland, but was then part of the pre-WWI German Empire. Her parents encouraged her to get an education at a time when opportunities for girls were opening up in Germany. In 1906 she started at the University of Breslau, although at first she had to audit classes because girls had to apply to the Ministry of Education for a special permit to study at universities. That changed in 1907, and she was able to become an official student.

Hedwig Kohn (back row, on left)possibly withfamily or on a school trip. 1911.

AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, gift of Dr. Wilhelm Tappe, Kohn Photo Collection

Kohn Hedwig D8

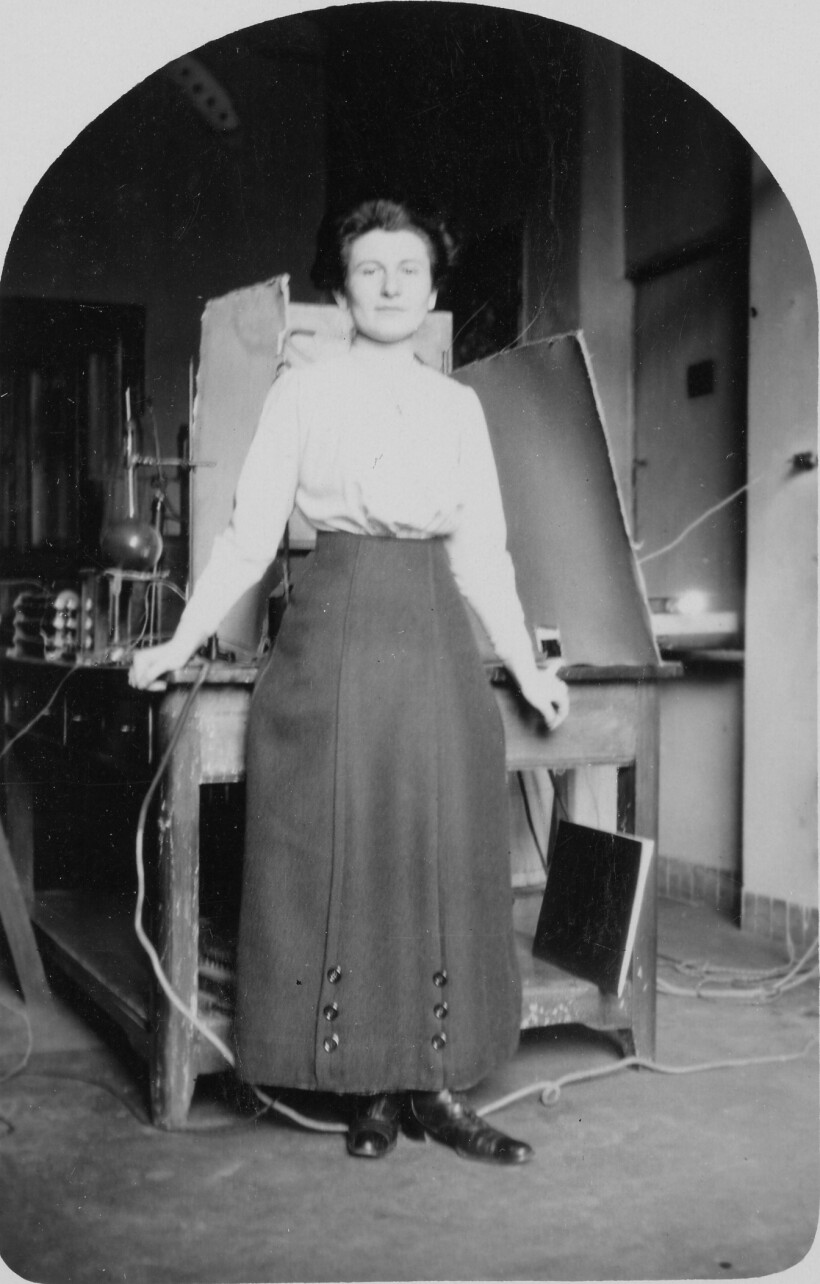

Hedwig Kohn at what was the University of Breslau Physics Institute, Breslau, Germany, and is now the University of Wroclaw, Wroclaw, Poland. 1912.

AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, gift of Dr. Wilhelm Tappe, Kohn Photo Collection.

Kohn Hedwig F2

Hedwig Kohn specialized in spectroscopy, observing and interpreting electromagnetic spectra. During her time at the University of Breslau she worked on block body radiation and eventually wrote her doctoral thesis in 1913. Kohn studied for her doctorate under Otto Lummer and later worked as his assistant, a particular honor for a young woman during an era when many scientists didn’t want to have women students at all, much less pay them to do research. However, though she conducted most of the experiments for an expanded edition of one of Lummer’s textbooks, she was not listed as an author or contributor; rather. she was merely thanked in the acknowledgments. In Sisters in Science, Olivia Campbell writes, “this is just one example of how the extent of women’s contributions is erased from the historical record. Still, it wasn’t unusual for the time, so Hedwig likely never expected coauthorship credit.”

(Standing L-R):Hedwig Kohn, Conrad, Schubert, H.Senftleben, Brieger, Thilo, Benedict and (seated) O. Lummeron the occasion ofOtto Lummer’s birthday.1915.

AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, gift of Dr. Wilhelm Tappe, Kohn Photo Collection

Kohn Hedwig D15

During World War I, Kohn was working overtime while many of the men were at the front. However, that experience didn’t make her path towards habilitation (full qualifications to teach at a university in Germany) any easier or faster. She first attempted this certification, almost like a second dissertation, in 1919 but was refused because she was a woman. Thus far the only woman in Germany to obtain habilitation was Emmy Noether, who was awarded her certification in 1919 after years of trial and tribulation. Another opportunity arose when Otto Lummer asked her to contribute three chapters to a physics textbook he was writing with a focus on radiant energy. Despite the abrupt death of Lummer in 1925, the massive textbook was published in 1929, and her substantial contributions led to her successful habilitation in 1930. However, she was still considered an unsalaried lecturer rather than a full professor.

Hedwig Kohn sitting outdoors.Gräfenberg, [Germany,] 1929.

AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, gift of Dr. Wilhelm Tappe, Kohn Photo Collection

Kohn Hedwig A7

Hedwig Kohn’s success was not long lived, as the Nazis came to power in 1933 and barred Jews from government positions. She spent years working what jobs were allowed to Jewish women, avoiding the violence of Nazi power, and trying to get out of Germany. The United States made immigration difficult because it required professors to have spent the previous two years teaching at a university. Many German women were unable to qualify because of institutional sexism that prevented them from being hired at universities or even from applying for or obtaining habilitation.

The Gestapo told Kohn that if she didn’t leave Germany by June 1940, she would be deported to a camp in Poland. Many of her peers like Rudolf Ladenburg, Lise Meitner, and Hertha Sponer (Meitner and Sponer are also profiled in Sisters in Science and later in this post) worked tirelessly to help her and after several false starts she secured a travel visa to Sweden where she could await a longer-term situation in the United Sates. Finally, in 1941, she was able to immigrate to the US where she worked at the Women’s College of the University of North Carolina. She moved to teaching at Wellesley College in Massachusetts in 1942 and was appointed full professor in 1948. She continued to work on spectroscopy throughout this time.

Portrait of HedwigKohntaken in her office at Wellesley College,Wellesley, Massachusetts. 1947.

AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, gift of Dr. Wilhelm Tappe, Kohn Photo Collection

Kohn Hedwig A5

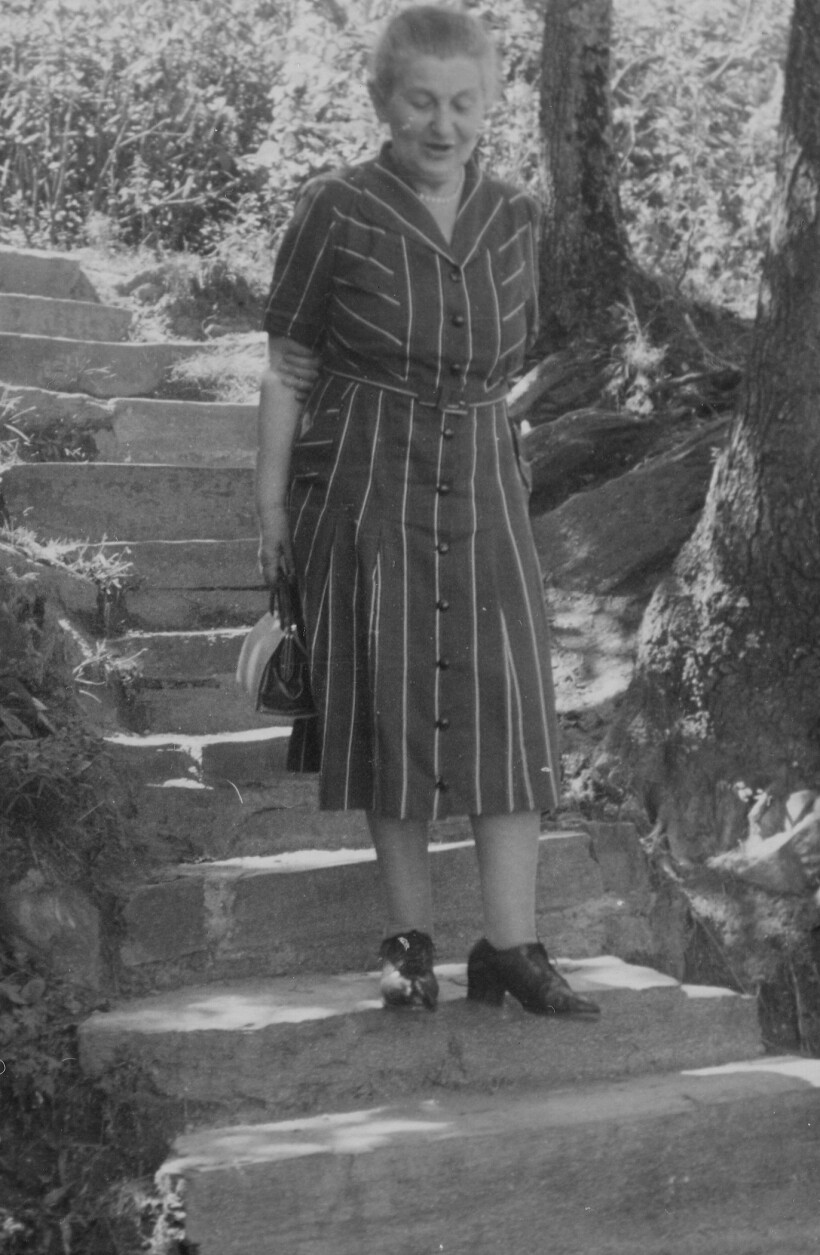

Hedwig Kohn walking outdoors in Durham, North Carolina. 1954.

AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, gift of Dr. Wilhelm Tappe, Kohn Photo Collection

Kohn Hedwig B2

Hertha Sponer-Franck

Hertha Sponer was born in Germany in 1895. She attended the University of Tübingen before moving to the University of Göttingen to study theoretical physics. She rushed to finish her degree before an infamously misogynist professor could take over as her adviser, and so she received her PhD in 1920. Hertha was soon hired by James Franck (known for being more open to working with women scientists than some of his colleagues) as an unpaid unofficial assistant at his lab at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry (KWI-PC), where they collaborated on research in spectroscopy. Berlin, however, was becoming an unwelcome place for Franck, who was Jewish, so he soon relocated his lab and his family to the University of Göttingen and as his loyal assistant, Hertha came too. Though she left Berlin behind, she made many important connections there, including with Lise Meitner.

Hertha Sponer-Franckworkingwith equipment in a laboratory.

AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Lisa Lisco, Gift of JostLemmerich

Sponer Hertha F3

At Göttingen, Sponer was finally able to obtain a paid position and begin her pursuit of habilitation so she could teach at the university. Unfortunately, her old antagonist from her student days was in the way; Robert Pohl was opposed to women working in science. James Franck helped persuade Pohl to allow Hertha to pursue habilitation, but only if her employment was tied to Franck’s — a compromise that would soon have serious implications for Hertha.

Students at the Göttingen Institute feigning frustration or boredom. (Left to right): possibly Friedrich Kirchstein, possibly Paul Emil Flechsig, Reinhold Mannkopf, Hertha Sponer, Heinrich Gerhard Kuhn. Photograph is from Hertha Sponer’s Göttingen album.

AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Franck Collection

Gottingen Institute D2

Hertha Sponer won her habilitation in 1925, making her the second woman to achieve it in her field, after Lise Meitner. That same year, James Franck won a Nobel Prize in Physics for his collaboration with Gustav Hertz on research about “the laws governing the impact of an electron upon an atom.” Soon after, Sponer travelled to America to work at the University of California, Berkeley, on a Rockefeller Foundation grant. While there she published a solo paper in Nature on her spectroscopy research.

Group photograph taken at the Göttingen Institute. Row 1: Hermann Heinrich Maier-Liebnitz, Possibly Oeser, Werner A. Kroebel, Unidentified, Unidentified, G. W. Rathenau, Unidentified, Unidentified, Unidentified Row 2: Lothmar, Arthur Von Hippel, Hans Jaffe, Unidentified, Bernhard Duhn, Hans Stille, Eugene Rabinowitch, H. Kuhn, Hertha Sponer (far right). Photograph is from Hertha Sponer’s Göttingen album.

AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Franck Collection

Gottingen Institute E2

In 1933 the Nazis came to power in Germany and almost immediately passed laws restricting the rights of German Jews. In April of 1933, one month after the election, James Franck publicly resigned as a message of support to other Jews, even though he was exempt from the new restrictions because he was a veteran of WWI. His resignation was big news in Germany and garnered respect and outrage from all corners, though he was famous enough that he could be assured of finding a job almost anywhere (outside Germany). He left Germany in November, hopping around the world until he landed in the US in 1935, where he continued to bounce around to different institutions. Though Franck was safe, Sponer’s job was now in danger. Though she wasn’t Jewish, with the loss of her protector and mentor, being a woman was enough to immediately endanger her position. She was fired by Pohl in December 1933, though she was allowed to continue teaching until the end of the term in October 1934. However, only her assistant position was paid; her lecturing was totally unpaid and she had no other way to support herself. Unwilling to face a demotion to teaching high school, Hertha began to look for a way out of Germany.

Hertha Sponer-Franck’s nitrogen apparatus.

AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Franck Collection

Sponer Hertha F1

Hertha Sponer began to hunt for jobs outside Germany, with the help and support of James Franck. Her connections in America from her fellowship paid off, and she was offered a position at Duke University. However, they still needed to find a way to fund the position. Though she had the support of the head of the physics department, Robert Millikan (who was not even employed at Duke) wrote a letter to the President of the University against her hiring and the hiring of women physicists in general. While waiting for news about Duke, she was offered a temporary funded position at the University of Oslo to begin in 1934. She jumped at the chance, while still keeping her dreams of Duke alive. In 1936 her hopes were finally answered, and she started her position at Duke right around the same time Franck moved to Baltimore to work at Johns Hopkins. She stayed in touch with Franck throughout the 1930s and WWII, even comforting him when his wife died in 1942. In 1946, when he was working in Chicago and she in North Carolina, they got married and continued to work at their respective institutions, only able to live as a married couple during school breaks. Franck died in 1964; Sponer-Franck stayed in her position at Duke until her death in 1968.

Portrait of Hertha Sponer-Franck.

AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Lisa Lisco, Gift of Jost Lemmerich

Sponer Hertha A1

Lise Meitner

Lise Meitner was born in Vienna, Austria, in 1878 to Jewish parents, though she converted to Christianity in 1908. When she graduated high school in 1892, women were still not allowed into Austrian universities. In 1897 the law was changed to allow women into university after passing an entrance exam. Meitner took private physics lessons until she passed her exams in 1901. She studied at the University of Vienna, eventually earning her PhD in 1906. Wanting to study from Max Planck, Meitner moved to Berlin to study at the Friedrich Wilhelm University (later the University of Berlin) in 1907. However, women were still not welcome at German universities, and she was only allowed to audit Planck’s classes.

While studying under Planck, she began her long-term collaboration with Otto Hahn to study radioactivity. She was allowed to join Hahn’s lab only on two conditions: 1) that she never enter the chemistry departments where all the men worked and 2) that she confine her experiments to a woodworking shop in the basement that had been converted into a laboratory.

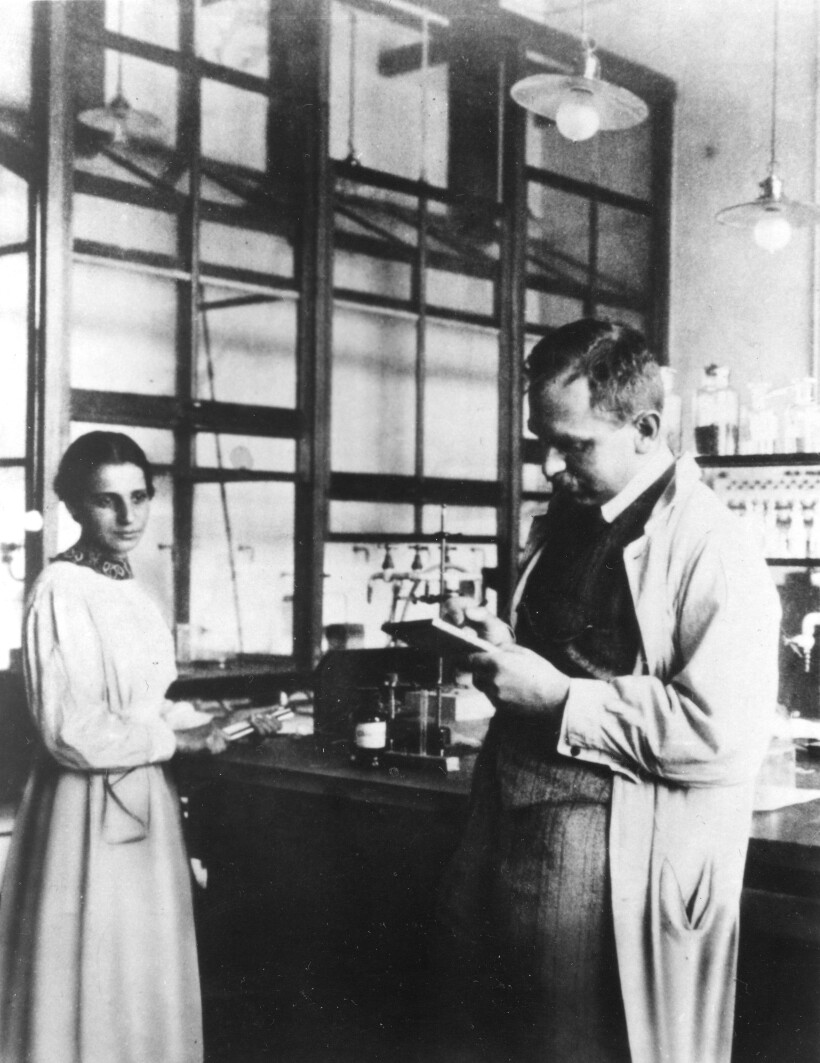

Lise Meitner and Otto Hahn working with equipment in their laboratory at the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institute (KWI) in Dahlem, Berlin, Germany.

Archives of the Max Planck Society, courtesy of AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives

Meitner Lise C2

Lise Meitner and Otto Hahn began a very fruitful collaboration. They authored 9 papers together in 1908 and 1909 alone. In 1912, they both moved to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry (KWI-C) in Berlin. When Max Planck offered her a job as his assistant grading student papers, it was her first paid position. Hahn was appointed a professor, but Lise Meitner was offered no such position, having to essentially volunteer her labor. Hahn and Meitner quickly got to work building their new lab, with strict cleanliness policies to prevent the build-up of residual background radioactive contamination, which allowed them to study very weak radioactivity. Eventually, Meitner was made an associate professor and granted a salary at the KWI-C, though it was less than Hahn’s.

Danish physicist Niels Bohr at a “Bonzenfreie Kolloquium” (which translates to “Colloquium Without Bigwigs”) organized for him by Lise Meitner in Dahlem near Berlin, Germany. Left to right: Otto Stern, Wilhelm Lenz, James Franck, Rudolph Ladenburg, Paul Knipping, Niels Bohr, Ernst Wagner, Otto von Baeyer, Otto Hahn, George de Hevesy, Lise Meitner (only woman), Wilhelm Westphal, Hans Geiger, Gustav Hertz and Peter Pringsheim.

Prof. Wilhelm Westfall, courtesy of AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives

Stern Otto E5

During World War I, Hahn served in the army while Meitner worked as an X-ray nurse-technician. Meitner returned to the KWI-C in late 1916, and early in 1917 she was appointed as the head of her own radiation physics department, which came with a hefty raise. Working with pitchblende (also known as uraninite, which Marie Curie used to refine radium), Meitner isolated, named, and explained the properties of the new element protactinium. She was granted habilitation in 1922, becoming the first woman in physics to do so; later, she built on that success to became Germany’s first woman full professor.

Group sitting on the steps of a building, includingLise Meitner (only woman)and Otto Hahn (seated to the left of Meitner).

AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives

Hahn Otto E1

Lucy Mensing (second from left), Lise Meitner (center), Wilhelm Schütz (right, whom Mensing would eventually marry), and unidentified others on a mountain hike in theÖtztalin the Austrian alps in 1934.

AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Mensing Collection, Gift of Dr. Dorothea Roloff

PH2022-2924_002_d

Meitner’s rise to acclaim was interrupted by the Nazis’ rise to power. She lost her positions in 1935, and in 1938, her Austrian citizenship. During the summer of 1938, Meitner dramatically fled Berlin to a position in Sweden (where she’d previously spent some time lecturing on radioactivity and learning about spectroscopy), via the Netherlands and Denmark. She couldn’t pack more than a couple of suitcases for fear that she’d be discovered. Dirk Coster (a Dutch physicist who traveled to Berlin to help convince Meitner that she had to flee) helped sneak her out of the country and Otto Hahn gave her a diamond ring in case of an emergency.

During this period, she also conducted the most famous work of her career with Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassman. Corresponding by phone, letter, and secret meetings, they collaborated on research that would change the world. Hahn wrote to Meitner of their discovery that radium isotopes act like barium after they bombarded uranium with neutrons. In Sisters in Science, Campbell quotes Hahn’s correspondence: “perhaps you can come up with some sort of fantastic explanation. We know ourselves that it can’t actually burst apart into [Barium].” Meitner discussed Hahn’s letter in Sweden with her nephew Otto Robert Frisch (a physicist who worked with Niels Bohr) and realized the significance of this discovery. They continued to collaborate after their visit, proving that Hahn and Strassman had split the atom. Meanwhile, Hahn and Strassman rushed to publish their initial findings. Meitner and Frisch followed by publishing their conclusions and coining the term “fission.”

Otto Hahn and Lise Meitner at the Hahn-Meitner Institute in Berlin, Germany.

AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives

Hahn Otto C3

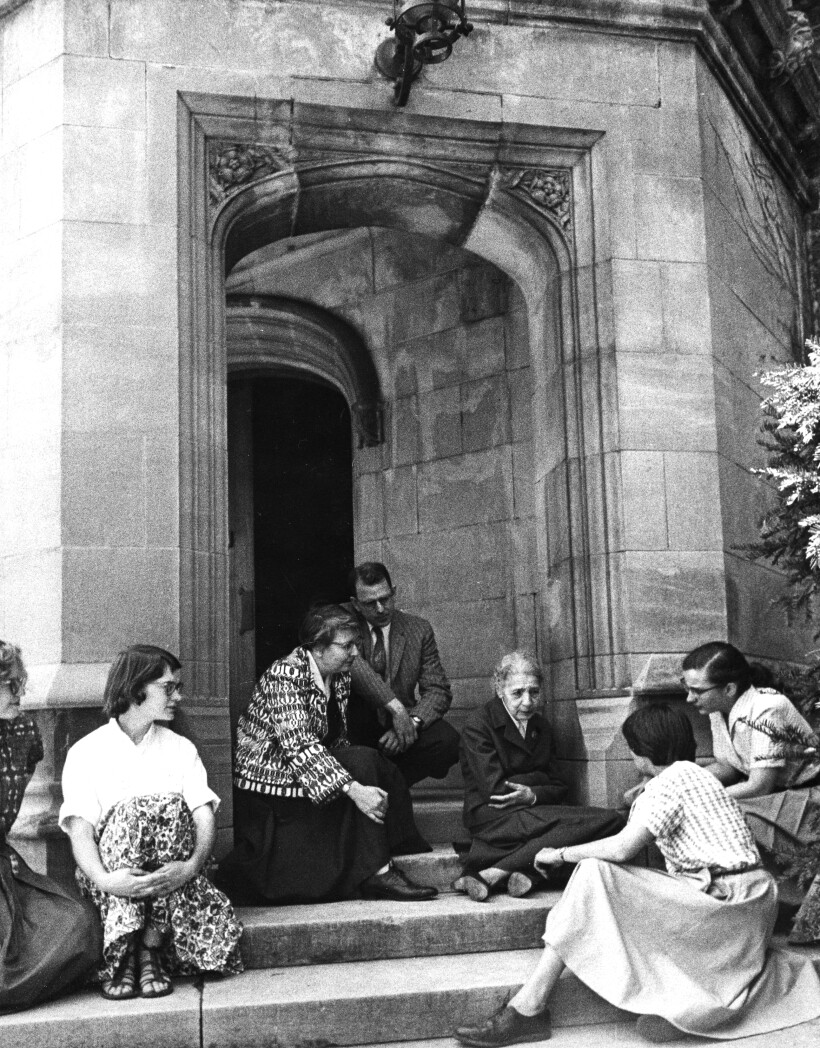

Lise Meitner spent World War II in Sweden, continuing to work and helping fellow physicists leave Germany, including Hedwig Kohn. Despite most of her colleagues, including her nephew, Otto Robert Frisch, going off to work for the Manhattan Project, she declined to ever work on an atomic bomb on principle. In 1944, Otto Hahn won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work on nuclear fission. Despite being nominated numerous times throughout her life (both before and after her nuclear fission discovery), Lise Meitner never received the same acknowledgment of her contributions, nor did Strassman. She became a Swedish citizen in 1949, while still being able to keep her Austrian citizenship, and moved to the UK in 1960 after her retirement to be with her relatives. In 1959 she visited Bryn Mawr College to give several lectures, and out of those lectures she published “The Status of Women in the Professions

“Looking back, I have the impression that the problems of professional women in general, and particularly of academic women, have found fairly satisfactory solutions in the last 80 or 100 years. Not all that can be desired has been achieved. In principle, nearly all male professions have become accessible to women; in practice, things often look different.”

She writes that despite many examples of exceptional accomplishments by women, those are not indicative of unfettered access to the higher levels of industry and academia. She specifically notes the issue of married women trying to maintain professions while trying to balance housework, childcare, and professional duties. “Undoubtedly, women can see no ideal solution to their problem: profession and family. But for what human problems do ideal solutions exist?” She concludes, “we can no longer doubt the value and indeed necessity of woman’s intellectual education, for herself, for the family, and for mankind.”

(Left to right): First two women unidentified, Agnes Michels, John R. Pruett, Lise Meitner, Professor Rosalie Hoyt, AB1936and PhD 1945 (with back to camera),and Sue Jones Swisher, class of 1960, at Bryn Mawr College, Pennsylvania. April 1959.

Photo by Robert Davis, courtesy of AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Physics Today Collection

Meitner Lise D1

Lise Meitner (center) with students at Bryn Mawr College, Pennsylvania. Left to right: Unidentified woman, Agnes Michels, Lise Meitner, Sue Jones Swisher, class of 1960, and Danna Pearson McDonough, class of 1960.

Photo by Heka Davis, courtesy of AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Physics Today Collection

Meitner Lise D5

Lise Meitner died in 1968 in Cambridge. Before her death she was nominated

Portrait of Lise Meitner at Bryn Mawr College.

AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Gift of JostLemmerich

Meitner Lise B5

Hildegard Stücklen

Hildegard Stücklen was born in Berlin in 1891. She obtained her PhD from the University of Göttingen in 1919. She moved to Zurich to work and taught at the University of Zurich while doing her spectroscopy research. She moved between various labs at the University while doing her research and began to publish her findings. She was asked to contribute to the 1926 Das Handbuch der Physik; she wrote three chapters while most other contributors only wrote one. Despite her work as a researcher, lecturer, and author, she still had to rely on her translation work to make a living.

Hildegard Stücklen completed her habilitation in 1931 and spent a year in the US at a fellowship at Mount Holyoke College. After the Nazis came to power, immigrants started flooding into Switzerland; as a result, Switzerland restricted immigration and her assistant position at the university was cut, although with the lobbying of chemist Jeanne Eder-Schwyzer, the president of the Swiss Association of University Women, she was permitted to keep lecturing.

With the help of several organizations and fellowship funds, she was allowed to emigrate to the US in 1934 to teach at Mount Holyoke College, which she did until 1939. While at Mount Holyoke she collaborated with Emma Carr (an old friend she’d worked with several times before), Mary Sherrill, and Lucy Pickett. They applied for and received a National Research Council (NRC) grant for their spectroscopy research; Emma Carr and Hildegard Stücklen published seven join papers during this time. However, she was paid a measly salary and only on short-term contracts. When Rogers Rusk was made the head of the physics department he wanted to hire more men and only Emma Carr’s advocacy kept her in in a joint chemistry and physics role. With the advice and assistance of Hertha Sponer and James Franck from afar, Hildegard took a leave of absence from Mount Holyoke to job hunt in California. Despite Millikan’s infamous resistance to women scientists, she spent a year teaching at Caltech from 1941 to 1942. Then, finally, a more permanent offer came from Sweet Briar College in Virginia, where she taught from 1943 to 1956. Though she had little time for research, she spent her breaks researching with Hertha Sponer at Duke. Hildegard moved back to Germany in 1960 for her retirement, she died there in 1963.

(L-R): Walter Michels, Hildegard Stücklen, and Jane Dewey (hidden) in an unknown location,possibly in Michigan.

Photograph by Samuel Goudsmit, courtesy of AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Goudsmit Collection

Michels Walter C2

This is the only photograph we have of Hildegard Stücklen and we don’t have a date or a location to go along with it. There are very few photos of Stücklen available online, perhaps she just didn’t take as many photographs as the other women, or they just didn’t get preserved. Or perhaps she had to move around between too many places to save as many mementos as the other women, we may never know.

Though Meitner, Kohn, Sponer, and Stücklen are hardly household names for most people, their contributions (and so many other women’s) to the history of the physical sciences deserve to be documented, both by archives like ours and by researchers and authors like Olivia Campbell. We like to say that our photo archive puts a face to physics, and though this is just a taste of what you can discover about the lives of these four fascinating women in Sisters in Science, we hope their faces are more fixed to your memory now after viewing these photos. And if you have any photos of women in the physical sciences, please consider sharing them with us