Author Jeffrey Orens.

Cathy Rosselli

Author Jeffrey Orens.

Cathy Rosselli

We are delighted to welcome author Jeffrey Orens to the blog! Orens is a former chemical engineer and business executive with Solvay Chemical who has written for several history publications. His first book is entitled The Soul of Genius: Marie Curie, Albert Einstein, and the Meeting that Changed the Course of Science

Please tell us a bit about the book. What drew you to the Solvay Conference and the meeting between Albert Einstein and Marie Curie?

My initial attraction to the Solvay Conference came in the form of a picture. It’s often referred to as “The Most Intelligent Picture Ever Taken,” a shot of the participants of the 1927 Fifth Solvay Conference on Physics. Seventeen of the twenty-nine participants at the conference were, or would eventually become, Nobel Prize winners in physics or chemistry.

I had recently become employed by Solvay Chemical via a merger with my previous company, Cytec Industries. Many Solvay offices have a life-sized image of this picture gracing a wall, a reminder of the heritage of the company and its dedication to science. Albert Einstein and Marie Curie are clearly seen in the first of three rows of scientists in the picture, impassively staring out at the observers along with the others in the black and white photo. The picture sparked a desire to learn more about these individuals and what brought them together.

“The Most Intelligent Picture Ever Taken.” The 1927 Fifth Solvay Conference on Physics.

Photograph by Benjamin Couprie, Institut International de Physique Solvay, courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives. Einstein Albert E3.

Once I began to delve deeper, it became apparent that there was much more to tell, about the people, their lives both personally and professionally, as well as the need for the conference in the first place. It turns out the First Solvay Conference on Physics, which was the place where Curie and Einstein initially got to know each other, was convened to discuss the collision of the classic Newtonian physics of gravity and laws of motion with the newly-developing discoveries of the subatomic universe and its differences from classical understandings. Nine of the twenty-four attendees were to become Nobel laureates, gathered by Ernest Solvay to debate the inconsistencies between classical physics and quantum theory.

1911 Solvay Conference. Marie Curie is seated in the front row, second from the right, and Albert Einstein is standing behind, second from the right, with Paul Langevin next to him on the far right. Marcel Brillouin, whose papers were an important source for the book, is in the seated row, second from the left.

Solvay Heritage Collection.

But the conference also came at a time of great personal upheaval for Marie Curie and professional recognition for Einstein. At the conference, Curie was almost simultaneously notified of her winning a second Nobel Prize as well as shocked to learn that her covert affair with the French scientist Paul Langevin, another conference attendee, was exposed, to devastating effect, in the French press. Einstein’s presence at the meeting amounted to his “debutante ball” that displayed his genius to a larger portion of the scientific community and helped launch his career from an obscure university professor in Prague to become world-renowned as the father of relativity.

What is your background? How did you develop an interest in the history of science?

I’m a chemical engineer by training, with an MBA picked up along the way. I spent forty years in the chemical industry with Union Carbide, Dow, Air Products and Chemicals, and Solvay, mostly as a business executive running global commodity and specialty chemicals businesses. I learned about Ernest Solvay, with his unique approach to making the chemical additive sodium carbonate for glass, soap and textile manufacture, when I came to work for Solvay Chemicals. I became aware not only of Solvay’s ground-breaking approach to turning a simple laboratory process into scalable industrial production, inventing the profession of chemical engineering in the bargain, but of his later years as a scientific philanthropist who sponsored the unique forums bearing his name. My interest in all of this was historical as well as scientific, both areas that intrigued me from a young age.

In the introduction, you point out that the idea behind the Solvay conferences was a relatively novel concept at the time. Can you tell us more about this?

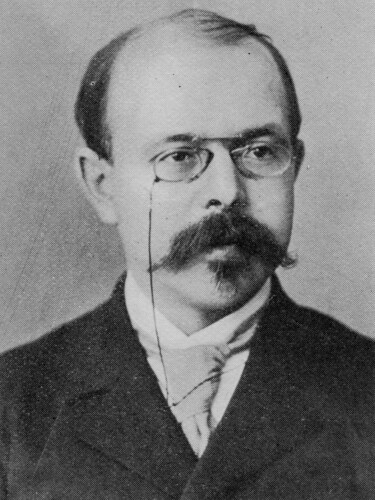

Portrait of Walther Nernst.

Rijksmuseum Voor de Geschiedenis der Natuurwetenschappen, courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives. Nernst Walther A3.

The conference was conceived by German scientist Walther Nernst and financially sponsored by Ernest Solvay. In the opening decade of the twentieth century, the classic theory of light as a wave of energy was being challenged by the thought that light could be composed of discrete particles of energy, called quanta. The German Max Planck had first suggested the idea in 1900, based on his investigation of black body radiation. By 1905, Einstein developed a paper published on the energy quanta as it explained the photoelectric effect, essentially supporting Planck’s hypothesis in the process. Nernst wanted to bring together a small group of elite scientists to debate these concepts. In doing so, he knew it would help validate some of his own experimental work and help legitimize it for future professional recognition, perhaps even deserving of the Nobel Prize itself.

He approached Solvay about sponsoring a gathering of a few premier physicists who could discuss, debate, and decide what to do next related to the energy quanta. Up to this point, scientific conferences were rather large affairs, bringing hundreds of scientists together to give formal papers on a wide variety of topics, with little if any time for discussion on the presentations given or potential next steps to take in experimentation. Nernst’s idea involved selecting a hand-picked list of attendees, asking a number of them to write papers on specific topics of interest for distribution to the invitees for review prior to their presentation at the meeting, and then debating the issues after presentation. It was all quite out of the ordinary, its novelty immediately appealing to those invited to be part of the session.

Nernst and Solvay assembled a list of the leading European scientists from France, Germany, England and a few other countries to attend the gathering. Solvay insisted that Hendrik Lorentz, the incomparable Dutch physicist whose genius included his multilingual abilities, be the meeting’s facilitator. Finally, to further entice the invitees, Solvay offered to pay one thousand francs apiece to cover travel, lodging and meals for the five day meeting. Basically, it all amounted to an offer few could refuse. The meeting was considered a success, if not in solving the mysteries of the energy quanta versus classical physics, then in at least laying bare the discontinuities between the two theories and developing plans on further experimentation to solve them. Within months, the conference led to Solvay’s establishment of an International Institute of Physics in Brussels for selection and financial support of scientific projects that were deemed essential for further research, all sponsored by Solvay’s financial largesse.

As well, Einstein’s unique brilliance was displayed before this illustrious group, launching his meteoric rise in the physics community over the ensuing decade. His friendship with Marie Curie was also established at this time, a bond that was relied on by both in the years ahead.

Albert Einstein (left) and Marie Curie (right) conversing by a lake in 1929.

AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives. Einstein Albert C74

How did you go about your research for the book? What was your starting point? Were there any particular challenges to finding information and/or getting access to research materials?

When I began my research, I initially assembled biographies of both Curie and Einstein. Multiple volumes have been written on each over the years; these presented a significant starting point in which to immerse myself. As well, my former connection with the Solvay company helped me investigate the life of Ernest Solvay through contact with an individual who is specifically involved in company history and archives – he provided me with direction on where I might find information on both the man and his activities, professionally and personally. Significant primary and secondary source research on all the major topics took place in various libraries in the New York City area as well as on the Internet.

The collected papers of both Curie and Einstein were primary sources that needed investigation. Einstein’s papers

You describe the Léon Brillouin papers

Portrait of Paul Langevin.

AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives. Langevin Paul A1.

At the time of the 1911 Solvay Conference, Marie Curie and fellow French scientist Paul Langevin were having an affair, one that was not publicly known until Langevin’s wife decided to expose the details to the press as the conference came to a close. Curie’s husband Pierre had been dead for over five years, killed in a tragic accident, and Langevin’s marriage had been foundering for even longer. Paul had been a scientific protégé of Pierre’s before his death, so the families knew each other. In the years since Pierre had died, Paul’s marriage continued to deteriorate, and Marie became closer to Paul. As a married man with four children, Marie became the “hidden-in-plain-sight” mistress of Paul, whose wife was becoming more uncomfortable with the situation while Marie implored Paul to leave his wife and family for a life with her. Things finally culminated with Paul’s wife discovering love letters written between the two and deciding to publish some of them in the newspapers in an attempt to shame the two into ending the relationship.

In researching this episode, I stumbled across an Internet thread that led me to a finding aid for the collected papers of physicist Marcel Brillouin, Léon’s father as well as a French scientific peer of Curie’s and Langevin’s who also attended the 1911 Solvay Conference. The papers were housed within his son’s collection at the NBL&A. The aid stated that notes and letters about the affair between Marie Curie and Paul Langevin were part of Marcel’s papers, but nothing more. When I contacted the NBL&A about this information, they did a bit of investigating and told me that indeed, scores of pages existed in the files, hand-written in French, in both journal form and as a few letters. The library staff was more than happy to digitally scan and send me copies of this information. The next step was to translate all of this into English to determine if any of it had value for my narrative. Fortunately, I had friends available who could help me in this regard, and over the course of the next few months what emerged was an amazing, first-hand account of the affair between Curie and Langevin.

From the Papers of Léon Brillouin, 1877-1972 at the Niels Bohr Library & Archives. A page from Box 1, Folder 6, containing “Correspondence between M. Brillouin, J. Perrin and H. A. Lorentz regarding Langevin-Curie Affair, 1911.” Reads: confidential letters, Subject: Langevin Curie, by Misters Brillouin, Perrin, Lorenz, 1911.

A journal page from the Papers of Léon Brillouin, 1877-1972 at the Niels Bohr Library & Archives. A page from Box 1, Folder 6, containing “Correspondence between M. Brillouin, J. Perrin and H. A. Lorentz regarding Langevin-Curie Affair, 1911.”

Marcel and his wife had been good friends with the Langevins, and the account from Marcel’s papers was mainly derived from Langevin’s wife relaying her thoughts, suspicions, and finally the contents of some of the love letters themselves to Marcel’s wife. This appears to be the first time this source has ever been used to describe the Curie/Langevin affair. It varies from the widely-employed accounts conveyed by friends of Marie, who were much more sympathetic to her cause. As well, it all was told by Marcel, a conservative Frenchman who was much more disapproving of the whole situation than were Curie’s friends. The incident is covered in a chapter in my book, guided by the notes and letters of Marcel Brillouin, courtesy of the NBL&A.

Are there other libraries/archives that were important in your research for the book?

In addition to the NBL&A, the Rare Book and Manuscripts Library of the Butler Library, Columbia University in New York City provided access to papers written by Marie Curie about her initial trip to America in 1921. These papers are part of the Marie Mattingly Meloney Collection on Marie Curie, Meloney being an influential women’s magazine editor who sponsored the trip. The online archives of the Senator John Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania provided digitized versions of information related to Curie’s American visit. The online archives of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia provided digital views of documents pertaining to Isaac Newton.

Are there any conclusions that you hope readers of the book might draw about Marie Curie’s struggles in the aftermath of the scandal?

Portrait of Marie Curie, February 1914.

A. M. Chesney Medical Archives, Johns Hopkins Medical Institute, courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives. Curie Marie A14

Curie is depicted in the narrative as innately of superior intelligence, fiercely devoted to her work, and dedicated to a life of science. That she ultimately overcame almost every obstacle placed in her path to become the most recognized woman scientist of the twentieth century is a testament to her brilliance, iron will and diligent research. After her affair with Paul Langevin was publicized, her reputation was in tatters in France. But, with the beginnings of World War I, she devised the use of compact, mobile X-ray equipment to be employed on the front lines to save badly wounded Allied soldiers from death or dismemberment by quickly locating metal bullet and shrapnel fragments for surgical removal. This novel approach generated grateful appreciation from the French public and helped her regain her stature.

Was there anything particularly surprising that you came across in the course of your research for the book?

One thing that took me a bit by surprise was the rather siloed world of those within physics at the turn of the 19th century. There were a relatively small number of physicists worldwide, estimated at slightly over 1000 total, mostly in Europe with a hundred or so each in England, France, and Germany, with smaller populations in countries such as Austria-Hungary, Denmark, and Switzerland. This sheer paucity in numbers had led me to believe that the physics community as a whole would be more tight-knit in its associations and shared understandings. But, as I delved deeper into the nature of the discipline at the time, because of language barriers as well as pronounced nationalistic pride, each country tended to keep shared scientific discussion within the distinct realms of German, French, and English scientific circles. These cultural barriers made it somewhat difficult for a French physicist to follow published German scientific investigations of the day if the French scientist did not know German. Thus, Einstein’s four astounding papers on physics that were published in a German physics journal in 1905 were still relatively unknown to some of the leading European physicists, especially the French, who gathered at the First Solvay Conference in 1911. One of the benefits of the conference was to break down these barriers with intimate discussion of crucial topics like quantum theory, aided by the multi-lingual conference facilitator Lorentz, allowing for clearer understandings of the participants as well as ensuing debate of alternative approaches to solving these mysteries of physics.

Why did you state in the title of your book that this was a “Meeting that Changed the Course of Science?”

Book cover for The Soul of Genius.

Cover Design by Faceout Studio, Amanda Hudson. Cover Imagery from Bridgeman and Shutterstock.

The 1911 First Solvay Conference was indeed unique. As I’ve noted, international meetings of physicists, when they occurred intermittently, involved hundreds of scientists gathering for formal presentation of papers. In contrast, twenty-four geniuses gathered at the Solvay meeting, prepped beforehand with copies of the papers to be presented, and proceeded to discuss and debate the merits of the issues, a forum unlike anything that had come before. This meeting changed the manner in which scientists could address the most pressing issues of the moment, appreciated for its novelty in providing the ability to quickly get to the heart of the each matter being reviewed.

This particular conference was brought about by the importance of quantum theory and the need to reconcile it with classic physics thought. Until this gathering, there existed different understandings about the energy quantum, with some physicists not even aware of the quantum and its impact on existing theory. This meeting forced the select scientific elite at the gathering to confront the quantum theory’s collision with classic physics, sparking a debate that was to rage for the next two decades, and in some aspects even to this day. But one thing was certain: the view of the physical world would never be the same after the conference.

Lastly, and just as importantly, the First Solvay Conference propelled Einstein’s rapid rise to scientific fame, first within the physics community and then worldwide. It provided a platform for him to exhibit his genius for a greater part of the non-Germanic speaking physics world to observe. Shortly after, he moved to Zurich and then Berlin in positions that recognized his brilliance and allowed him to develop his General Theory of Relativity. As well, it was at this conference that Marie Curie and Einstein formed a friendship that was to be supportive and loyal through personal travails and scientific musings (though not sharing in each other’s scientific investigative efforts).

-Q&A organized by Corinne Mona, Assistant Librarian

*For more on the Curie Langevin affair, check out the Center for History of Physics’ web exhibit

Subscribe to Ex Libris Universum

Catch up with the latest from AIP History and the Niels Bohr Library & Archives.

One email per month