International Students in U.S. Physics and Astronomy Graduate Programs: Trends, Visa Risks, and Degree Outcomes

President Trump and his administration aim to change U.S. visa and immigration policy for international students in the next several months. These changes could significantly affect the physical sciences community. This brief report utilizes data from AIP’s core surveys of physics and astronomy departments, students, and recent degree recipients to answer basic questions relevant to proposed changes.

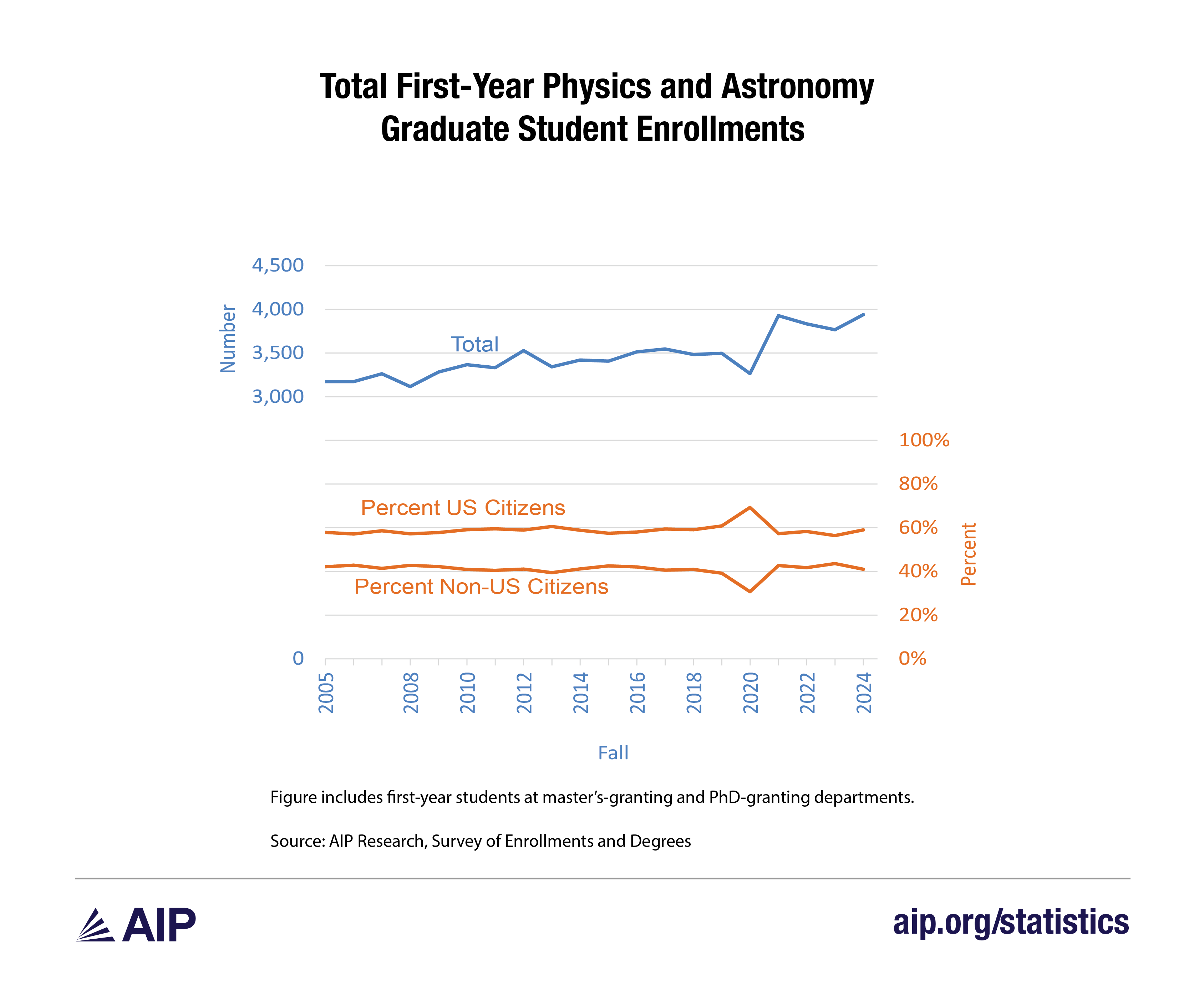

What percentage of first-year physics and astronomy graduate students are international students?

Over the past two decades, first-year enrollments in physics and astronomy graduate programs have increased by approximately 21%. During this period, international students have consistently represented about 42% of first-year enrollments, with the notable exception of fall 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic restricted international travel to the United States (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Virtually all first-year international physics and astronomy graduate students held F-1 or J-1 student visas, with the largest share coming from Asia—predominantly India, China, and Nepal.

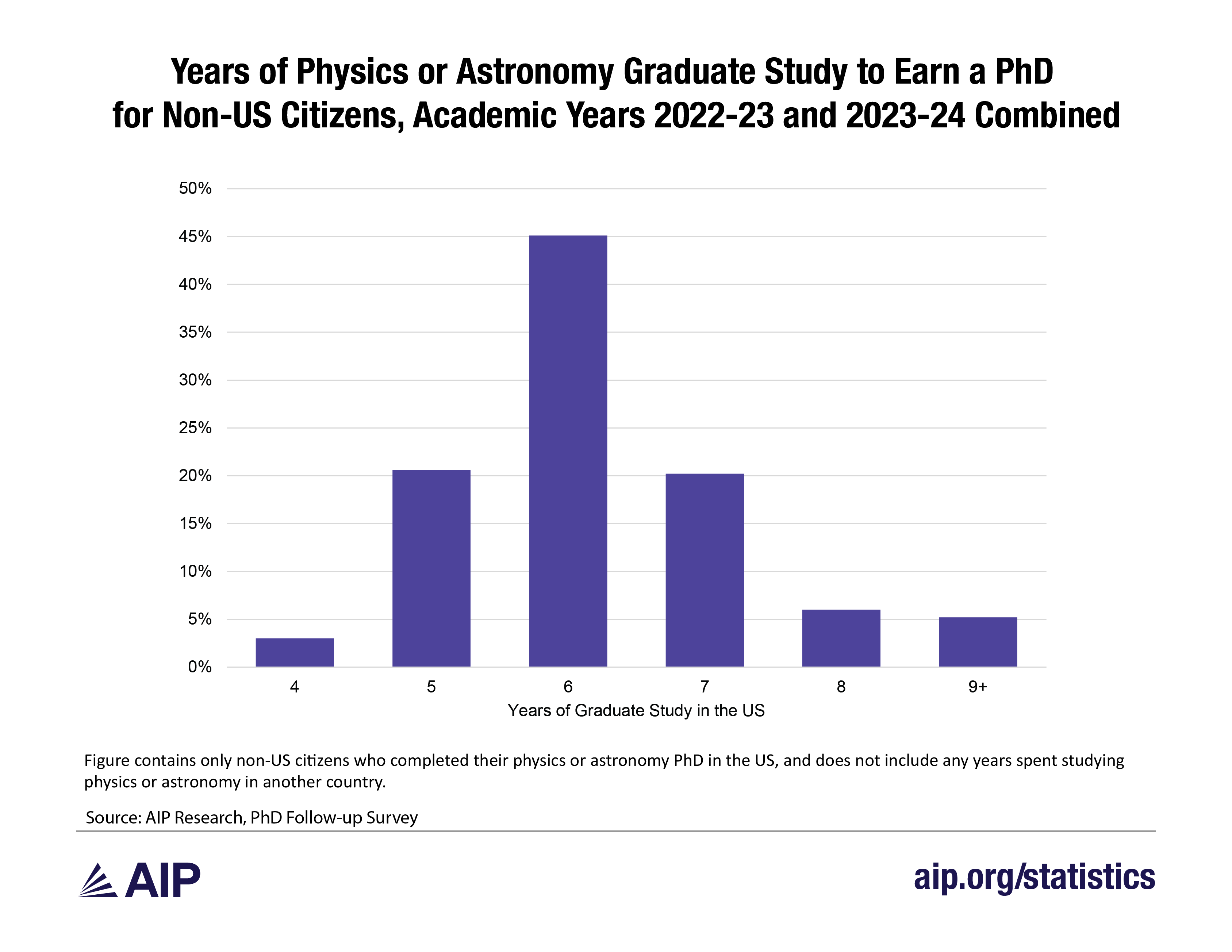

How long does it take for international students to earn a PhD in Physics or Astronomy?

The time international students spend in U.S. graduate physics or astronomy programs to complete their PhD varies somewhat. The median duration is six years, which is the same as for U.S. citizens (Figure 2).

Figure 2

As of this writing, the White House has proposed regulations that would limit most F-1 and J-1 visas to four years (Department of Homeland Security, 2025

Students enrolled in programs exceeding that duration would need to apply for extensions to remain in the United States, and those extensions are not guaranteed. The proposal would also introduce stricter rules for changing majors and shorten the post-graduation grace period. If the visa duration limits were enacted, nearly all international students who take more than four years to complete their degree programs (about 97%) would be affected. This rule remains under consideration and has not yet been finalized.

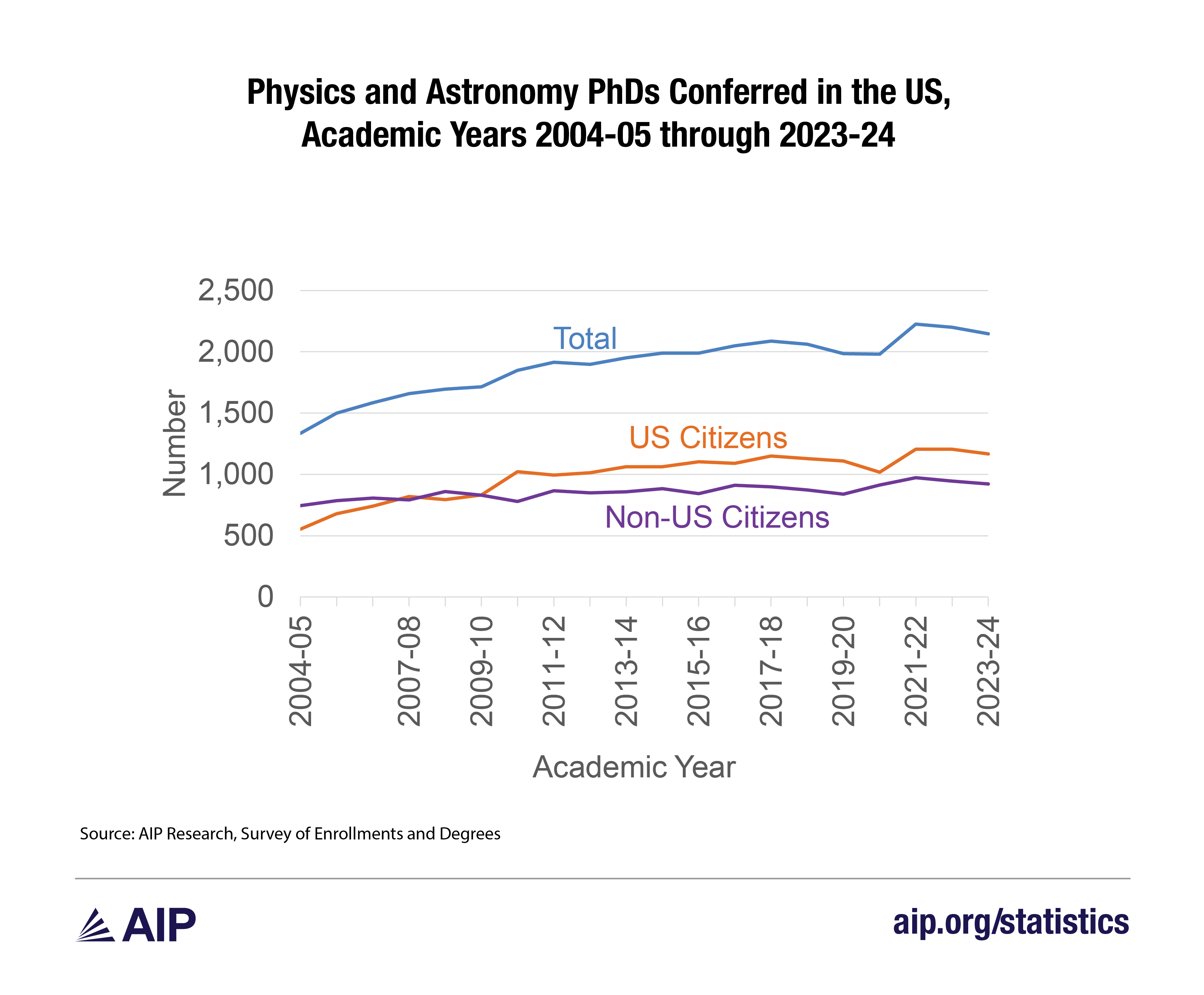

How many international students earn PhDs in physics or astronomy each year?

In the 2023–24 academic year, after an average of six years of graduate study, 2,146 physics and astronomy PhDs were awarded in the United States. This represents a 61% increase compared with the number awarded two decades earlier. Throughout much of this period, non-U.S. citizens have accounted for slightly less than half of the physics and astronomy PhDs awarded (Figure 3). About half of international PhD recipients in physics and astronomy were from China (29%) and India (22%).

Figure 3

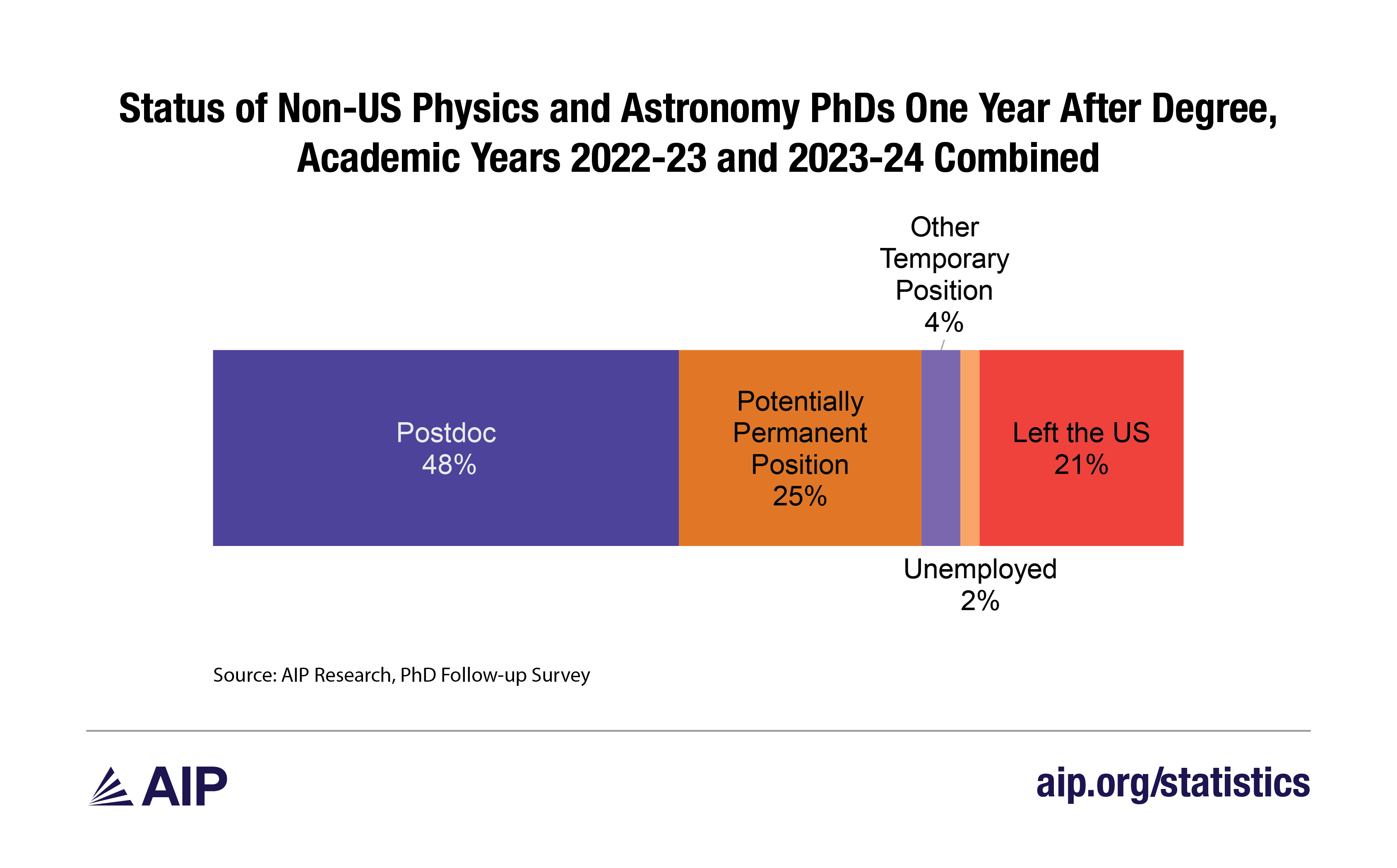

What percentage of international PhD graduates remain in the U.S. after earning their degree?

Over three-quarters of international students earning physics and astronomy PhDs in the 2022–23 and 2023–24 academic years remained in the United States for employment in the year after receiving their degree. Most accepted postdoctoral fellowships or other temporary positions, while nearly all remaining graduates obtained potentially permanent employment (Figure 4).

Figure 4

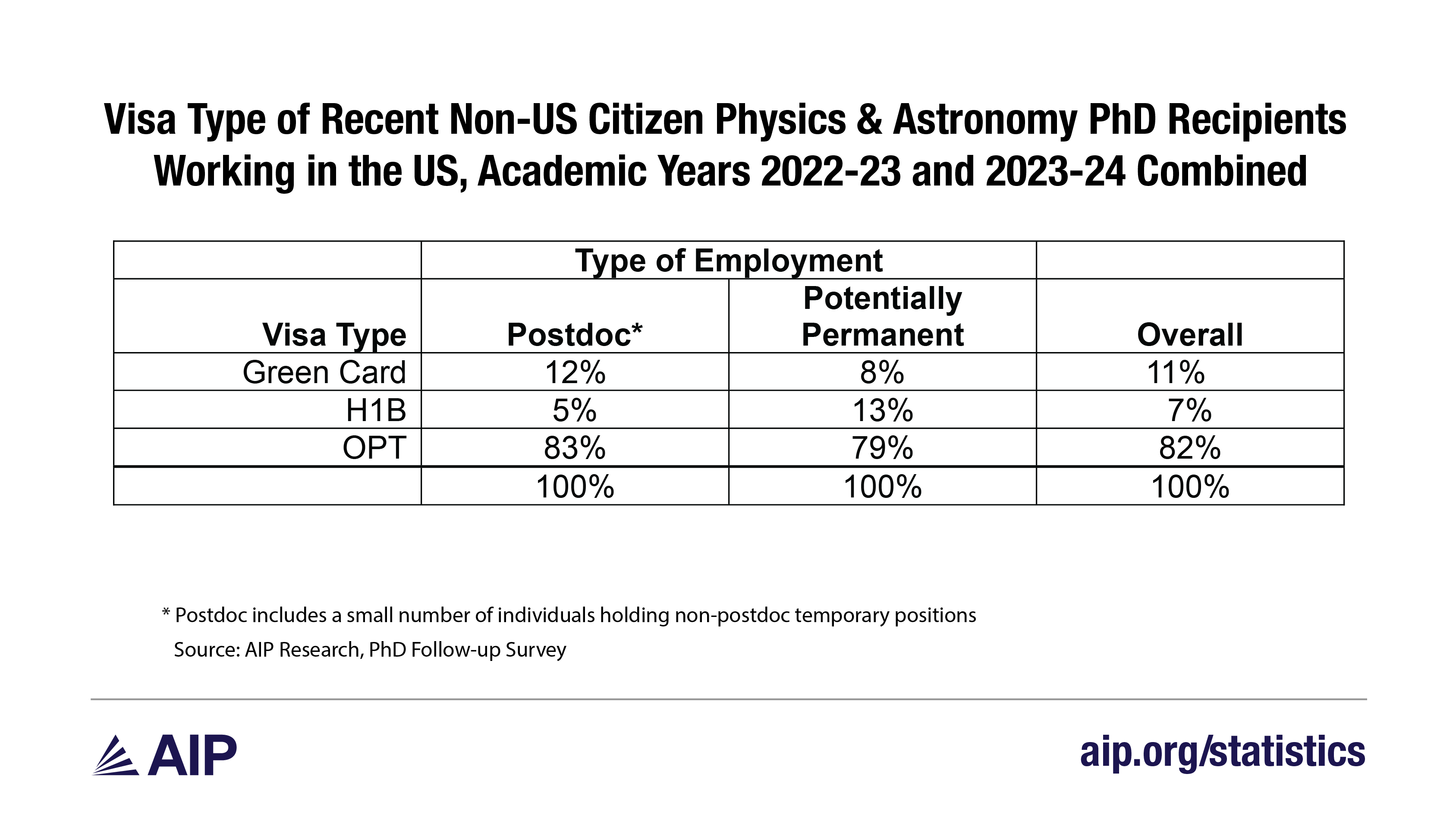

What visa types or statuses do international graduates who remain in the U.S. to work hold?

Among the international physics and astronomy PhD recipients from the academic years 2022-23 and 2023-24 that remained in the United States to work, most (82%) participated in Optional Practical Training (OPT) (Table 1). OPT allows international students to gain work experience in jobs that are directly related to their major area of study (Wilson, 2025

Some U.S. government policymakers have expressed an interest in restricting or eliminating the OPT work authorization. Considering the proportion of new international physics and astronomy PhDs that transition to OPT work authorizations, this potential change would have significant implications for international PhD recipients.

Table 1

References

U.S. Department of Homeland Security. (2025, August 27). Trump Administration proposes new rule to end foreign student visa abuse. https://www.dhs.gov/news/2025/08/27/trump-administration-proposes-new-rule-end-foreign-student-visa-abuse

Wilson, J. H. (2025, May 30). Optional practical training (OPT) for foreign students in the United States (CRS Product No. IF12631). Congressional Research Service. https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IF12631